The Russian public is concerned about NATO expansion but does not think an attack from the West is imminent.

At this week’s NATO summit, enlargement will be a key topic of discussion. Just one day before its start, Turkey announced that it will support Sweden’s application to join the Alliance which—combined with Hungary’s statement that it will not be the last to ratify the bid—clears the country’s path to membership. And Ukraine and nine Eastern European states hope the alliance will offer Kyiv a clear pathway to membership, making good on a 15-year-old pledge that Ukraine has an “open door” to joining. While Ukrainian leaders are not holding out too much hope that it will get an invitation to join NATO at this summit, NATO’s expansion to Russia’s neighbors is a key component of Moscow’s rationale for the conflict with Ukraine. So how do Russians view NATO? A May 25–31, 2023, joint Chicago Council-Levada Center survey demonstrates that Russians express both fear and defiance in views of NATO and Russia’s ability to counter what the government paints as Western aggression.

Key Findings

Russians seemed to sense more of a long-term than immediate threat from NATO.

- Six in 10 Russians said they have reason to fear Western countries that are part of NATO.

- Nearly half (48%) were concerned that the war in Ukraine could escalate into a Russian confrontation with NATO (48%).

- Seven in 10 said NATO membership for Ukraine would be a threat to Russia (71%), and preventing Ukraine’s NATO membership is seen as a top benefit of the Russian military action in Ukraine.

- At the same time, seven in 10 Russians do not fear an imminent attack from NATO (53% unlikely, 20% absolutely improbable).

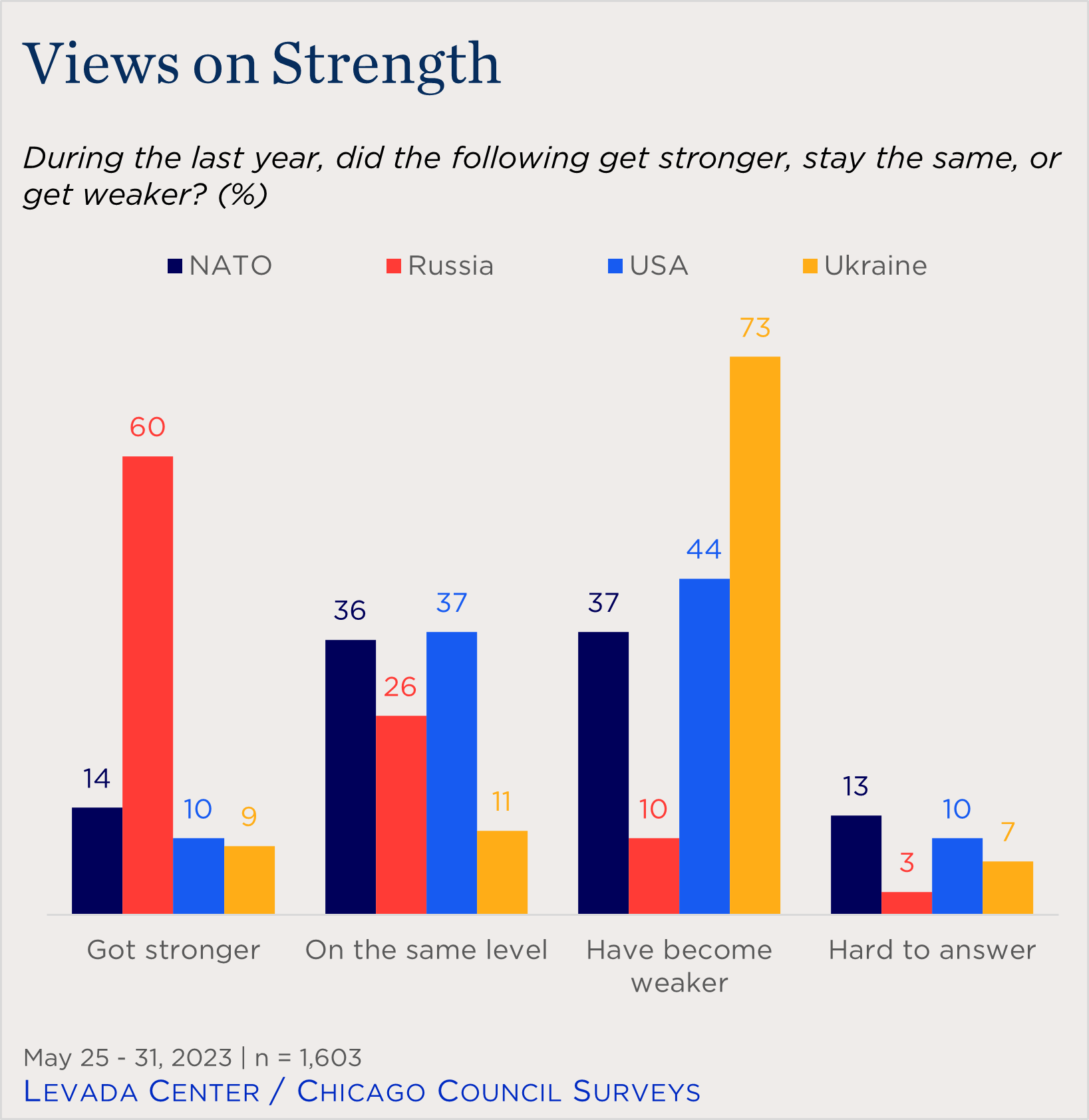

- More Russians said NATO has become weaker (37%) than stronger (14%) over the past year. By contrast, a majority say Russia has become stronger (60%).

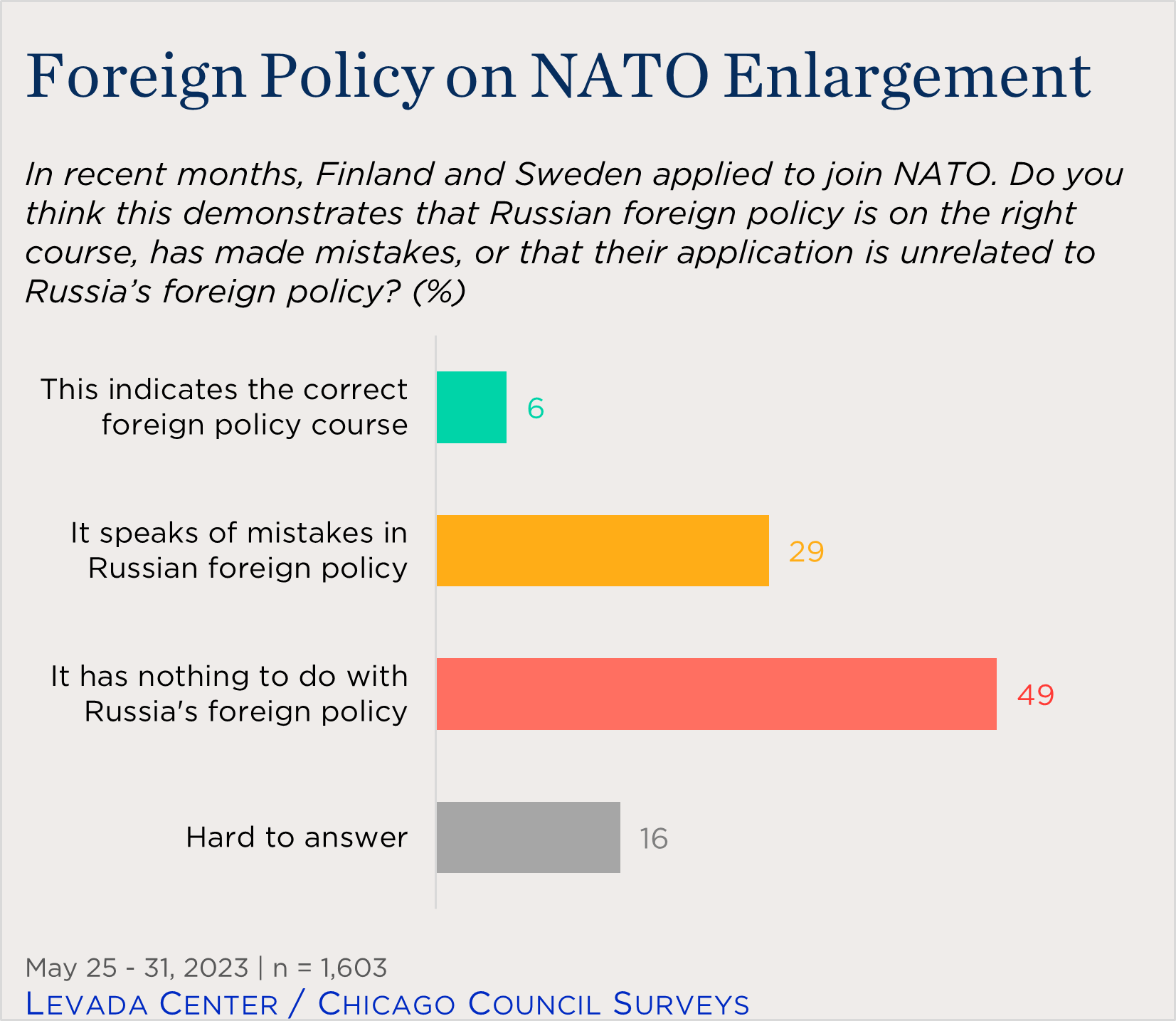

- A plurality of Russians did not believe their country’s actions are responsible for Finland and Sweden’s applications to join NATO (49%).

Russians Considered NATO a Long-Term Threat Justifying the Military Operation in Ukraine

The 2023 NATO summit, held at a venue in Vilnius roughly 20 miles from the Belarussian border, is taking the threat from Russia very seriously, as allies from across NATO have sent troops, air defense, and advanced weaponry to deter an attack while NATO leaders are in town. Meanwhile, Ukraine was making advances in pushing Russia out of Bakhmut in the hours leading up to the high-profile meeting. One former NATO secretary general makes the case for Ukraine joining now; however, routing out Russia is essential for Ukraine’s bid to join the alliance.

Russian President Vladimir Putin has consistently linked this war with NATO expansion. Yet Yevgeny Prigozhin—the head of the Wagner Group who challenged Putin’s government directly by overtaking Russia’s Southern Command at Rostov-on-Don—has criticized the Russian Ministry of Defense (MOD) for “trying to deceive the public and the president and spin the story that there were insane levels of aggression from the Ukrainian side and that they were going to attack us together with the whole NATO bloc.”

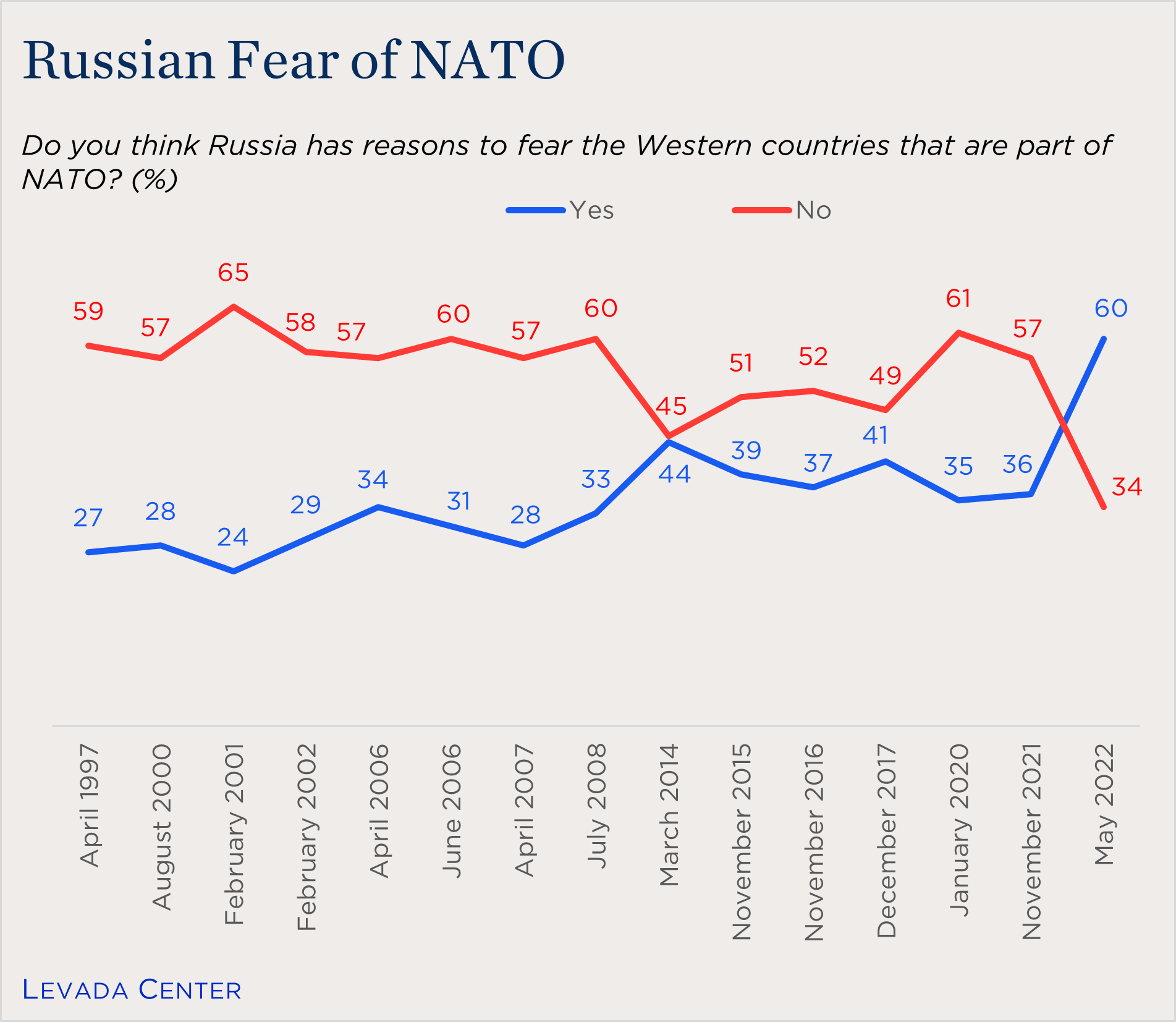

At least at the start of the war in Ukraine, most Russians seemed to accept the official narrative that the United States and NATO countries initiated the escalation in eastern Ukraine (60% in a February 2022 Levada survey). And by May 2022, 60 percent of Russians, up from 36 percent in November 2021, said Russia had reasons to fear “the Western countries that are part of NATO.” In fact, nearly half (48%) said they were somewhat (33%) or very scared (15%) that the situation in Ukraine could escalate into a potential war with NATO.

Potential NATO membership for Ukraine further exacerbates these fears: 71 percent of Russians responded that they would view Ukraine joining NATO as a threat (52% serious threat, 19% some threat). Russians sense a greater threat from Ukraine’s NATO membership than from Finland (34% serious threat, 24% some threat), Georgia (34% serious threat, 23% some threat), or Sweden (30% serious threat, 25% some threat) becoming members of NATO. This discrepancy is likely due to NATO’s Article V, as Ukraine joining NATO with an ongoing war would likely mean other NATO members would intervene.

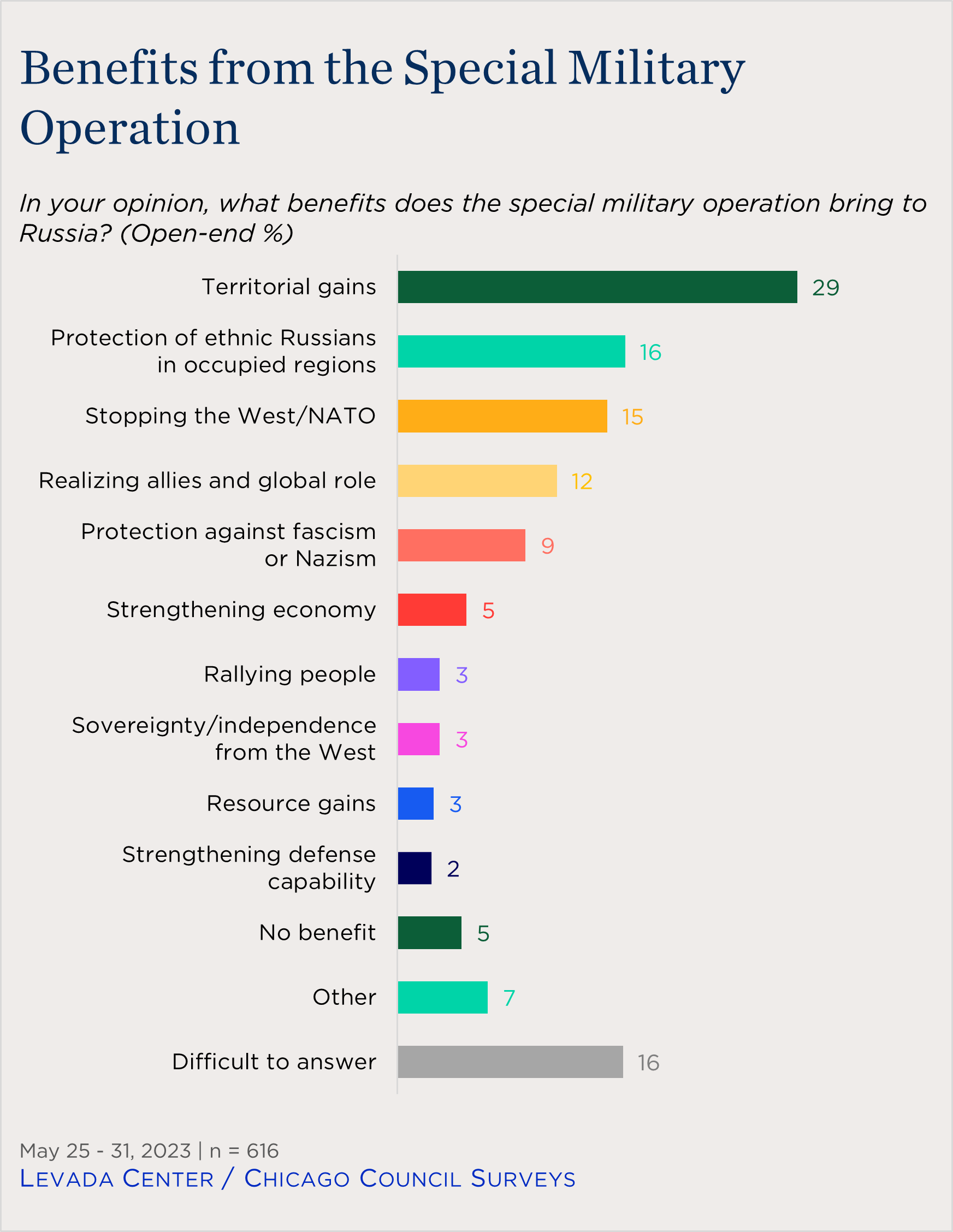

The potential for Ukraine to join NATO could impact how some Russians view the war. This most recent survey, conducted in May 2023, found that Russians were split on whether the military operation brought more harm (41%) or more benefit (38%). A top response to a follow-up question asking those Russians who sense greater benefit what advantages the operation brings was to curtail the threat posed by NATO. The third-most-common response was preventing Ukraine from joining NATO or fighting back against the threat from the West (15% of Russians who view the effort as beneficial). These rate below territorial gains (29%) and protecting ethnic Russians and inhabitants of Luhansk and Donetsk (16%).

Focus groups participants among Moscow residents (conducted in April 2023; one among men, one among women) said a best-case scenario outcome for the war would include a commitment from Ukraine not to join NATO. One man took this further, arguing that the only outcome is “full annexation to Russia, so that there are no incidents in the future, no NATO, because even if the West divides it, and we split it in half, then most likely everything will repeat again. But the worst-case scenario would be that it will come to nuclear strikes because Western Ukraine perhaps will join NATO, and this means nuclear war.” Previous surveys have seen the threat from NATO and the West as the third-most-reported reason for the invasion of Ukraine. Yet, as discussed below, the longer-term threat of NATO expansion appears far more pressing than any potential short-term threats.

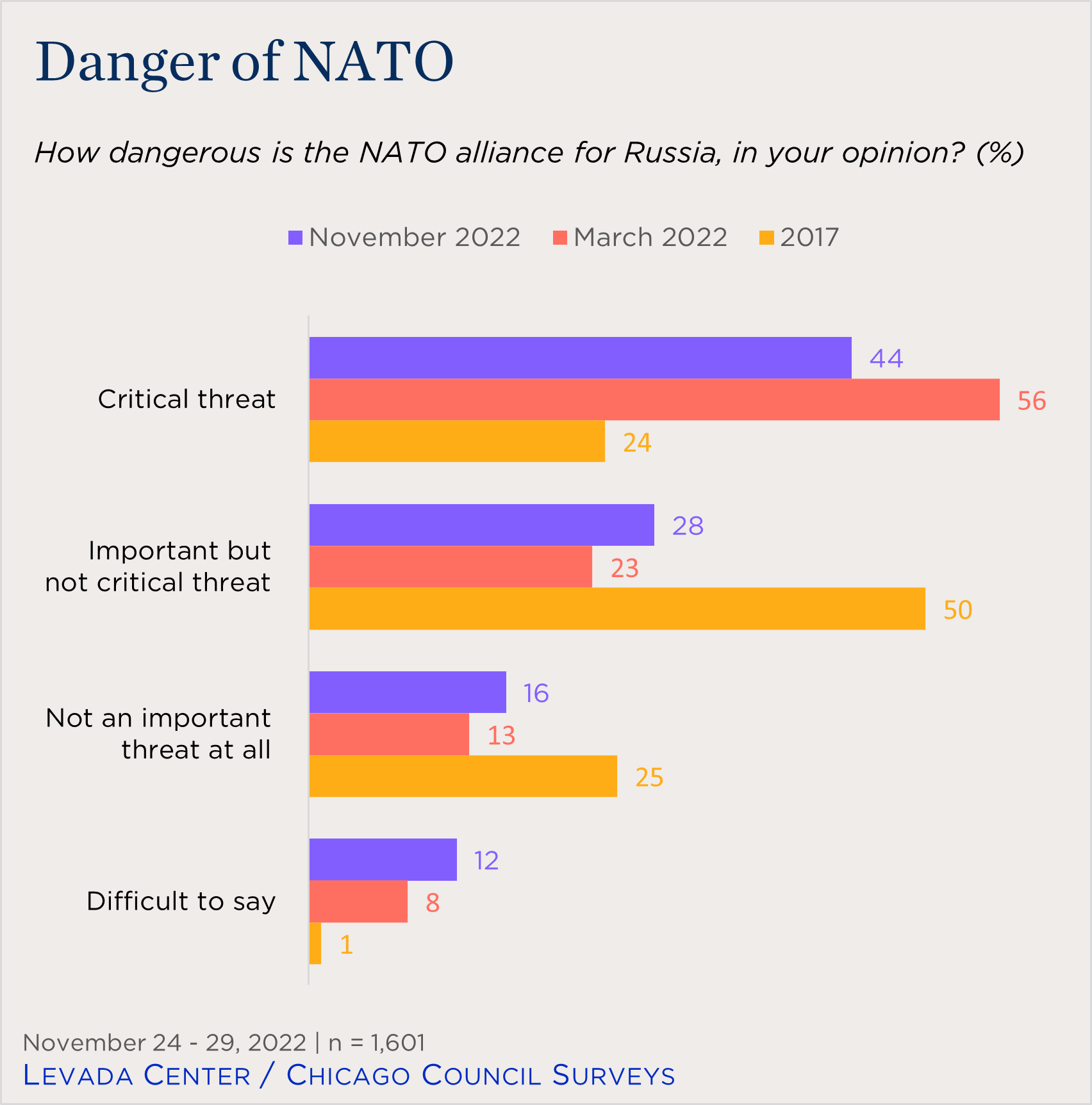

In the Short-Term, NATO Is Considered Less of a Threat

Currently, Russians largely do not fear a NATO attack. When asked how probable a NATO attack is in the coming months, the majority said such a turn of events is “unlikely” (53%) while an additional 20 percent found it absolutely improbable. It is possible that the fact that NATO forces have not entered the war and President Joe Biden’s statements that the United States would not send US troops to Ukraine may have dampened fears about the alliance in Russia, despite all of the military aid NATO countries are sending to Ukraine. In fact, last November, another Chicago Council-Levada Center poll found a 12 point dip in Russians who view NATO as a critical threat to Russian interests (44% in November 2022, down from 56% in March 2022).

Further, roughly one-third of respondents believed NATO is weaker today than it was one year ago, while the same percentage think NATO’s strength is unchanged. Only 14 percent think NATO is stronger. A plurality said the United States is weaker (44%), and a majority said Ukraine is weaker (73%). Some of these responses may reflect defiance as well as some of Russia’s battleground gains in Bakhmut that Wagner forces helped achieve before the start of the Ukrainian counteroffensive. It could also amount to some wishful thinking, given Ukraine’s military strength after a year of combat experience and NATO military aid. Comparatively, the majority of Russians think their country is now stronger (60%).

Focus group discussions touched on both strengths and weaknesses of NATO in the context of the conflict with Ukraine. Most of the men in their focus group seemed to think NATO is weakening. As one male participant posited, “In principle, I can say that NATO remains at the same level, but at the same time, those states that have NATO bases on their territory are weakening due to pressure from the United States. European countries...the economy of European countries, we can say, has already collapsed.” However, a few male participants disagreed, noting that NATO’s budget is “10 times larger than ours” and “they are starting to get stronger, because new countries are joining them.” Female focus group participants were divided on whether the military operation strengthened or weakened NATO. As one woman offered, “Financially they have been weakened after such spending,” prompting another woman to counter, “I think that [NATO is] strengthening, because they have expanded in quantitative terms, they have trained, they have…updated their weapons, so how did they weaken? They're doing great.”

Most Do Not Believe Russia Is Responsible for Finland and Sweden Joining NATO

As some of the quotes above reflect, Russians cannot deny that NATO is enlarging. Finland’s membership is official, and Sweden is on its way. And in a twist from when the subject was last seriously discussed, France’s position—which strongly opposed NATO membership for Ukraine in 2008—has shifted to a position “now closer to that of Poland than Germany” (Poland is advocating for Ukraininan NATO membership while Germany wants to delay it). And yet, in the May survey, almost half of Russians were unwilling to accept this as a byproduct of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine (49%; see figure next page). One male focus group participant offered this view: “To be honest, I don't think Finland and Sweden wanted to join NATO because they are afraid that [Russia] will seize their territories. I think it was done simply because the United States wanted it.” Another man thought the Finns and Swedes might fear a Russian attack, but “the most obvious answer is that they were pressured to join [NATO] by the United States.”

Roughly three in 10 Russians, however, viewed NATO enlargement as a sign of mistakes in Russia’s foreign policy (29%). This view was more common among the Muscovite focus group participants, as one man said, “I think this [war] is a good reason [for Sweden and Finland] to try to join, and…I think they see a threat from Russia, in this regard, that's why they joined NATO.”

Conclusion

Both the general public opinion poll and the Moscow-based focus groups suggest some degree of confusion among Russians around the threat NATO poses and how to leverage any success against the Western bloc. This could be due to several factors. While the Russian media landscape presented NATO as a threat for years and the cause of the conflict, NATO countries have not taken any direct military action against Russia. Second, while there are concerns among Russians about what Ukrainian membership would mean for Russian security, that’s still unlikely to occur while the war is going on. And while NATO is seen as a threat in the longer-term, most Russians feel it is unlikely that the situation with Ukraine will escalate into a conflict between NATO and their own country.

This survey was part of Levada's monthly omnibus survey. The full methodology can be found on the Levada website.

For this particular wave of the Levada Center's monthly omnibus survey, the interviews were conducted between May 25–31, 2023, among a representative sample of all Russian urban and rural residents. The sample comprised 1,603 people 18 or older in 138 municipalities of 56 regions of the Russian Federation (including Crimea). The survey was conducted as a personal interview in respondents’ homes. The answer distribution is presented as percentages of the total number of participants along with data from previous surveys.

The statistical error of these studies for a sample of 1,600 people (with a probability of 0.95) does not exceed:

- 3.4 percent for indicators around 50%

- 2.9 percent for indicators around 25%/75%

- 2.0 percent for indicators around 10%/90%

- 1.5 percent for indicators around 5%/95%

This work is made possible by the generous support of the Carnegie Corporation of New York.

The group discussions were conducted on April 20, 2023, at the Levada-Center’s Studio, among eight men and eight women 20 and older. Participants were selected by professional recruiters in Moscow using the “snowball” method through recruiters’ networks as well as those of previous participants of Levada-Center’s focus groups and were screened by age and gender. Anyone who participated in a focus group less than one year before this study and worked in marketing or political and social sciences was excluded from the selection process. All 16 participants represented average Muscovites with some level of awareness about political news and with a variety of political attitudes.

Related Content

Public Opinion

Public Opinion

While many Russians favor negotiating for peace with Kyiv, they are unwilling to give up any Ukrainian territory seized since 2014. They are, however, more open to a “neutral” status for eastern Ukraine.

Public Opinion

Public Opinion

While a majority continue to express support for the war and more now sense the military operation has been successful, the Russian public is divided on whether it has led to more positive or negative consequences.

Public Opinion

Public Opinion

While more Russians say Moscow should start negotiations than continue fighting, their aim may be to solidify gains rather than making real compromises for peace.

Public Opinion

Public Opinion

But those feeling an economic pinch are more likely to say that Moscow should enter peace negotiations.