The Council's polling experts examine how American foreign policy experts think of the term "allies," and whether variations in thinking matter for US foreign policy decisions.

“America is back,” President Joseph Biden pronounced at the State Department in February 2021. His comment ostensibly meant the United States was returning to the international fold after leaving a global leadership void during the Trump years. The previous administration had downplayed—even discounted—American alliances as key US foreign policy tools. “We will repair our alliances and engage with the world once again, not to meet yesterday’s challenges, but today’s and tomorrow’s,” Biden stated. At the NATO summit four months later, Biden reiterated his administration’s key message and commitment to the alliance. Emblematic of this commitment, he and British Prime Minister Boris Johnson also signed a “New Atlantic Charter” recommitting both nations to their “alliances and partners.”

The United States is unique in the world in terms of security alliances. The country enjoys “the largest and most enduring military footprint” in recent history. From military bases to providing training and material assistance, this footprint is largely enabled through allies. Hence, it is perhaps unsurprising that recent surveys show a perception among Americans that alliances largely benefit the United States.

But what is meant by the term “allies”? Given the variety of military partnerships and relationships maintained by the United States, it shouldn’t come as a surprise that the term “ally” is used to describe countries across this range of relationships. Some countries have a formal defensive treaty with the United States, while others are merely recipients of US military financial aid. How do American foreign policy experts think of the term “allies,” and does variation in such thinking matter?

Do Treaty Allies Matter?

The definition of an ally seems to resonate differently for US foreign policy experts depending on the particular circumstance. International relations researchers often think of allies as “treaty allies.” These allies are conceived as a result of “written agreements, signed by official representatives of at least two independent states that include promises to aid a partner in the event of military conflict, to remain neutral in the event of conflict, to refrain from military conflict with one another, or to consult/cooperate in the event of international crises that create a potential for military conflict.” The North Atlantic Treaty, which undergirds the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO), is of course a prime example.

But according to many US policymakers, Israel too is an American ally. Israel and the United States do not share a written security and defense agreement a la NATO. Rather, the two countries share deep historical, ideational, strategic, and economic ties. Even though they do not have an official defense pact, former US Ambassador to Israel Michael Oren described Israel as “the ultimate ally’ of the United States.

In recent years, US officials began calling an even wider variety of actors allies. These days, some would describe the relationship with Ukraine as an alliance. The United States even dubbed the Kurdish groups fighting against the Islamic State or ISIS in Syria its allies. When former President Donald Trump decided to withdraw US troops from Syria, many in Washington decried the decision, arguing that it would hang America’s Kurdish allies out to dry. From Republican Senator Lindsey Graham to the 2016 Democratic presidential nominee Hilary Clinton, leaders from both sides of the aisle invoked the term to summarize Washington’s relationship with the Syrian Kurds. Meanwhile, Turkey, an actual treaty ally of the United States through NATO, condemned this language. That country has been fighting a war with Kurdish militant groups in the region for more than three decades. How could Turkey’s NATO ally consider Syrian Kurds—a stateless group with clear ties to regional terrorist organizations such as the PKK (Kurdistan Workers’ Party)—an ally?

These recent episodes suggest that treaty alliances are perhaps not as significant for some US foreign policy elites as we expect them to be. On the one hand, Biden’s first foreign visit to Europe to attend the NATO summit suggests that Washington values this alliance. This is following the visit to South Korea and Japan in March by Secretary of Defense Lloyd Austin and Secretary of State Anthony Blinken. On the other hand, not all treaty allies appear indispensable to the United States. The fallout with Turkey, over Washington’s support for the Kurds and Ankara’s purchase of missile systems from Russia, is indicative of this point.

America’s recent behavior signals that an “ally” is in the eye of the beholder—and sometimes, even at the expense of treaty allies. Although international relations scholars consider interstate defense treaties the cornerstone of alliances, it is clear that neither the leaders in the United States nor the public in Israel, Ukraine, or northern Syria would reject the term to describe their relationship with each other. So, how critical is an alliance treaty for shaping US foreign policy?

A Survey Experiment among US Foreign Policy Leaders

To find out whether experts place greater importance on particular types of allies over others, researchers from the University of Illinois at Springfield, the University of Chicago, and the Chicago Council on Global Affairs fielded an experiment among US foreign policy experts/opinion leaders. Between October 2020 and January 2021, nearly 700 respondents who work in Congress, various federal agencies that engage in international affairs, foreign policy think tanks, and US-based universities as international relations scholars were surveyed. The goal was to understand whether the respondents would alter their policy preferences depending on how we described the various types of groups that could be characterized as an ally.

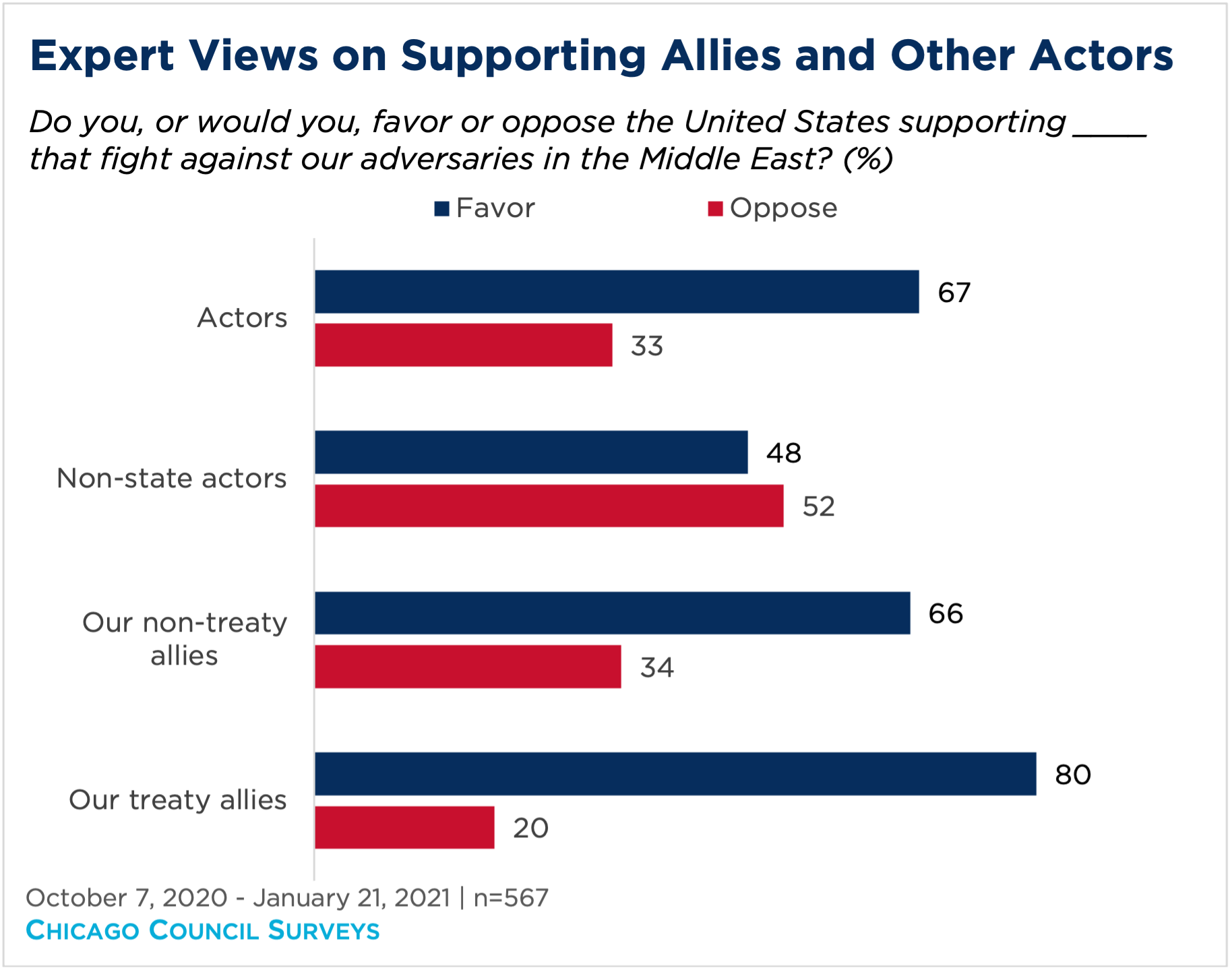

To do so, respondents were asked whether they would favor or oppose international groups that fight against US adversaries in the Middle East. Respondents received one of four scenarios with varying wording to capture the type of ally: treaty ally, nontreaty ally, nonstate actor, or, simply, actor.

US Foreign Policy Elites Favor Treaty Allies over Other Types of Actors

The results show that foreign policy experts in the United States consider treaty alliances to be the most important type of relationship. Of the respondents who received the question with the wording “treaty ally,” 80 percent said they would favor the United States supporting these types of groups that fight against US adversaries in the Middle East. When asked about a “nontreaty ally,” support dropped to 66 percent. Most dramatically, a majority of respondents who received the “nonstate actor” scenario said they would oppose the United States supporting these actors, even if they fight against US adversaries in the region. Though our wording of the question was exactly the same otherwise, how the specific group was defined generated different degrees of support from the respondents (further analysis shows that these differences are statistically significant as well).

But This Support Is Not Unconditional

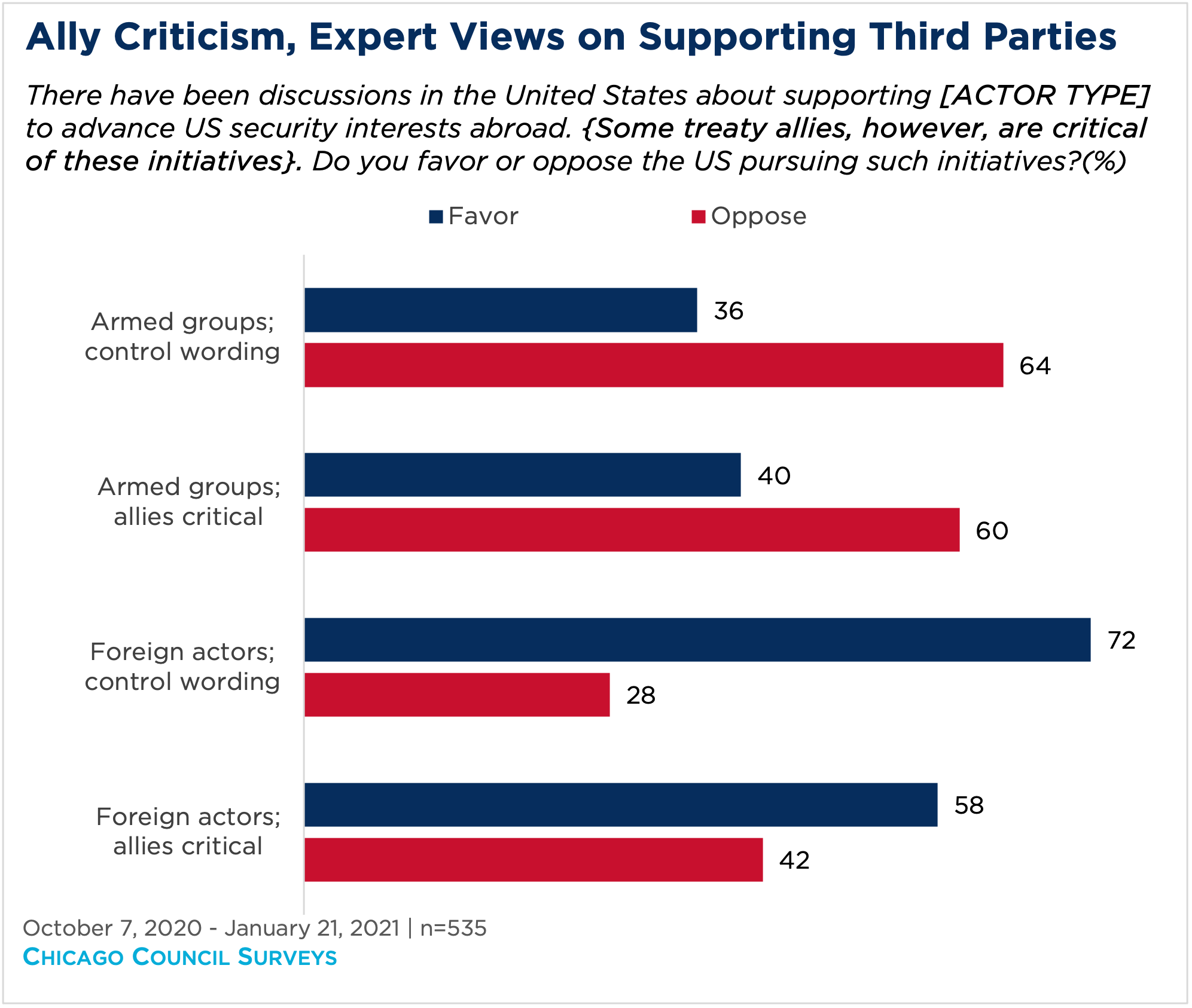

A second experiment examined whether foreign policy experts would prioritize America’s relationships with its treaty allies over other types of allies. To do so, respondents were first randomly presented with one of four scenarios. The control group received the following question: “There have been discussions in the United States about supporting foreign actors to advance US security interests abroad. Do you favor or oppose the US pursuing such initiatives?”

In a second scenario, the following note was added to the question: “Some treaty allies, however, are critical of these initiatives.” A third scenario presented respondents with wording that used “foreign armed groups” instead of “foreign actors” to further specify the nature of the actor that the United States was cooperating with.

The results were intriguing. The respondents were significantly less likely to support a foreign armed group than a foreign actor more broadly. However, there were no statistical differences in each of the cases that included the wording about treaty allies being critical of the initiatives. In other words, the position of the treaty allies themselves did not matter for our respondents.

Both Good and Bad News for Treaty Allies

This is mixed news for treaty allies. The data show that US foreign policy experts place a significantly higher value on America’s treaty allies than other types of international actors. That’s good news for the allies indeed. However, this is not an unconditional relationship. The data seem to say that national security interests are still the top priority for these elites, and they think treaty allies can be pushed aside to realize them. The Biden administration’s Afghanistan withdrawal is one example, which some commentators, like the New York Times’ David Brooks, view as a betrayal of US allies and values, but which Biden himself has strenuously defended as in the US interest.

These findings are of particular importance for Turkey’s relationship with the United States, which has been rocky for some time now. Our study suggests that the frictions between Ankara and Washington could prompt US policymakers to put relations with Turkey on the backburner in the interests of US national security moving forward. Turkey’s potential future efforts to mend its relationship with the United States were signaled at the bilateral meeting between Biden and Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan during this summer’s NATO summit. Our findings indicate that this would be a smart foreign policy direction for Turkey if it wants the United States to take this alliance more seriously.

Methodology

This report is based on data from a survey conducted between October 7, 2020, and January 21, 2021, among staff at various federal agencies that engage in international affairs and in Congress (n=203), fellows and other experts at foreign policy think tanks (n=208), and international relations scholars at US-based universities (n=240). The authors acknowledge financial support from the University of Illinois-Springfield through a Competitive Scholarly Research Grant 20-09 and outstanding research assistance from Gianna Messina.

Related Content

Defense and Security

Defense and Security

Mira Rapp-Hooper joins Ivo Daalder on Deep Dish for a discussion about the state of US alliances at a moment when new concerns are flaring up.

US Foreign Policy

US Foreign Policy

While Americans of all political stripes remain committed to allies and alliances, the public is divided along partisan lines on the value of international organizations.