Eurasia's Freight Infrastructure vs. Russia's War in Ukraine

Even as the war in Ukraine creates risks, the extensive city-based CEFT network remains resilient from its continued expansion, improved infrastructure, and operational adaptability.

China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) will officially be ten years old in 2023 when President Xi Jinping will lead a national celebration marking his signature foreign policy initiative. A crucial precursor to the BRI, and arguably its most prominent flagship project, the China-Europe Freight Train (CEFT) has already run through its first decade of 2011-21. With 82 routes currently connecting nearly 100 Chinese cities to around 200 cities across 24 European countries and more than a dozen Central, East, and Southeast Asian countries, the CEFT has formed a vast transcontinental freight system spanning both ends of Eurasia. While only 17 freight trains ran from China to Europe in the CEFT’s inaugural year of 2011, 60,000 trains cumulatively will have traversed the Eurasian landmass and its maritime margins by October 16, 2022 when the 20th Congress of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) opens in Beijing.

As the CEFT enters its second decade poised for continued growth, a critical question looms: Is Russia's war against Ukraine disrupting the CEFT, and how? On the one hand, the CEFT has depended heavily on Russia as both the most important terminus and through-corridor accounting for 37 percent of all CEFTs through 2021, leading Germany at 24.3 percent and Poland at 23.4 percent. On the other hand, the CEFT is anchored to a vast network of major and minor cities with grounded flexibility and resilience to weather the Ukraine storm.

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in February 2022 threw a big geopolitical wrench into the CEFT-enabled Eurasian freight network. Complicating this risk is the role of Belarus, Russia’s neighbor and closest geopolitical ally, as the most established through-space for the CEFT to enter the EU via Poland, accounting for 7 percent of all trains through 2021, behind only Germany and Poland. Furthermore, in 2020, a small number of CEFTs began to run from Russia through Kiev and Chop, a Ukrainian city near the borders of Slovakia and Hungary, to enter the EU (see map). This route came to a halt when the war started.

The disruption appears major as the war is the biggest European conflict in eight decades, with severe geopolitical consequences. The disruption is also real, as the war’s risks force logistics companies to raise insurance premiums. Some disruption might arise from an unknown amount of smaller cargo flows between China and Europe, as European companies avoid using the Russian Railway, fearing economic sanctions. Against these perceived or real risks, the CEFT’s extensive geographic coverage, coupled with its diverse routes and linked cities, offer ways and means to bypass or mitigate the war’s risks as the evidence below shows.

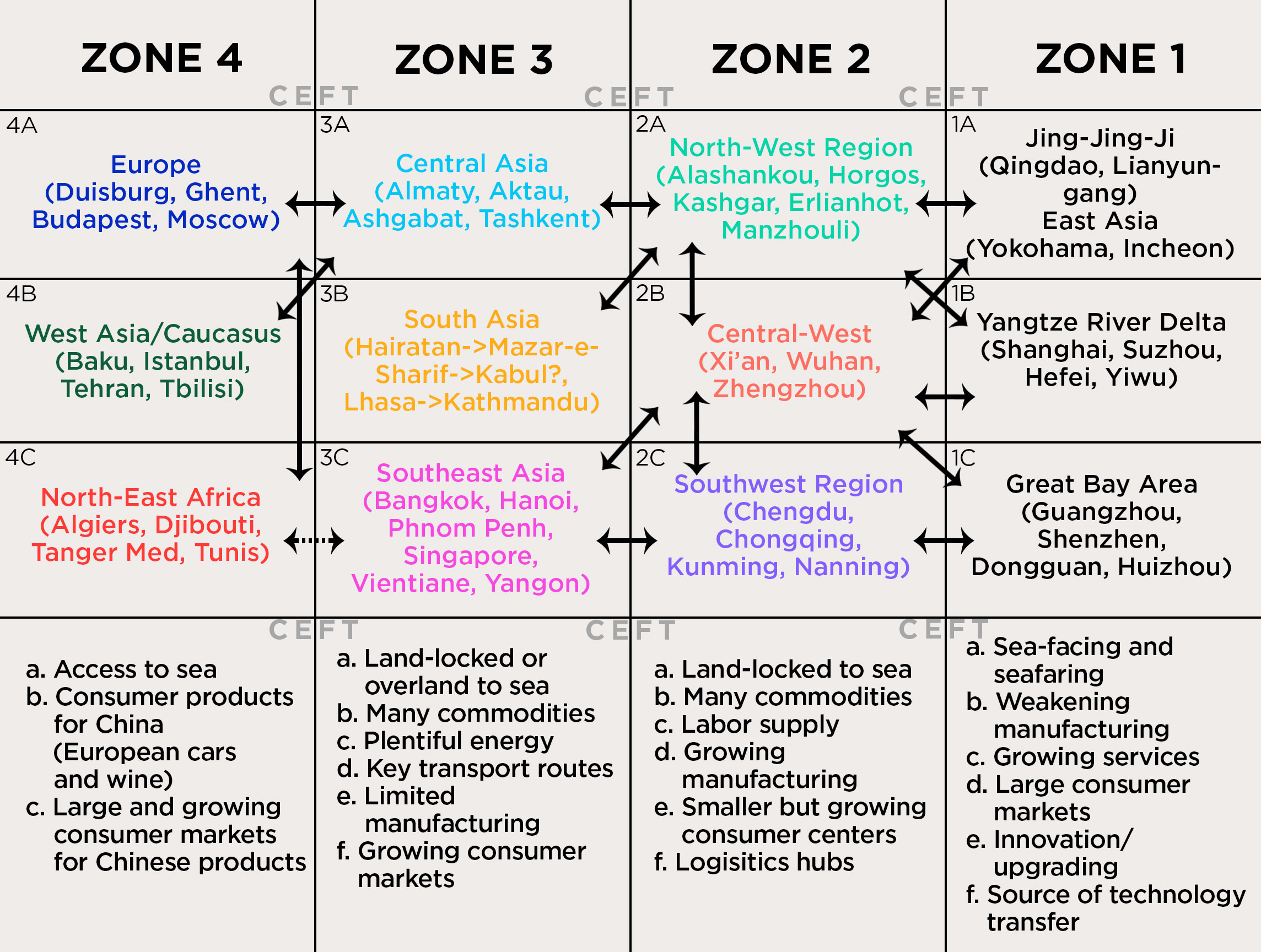

The bedrock of the CEFT is its extensive inter-city shipping links (see figure). Zones 1 to 4 identify four connected regional and 12 subregional zones that contain the departing, in-between, and arriving locations for various CEFT rail and intermodal routes, plus the general geoeconomic conditions facilitating these routes. Zone 1 comprises three subzones of China’s more developed coastal cities, while Zone 2 features three interior and border regions that have become the most active drivers of CEFTs as beneficiaries of China’s “Go West” campaign in 1999 and BRI in 2013.

Zone 3 consists of three regions of Asia that serve as important freight transit hubs and final destinations. Zone 4 covers three regions further west, with continental Europe anchoring the western end of the CEFT network and extended sea shipping links to North-East Africa that reconstitutes traditional Afro-Eurasian trade. The double-headed arrows denote the bidirectional runs east-west across Zones 1-4 and north-south between the A-C subzones.

The China-Europe Freight Train (CEFT)-driven and city-based Eurasian land-sea intermodal freight network spanning four regional zones and 12 subzones

Source: Conceived and updated from author's research and published work.

A common CEFT route would run west from Zone 1 to Zone 4. As an illustration, on August 18, 2020, a freight train carrying electronic products and personal protective equipment (PPE) left the Chinese coastal city of Shenzhen (1C) through 27 Chinese cities including Chengdu (2C), exited at Alashankou (2A), passed through Kazakhstan (3A), and finally arrived in Duisburg (4A). This route reveals the crucial connective role of key CEFT hubs in western China (2B and 2C) in linking China’s powerful coastal manufacturing centers (Zone 1C) to a number of cities in Central Asia and Europe (3A and 4A). To improve supply chains beyond trade, a large Chinese electronics company based in Huizhou (1C) has shipped parts to its factory in the small city of Żyrardów, Poland (located in 4A), faster and more reliably than by sea.

Involving the opposite direction on a broader scale, by August 29, 2022, the International Land-Sea Transport Corridor (ILSTC), anchored to and through Chongqing as its center of operation, channeled over 20,000 freight trains between Europe and Southeast Asia via China and between western China and Southeast Asia terminating at Singapore. Within China, this corridor has incorporated 111 rail hubs associated with 59 cities and 29 sea or land ports across 16 provinces, with extended freight connections to nearly 100 cities in 19 countries between Europe, China, and Southeast Asia. This freight traffic has benefited from the growing overland use of the existing China-Vietnam Railway and the relatively new China-Laos Railway (CLR) to reach Southeast Asian destinations (4A-3A-2A-2B-2C-3C), including sea shipping via the main ports in China’s Guangxi province.

Impact of Russia’s Invasion of Ukraine

Just as the CEFT was stretched further to the eastern edge of Eurasia, the war in Ukraine hit the CEFT on the European end. Many China-based European and US manufacturers and traders suspended orders for shipping on the CEFT while some sought cargo insurance packages that cover war risks. The German automaker Audi, which has extensive supply chains to and in China, stopped using the Trans-Siberian Railway. By early April 2022, the freight volume from China to Europe was down by about 50 percent compared with before the war.

Market demand for freight trains from Shanghai to such key European cities like Hamburg, a sister city of Shanghai, fell by 40 percent in the first month of the war, with the frequency of trains halved. April 2022 also saw Asia-Europe container cargo fall about 56 percent, mostly due to the EU-imposed sanctions on Russia shutting down routes through Kaliningrad via Mamonovo-Braniewo on the Russia-Poland border. All this was not surprising given that 68 percent of the westbound traffic and 82 percent of the eastbound traffic in China-EU overland trade went through Russia in 2021.

Despite all the war-induced disruptions, it did not take long for the CEFT to stabilize its operation and regain momentum. Even in the war’s immediate disruptions during March and April 2022, the number of CEFTs averaged around 1,100, above the mean over the last three years. By May and June 2022, the number of trains rose to over 1,300, comparable to the monthly high in 2021. July and August 2022 saw new historic records of 1,517 and 1,601 trains, respectively, the latter of which was up 21 percent in year-over-year growth. On August 21, 2022, a train left Xi’an and arrived in Hamburg on September 9 through Kazakhstan, Russia, Belarus, and Poland, along the earliest and most established route that appeared very vulnerable to the spillover risk of the war. This train marked the 10,000th CEFT for the year, hitting this round target 10 days ahead of 2021's pace.

How the CEFT Network Adapts

The CEFT’s rebound benefited from key CEFT hubs in China, such as Xi’an, offering war insurance to shippers who were hesitant to run their cargo through Russia in the war’s early days and weeks. As Europe braves for a severe energy shortage this winter due to Russia’s reduced supply of natural gas, it has purchased a lot more energy storage equipment, electric heaters, and electric blankets made in Zhejiang province in eastern China. The number of electric blankets ordered by Europe jumped from 73,000 for February 2022 to 1.3 million for July 2022, led by Germany, the United Kingdom, and the Netherlands. This has helped keep the number of freight trains running steadily from the city of Yiwu to Europe (1B->2A->3A->4A) thus far in 2022.

In another adaptation to the war from the growing number of routes that involve more cities, some rail shipping companies and freight forwarders, primarily those based in China, have turned to an alternative route stretching across Kazakhstan, the Caspian Sea, Azerbaijan, Georgia, and Turkey into Europe, or what is known as the CEFT’s Middle or Southern Corridor. Moving from 3A to 4A via 4B, cargo shipments across Central Asia and West Asia/the Caucasus are expected to reach 3.2 million metric tons in 2022, a sixfold increase over 2021. A small and growing number of CEFTs from established hubs like Chongqing and Xi’an have crossed the Black Sea into Europe via intermodal shipping through the Romanian Port of Constanta into the EU. In April 2022, TopRail, a Romania-based logistics company, dispatched a freight train on a 22-day journey from Suzhou in eastern China to the Georgian port of Poti for crossing the Black Sea into Europe, a record transit time.

Running along these alternative routes, the CEFT has brought more cities like Baku, Tbilisi, Ashgabat, Tehran, and Istanbul into its widening geographic orbit. It also prompts these cities to upgrade their local logistics infrastructure to accommodate more freight rail traffic. As these new CEFT cities allow trains to bypass the risky routes, fully established hubs continue to help the CEFT weather the war’s disruption given their political and administrative autonomy.

While China’s tacit support for Russia since the war broke out, and aggressive stance toward Taiwan, has damaged Beijing's image in Europe, the German city of Duisburg continues to process an average of 50-60 CEFTs a week as Europe’s most important transit hub. Its Office of China Affairs and a commissioner for China affairs at the Mayor's Office coordinate all China-related activities led by the CEFT. This local autonomy insulates Duisburg and other such cities from the geopolitical winds blowing against China-EU relations.

As the war in Ukraine keeps geopolitical tensions high, the extensive city-based CEFT network has acquired sufficient resilience from its continued expansion, improved infrastructure, and operational adaptability. These qualities may ensure the CEFT’s sustainability as an Eurasia-wide freight system.

Learn more about the China-Europe Freight Train and the impact of Russia's invasion of Ukraine on Eurasia's freight infrastructure.

Acknowledgments

This essay was produced as part of the Cities, Infrastructure and Geopolitics Project at the Chicago Council on Global Affairs. It draws partly from presentations and remarks at a series of events and workshops at the University of Oslo (UiO), the Center for Development and the Environment (UiO), the Norwegian Institute of International Affairs, and the ASIANET 2022 conference in Oslo and Trondheim, Norway, the Belt and Road Institute in Stockholm, Sweden, and the University of Bonn, Germany, during June 2022. The research undergirding this writing is supported by the Paul E. Raether Distinguished Professorship Fund at Trinity College, Connecticut. He can be reached at xiangming.chen@trincoll.edu.