Growing Cities, Changing Diets

Water flows between farms and cities and changes form as each person uses and reuses it.

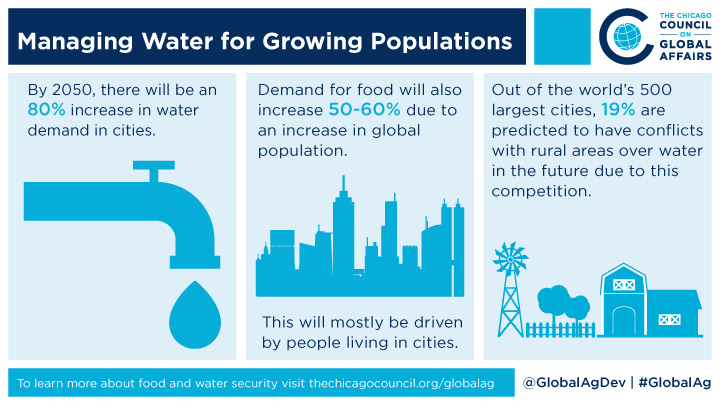

Managing Water for Growing Populations

The thought of running out of water elicited a visceral reaction when Cape Town’s Day Zero approached in 2018. Social media campaigns and platforms sprung up overnight as people grappled with the reality that Cape Town residents would soon be facing. Similar water struggles between cities and the rural communities that surround them are visible around the world, and more are predicted in the future.

Already, a quarter of cities, representing 150 million people, are classified as water stressed. By 2050, 66 percent of the world’s people will live in cities, generating a potential increase in demand for water of 80 percent and significant and likely competition or conflict between cities and rural areas. However, booming population growth will also mean demand for food will also increase by 50 to 60 percent, largely fueled by growing cities and their changing diets. Cities need farmers to produce more food and more diverse foods, but they will also need them to do so with less water so that there is enough go around. A tough but solvable challenge.

A 2018 study published in Nature looked at water demand projections for 485 cities and found that 27 percent of those cities’ water demand would exceed the available surface water by 2050, and 19 percent of cities studied were likely to have conflicts with rural areas due to dependence on the same surface water. The primary solution suggested “Investing in water efficiency opportunities within the agricultural sector,” which uses roughly 70 percent of freshwater globally. In 80 percent of the cities studied, the modeling suggested that improvements in agricultural efficiency could free up the water needed to meet the increased demand of cities.

Choosing who gets the water is not simply about individual water usage. A farmer’s seemingly high water use is an act that transforms water into food. This involves responding to the diet consumers want, which ranges by diet and region of production, but the recommended diet by USDA results in an estimated water footprint of 5631 liters, or 1487 gallons. Since 80 percent of Americans now live in cities, the farmer’s water expenditure very often ends up in the city on the urban dweller’s plate. Although some agricultural products are not food-related, like cotton or flax, they are often used in cities as well.

An important part of sustainable water for all is developing smart water sharing agreements that acknowledge the services that water can provide to specific communities and regions as a whole. However, such arrangements are rarely in place before a dispute and even when they are settled, the best arrangements will be contested when scarcity drives water prices up or restricts usage.

This conflict was seen in Southern California over the past few years between the city of Los Angeles and the well-irrigated surrounding region of the Palo Verde Valley. Their water deal permits the city to pay farmers to allow a percentage of their fields go fallow during times of water scarcity and to share unused irrigation water to service urban water needs. But recently the Los Angeles metropolitan water authority began to acquire farmland in the region directly, allowing them to implement more stringent conservation practices from farmer renters and possibly fallow more land to improve water availability downstream. The Palo Verde Irrigation District filed a lawsuit alleging the city had overstepped the parameters of the agreement by overpaying for the land and becoming a majority landowner in the region to try and assert more control. They also expressed concern that the move could cause long-term economic damage to the rural area. While the suit has since been dropped and negotiations continue outside of the courtroom, this dispute is a good example of how much is at stake for both cities and rural areas and how far each are willing to go to protect its interests.

There should be a longer-term plan that takes a wider view than any one urban-rural water conversation. Given what cities stand to gain from more efficient agricultural practices, they should be strong advocates for agricultural R&D and investing in improved practices to improve water efficiency. Are there good mechanisms, like social impact bonds, that can enable cities to invest in the water efficiency of farmers in their surrounding region long-term? Could arrangements be made to reward farmers for hitting challenging water conservation targets while maintaining their production goals? Are the public and private sector investing enough in safe, innovative technology and infrastructure that helps recycle gray and brown water for use in agriculture?

Ultimately, the choice of who should get 'the water' is a false one. Water flows between farms and cities and changes form as each person uses and reuses it. Both city dwellers and rural residents must think differently about water and the future of the food and water system. We all want similar things for the future: affordable, available food for all, flourishing, profitable farms, and a natural resource base that is sustainably stewarded for future generations. How do we achieve that future? Smart sharing is part of the answer, but we need to do more. Let’s start thinking differently to get there.

"Unchartered Waters" Series

- Farmer-Led Irrigation for Agricultural Intensification

- Achieving Food and Nutrition Security in the Face of Water Scarcity

- Growing Cities, Changing Diets

- The Livestock Ladder’s Water Footprint

- Are the Sustainable Development Goals for Water and Food Working Against One An…

- From Chicago to Uganda, Clean Water is Key to Good Nutrition

- The Gendered Burden of Water