Are the Sustainable Development Goals for Water and Food Working Against One Another?

Food, energy, and water form a nexus in which increased access to one resource puts increased pressures on the others.

Food, Energy, and Water

Can the world be water and food secure at the same time? There are intuitive reasons to think that these goals conflict. A growing and wealthier population puts higher demands on food production and many of the most agriculturally productive areas have become highly water-stressed. While water is a renewable resource, there are constrictions on use; it requires significant amounts of energy to extract it and to turn polluted or salty water into usable freshwater. Meanwhile, while progress has been made, there are still major gaps in basic access to drinking water and water for sanitation and hygiene (WASH) globally. Thus, food, energy, and water seem to form a nexus in which increased access to one resource puts increased pressures on the others.

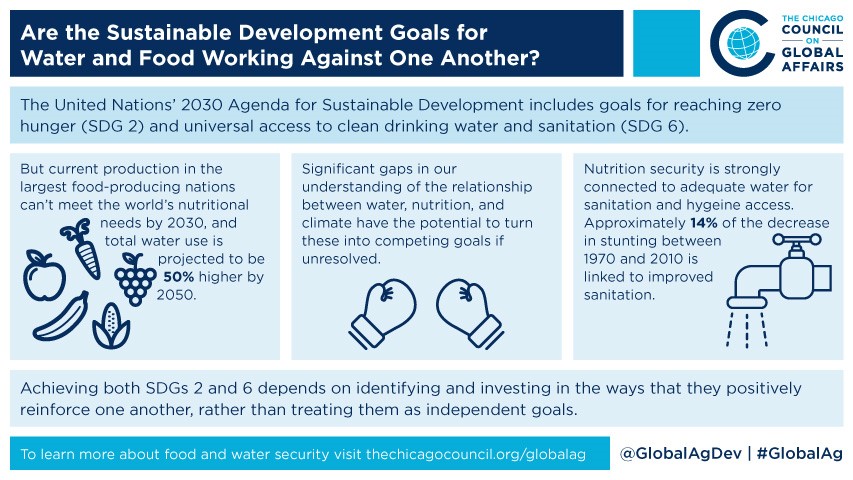

The United Nations’ 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development includes Sustainable Development Goals for reaching “zero hunger” (SDG2) and universal access to clean drinking water and sanitation (SDG 6). To some, these are aspirational goals, but even making substantial progress toward them would be valuable. Yet, there are significant gaps in our understanding of the relationship between water, nutrition, and climate which—if unresolved—have the potential to turn these targets into competing goals.

Avoiding this oppositional stance is important, as both goals are sorely in need of progress. The 2018 SDG report found that global undernourishment and hunger is rising while agricultural aid to developing nations is falling. At current rates of production, the 19 largest food-producing nations will not meet the world’s nutritional needs by 2030, indicating a need for innovation to increase the rate of food production across the globe. At the same time, 844 million people across the globe lack basic access to clean water and 2.3 billion people lack basic sanitation services. Total consumptive water use is projected to be 50 percent higher by 2050 (download report), compared to year 2000 levels.

In the past, innovation has cut off Malthusian catastrophes. The Green Revolution has neatly avoided food insecurity in some places with substantial inputs from chemical fertilizer, new seed technology, and pesticides. While water resources are somewhat more difficult to innovate into existence, the real question is not whether we will totally run out of some critical primary resource like water. Instead, it is whether current methods of production simply shift hazards around between communities or raise the costs of meeting the SDGs so high as to make them effectively out of reach.

Achieving SDGs 2 and 6 together ultimately depends on identifying holistic, cross-sectoral, policies which allow the SDGs to positively reinforce one another, rather than treating them as independent goals. It requires planning for cases in which hard trade-offs will need to be made, while understanding that, even if real, these trade-offs can be temporary. This exposes the areas in which we need to make the greatest leaps in understanding.

Clean Available Water is Essential to Nutrition Security

SDG 2 emphasizes the reduction of hunger, rather than nutrition specifically. These are different—while it is currently possible for the global food system to produce adequate calories to feed the population, getting nutritious food—for example fruits, vegetables, and animal-sourced proteins—to people is more challenging. It’s also much more water-intensive.

Water security efforts related to improving food security are often aimed at increasing the amount of water available for agriculture, or at least reducing the amount of water needed for agriculture. But nutrition security, specifically the ability to improve nutritional uptake of any new production, is strongly connected to adequate WASH access. Contact with contaminated water is a common disease vector—it was responsible for nearly 830,000 deaths from diarrheal disease in 2016 alone. Even if water-borne illness doesn’t kill a person, it can have very negative effects on their life. Approximately 14 percent of the decrease in stunting between 1970 and 2010 is linked to improved sanitation. Being ill reduces the body’s ability to take in nutrition and, if regular enough, can have chronic developmental effects. Women are particularly important targets for these efforts because in many places they are chiefly responsible for water collection and food preparation, and so have the most contact with contaminated water. Meeting the SDG 6 targets for WASH would thus increase the chances of meeting the SDG 2 targets for stunting and for equitable access to nutrition.

Agricultural Water Use is a Gap in the SDGs

SDG 6 is largely silent on sustainable agricultural water use. Meeting the nutrition goals will require significant increases in productivity for smallholder farmers, who make up as much as 80 percent of farms in Sub-Saharan Africa. Weather variability, high seasonality, and low rates of irrigation are a serious obstacle to improving their collective productivity. Expanding irrigation is among the critical strategies for achieving greater food security with variable precipitation. It allows smallholders to farm during the dry season and to produce a wider variety of crops, which improves both food security and income. However, expanding irrigation is also associated with increased water use that can put limited surface and groundwater supplies at risk.

India’s experience with expanded irrigation offers an example. In 1988, India launched the One Million Wells Scheme to improve small-scale agricultural production. While this may have contributed to the nation’s food sufficiency in production, India is still home to one-quarter of the global hungry population. The nation is also facing the worst water crisis in its history, with 70 percent of the water supply contaminated, and groundwater is being depleted at an alarming pace, forming a significant food security risk for the future. Twenty-one of the nation’s major cities are on a course to run critically short of groundwater by 2020.

Making local smallholder farmers more productive and more water-efficient simultaneously is a difficult challenge that requires more focused research. It is possible that more locally-sourced production in less-intensely farmed water-rich places in Sub-Saharan Africa will take some of the pressure off of highly water-stressed places that would otherwise produce crops to export to Africa. Building infrastructure for storage and transport to help smallholders meet local demand might increase water use but relieve water stress in already intensely irrigated places elsewhere.

Filling the Gaps between SDG 2 and 6

There are a number of other important gaps in our understanding of the links between food and nutrition security and water security. Climate change itself contains a number of unknowns—with respect to how weather patterns will affect agricultural productivity and water quality. The further effects of climate on nutrition are even more poorly understood. However, much of the water stress that currently affects agriculture is unrelated to climate change, being caused mainly by pollution and unsustainable patterns of consumption.

In general, sustainable resource development has to be tackled as a component of hunger reduction and agricultural productivity increases. This depends on governments providing stronger legal frameworks and standards to manage the predictable consequences of accelerating growth, as well as intentionally funding sustainable agriculture alongside food security investments.

This is a critical moment for global food security and water security. Even if there are inherent tensions in food and water SDGs—as they are currently written and presuming that patterns of production and consumption remain largely unchanged—they also have important synergies. Failure to investigate these interlinkages and mutually exploit them risks a world which is both hungrier and thirstier.

"Unchartered Waters" Series

- Farmer-Led Irrigation for Agricultural Intensification

- Achieving Food and Nutrition Security in the Face of Water Scarcity

- Growing Cities, Changing Diets

- The Livestock Ladder’s Water Footprint

- Are the Sustainable Development Goals for Water and Food Working Against One An…

- From Chicago to Uganda, Clean Water is Key to Good Nutrition

- The Gendered Burden of Water