From Simple to Great, from Past to Future

Lima 2035 shares their ambitious plan to change urban food systems to transform the world’s driest megacity.

The first successful moonshot in 1969 gripped the global imagination. Media around the world struggled to find the words to express their awe and understanding of this incredible feat.

While the world marveled at this once-unimaginable expression of Science, the researchers and engineers behind the scenes knew it all had started with the basics: the principles of mathematics engaged with the laws of physics to help three astronauts “slip the surly bonds of Earth” and land safely on the Moon.

Problem solving has always been a quest to simplify and build. The Noble Prize-winning scientist, Richard Feynman, dedicated much of his career to developing techniques for reducing earthly riddles from a complex whole to an essential puzzle that could be addressed using available tools wedded to emerging technologies.

In this way, Lima 2035—a diverse group of scientists, innovators and food system experts led by the International Potato Center (CIP) and Grupo Alimenta in Peru—has committed to a moonshot of its own using simple innovations to leverage Lima’s urban food system to transform the world’s driest megacity into a lush, regenerative oasis of agro-biodiversity. Through a novel combination of traditional and forward-looking technologies that involve fog harvesting, urban farming, and community food hubs, their vision could herald transformative possibilities for urban areas everywhere.

Growing Food in Impossible Places

"When I arrived in Lima, I was expecting to find luscious green fields. To my surprise, all I saw was a sea of sand. No running water. Nothing green here. An impossible place…"

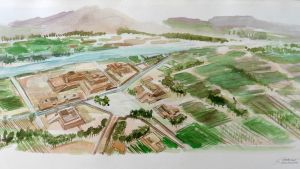

Set in the northernmost tip of the Atacama Desert, Lima is the driest megacity on Earth – a photo-negative image of the New World Eden that thrived here 500 years ago. Upon Pizarro’s arrival in 1535, the Incas had created a lush valley of vegetation, a natural oasis of sustainable agriculture and biodiversity supported by an ingenious irrigation system the likes of which the world had never seen.

Today, standing on the Pacific ocean coast looking east, the challenges before Lima are stark: concrete buildings and high-rises cover 90 percent of the valley and fewer than six miles inland parched brown hills rise precipitously, completely vacant of green space: a South American Dust Bowl that receives less than one inch of rain per year.

Play Video

Play Video

Drone footage captured here illustrates the stark reality of Lima, a city of 11 million people where two million lack access to water, creating a host of health and nutrition-related complications.

In these conditions, restoring Lima’s verdant past seems unthinkable, but – according to CIP’s lead innovation scientist, Soroush Parsa – it is possible. “The challenges are formidable. Here in Lima, we have 11 million people. Four million people live the pueblos jóvenes (slums) around the city and two million of those people lack access to running water. You can imagine the health complications associated with that kind of statistic,” says Parsa. “Family life is a daily struggle to pay bills and provide nourishing food.”

Lima’s slums were established after mass migration from the Andes region to Lima began in the 1940s. Life in these areas is characterized by a prevalence of disease and malnourishment well above national averages: 35 percent of children are anemic and 66 percent of adults are overweight or obese.

Without access to clean water for drinking, preparing food, or for personal hygiene, no food system can be healthy. People in Lima are in desperate need of climate-resilient solutions to support water access and healthy diets. But status quo development and a government with few resources has thwarted previous attempts to improve these conditions.

A Bridge to the Past: "Life here was not always so bleak…"

"Pre-colonial Lima was a verdant landscape of farmland, fruit orchards and lush hills with abundant flora and fauna."

Lima 2035 was the brainchild of a group of Peruvian professionals seeking to pro-actively address challenges facing this city, which is home to the oldest university in western hemisphere (The University of San Marcos). Over the course of many discussions, they recognized that an innovation approach to food systems could be used to help the Lima solve its many challenges related to water and nutrition.

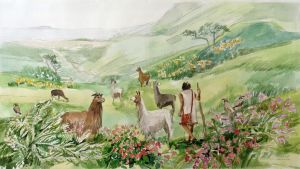

They realized that the greatest strength for Lima 2035 is the country’s unparalleled 5,000-year agri-cultural legacy. New Limenós are the children of two of the world’s original homelands of food production, the Andes and the Amazon. The group understood that Peruvian knowledge of the land and its rich, diverse culinary traditions still formed a strong undercurrent in the city but that knowledge needed an outlet, a revitalization. Their question became: How to revive this ancient knowledge to inspire a food system transformation?

As a first step, they decided to submit a proposal to the Rockefeller Foundation’s Food System Vision Prize competition, a call for ambitious ideas to confront global food challenges over next half-century. Collecting input from a wide range of urban planners, designers, architects, historians, farmers and food system experts, the Lima 2035 proposal was selected as one of 10 “Top Visions” from more than 1,300 applications.

The Lima 2035 project was named a “Top Visionary” by the Rockefeller Foundation in its Food System Vision Prize competition, one of 10 chosen from 1,300 applicants.

The vision builds upon three simple innovations – fog harvesting, urban rooftop farming, and community food hubs – that will produce cascading effects for improved nutrition and inclusive economic growth in Lima. From these ideas, human needs for food and a dignified livelihood can be jointly addressed from the comfort of home, building blocks for a quantum leap forward to a regenerative and nourishing future.

Parsa calls the vision “radically-inclusive,” a blueprint to create a “paradise renewed through collaborative problem-solving by using resources wisely and creating novel connections and broad-based consensus among farmers, citizens, government, NGOs, and private sector actors.” The results will help bridge inequality gaps in food and water access, which will be essential for advancing the country to achieve the 2030 Sustainable Development Goals.

Pre-colonial Lima featured a biodiverse agriculture supported by a complex irrigation system.

Hinging the vision on ideas of food citizenship was a natural connection, according to Vasco Masias, the president of Grupo Alimenta. “Food is to Peruvians what soccer is to Brazilians. We are living in the site of an indigenous civilization who had transformed the desert through irrigation. Lima is poised to rise again to the glory of its pre-Hispanic past by providing everyone access to clean running water and sufficient, healthy food.”

Crawl, walk, run, fly… moonshot!

"A green Lima… with urban farming and small livestock. It takes me back to my roots, to living life as our elders taught us from childhood. A perfect fit, like a ring to a finger."

Though Lima sits in the desert, its inhabitants live beneath a dense airborne aquifer. Every day, evaporated water from the Pacific Ocean flows inland until it reaches the Andean foothills where it gives life to an ecosystem known as lomas or “fog oases,” greening an area 40 times larger than Central Park in New York City. In these lomas, Peruvians have been harvesting water using crude plastic nets stretched over wooden poles.

With some modern upgrading of materials and a design inspired by Chilean architect, Alberto Fernandez, the first innovation of Lima 2035 will be small farms of water harvesting towers that can re-claim up to 10,000 liters of clean freshwater per day from thin air. Just establishing a few farms could result in up to 20 million liters of additional water for the city annually.

Fog harvesting towers placed in lomas can harvest up to 10,000 liters per day, bringing water to the more than 2 million Limenós who lack regular water access.

Greater availability of water will be fundamental to Lima 2035’s second innovation: compact and efficient roof-top farming units that unify the cultivation of plants, animals, and living soil in a circular, regenerative nutrient loop. This low-input, high-output system, will transform homes into farms. And families can benefit from added vegetables in their diets and sell the surplus.

Urban rooftop farms provide an easy and low-cost way for families to grow healthy food and raise incomes.

But where to sell the additional produce?

Lost in time and scattered across the dense urban fabric of Lima are physical traces of ancient past. The Inca called them “Huacas,” or sacred places. Seen from above today, these abandoned archeological sites appear as black holes encircled by encroaching urbanization.

The third innovation of the Lima 2035’s vision will re-cast these Huacas as food hubs, community spaces where food education and culture meet in a productive dialogue to reinvigorate Peru’s ancient culinary traditions. Inspired by urban designer, Jean Pierre Crousse (a Lima 2035 member), these food hubs will function as a 21st century commons, offering an open and inclusive space for the exchange of ideas about food, nutrition, and urban farming.

Ancient huacas in Lima are mostly deserted and un-used. Lima 2035 plans to convert these valuable spaces into community food hubs where people can sell surplus produce and learn more about urban farming, healthy diets and cooking.

Taken together, these three simple innovations unlock the potential to empower the “farmers within” all Peruvians and to re-establishing important connections between urban life and sustainable living.

Preparing the Launch Pad

Beyond the benefits for 11 million people in central Peru, Lima 2035 member Gonzalo Villarán hopes the project will provide a template for replication as the vision ultimately reveals the power of bringing together innovation and tradition by looking into the environmental past to solve environmental challenges of the future. “We believe these ideas can be adapted to locations around the world where people have become disconnected from their food systems and where current food production is unsustainable and unhealthy.”

Masias agrees. “The real value of a vision like Lima 2035 is to promote the power of “public-private-people partnerships” to reverse trends of extraction toward climate-resilience, agrobiodiversity and equitable access to resources – three building blocks of a sustainable future in any location.

Lima 2035’s cultivation at CIP was, according to Director General, Barbara Wells, a natural fit. “As a CGIAR research center, the vision represents the very best of what we do for food, land and water systems transformation. Working with partners, we embrace holistic thinking and grand visions and ground those aspirations in science-based evidence and research to create a viable plan and path for change.”

The work of the Lima 2035 team has begun in earnest as they search for support while moving forward on the initial innovation to build fog harvesting towers in the foothills east of the city.

“Visions like Lima 2035 are a great example of the importance of—and opportunity for—innovation during a crisis. This is even more urgent given the severe stresses placed on food systems as a result of the Covid-19 pandemic,” says Roy Steiner, Senior Vice President of the Food Initiative at The Rockefeller Foundation. “We look forward to seeing how they move their ideas from vision to action.”

For Lima 2035, that vision to action will start with simple steps, unleashing potentials that will give flight to a new Lima, a “moonshot” of sorts transforming a food system to create a re-generative future with access for all.

"Harvesting Tomorrow" Series

- How One Plant Breeder Innovates to Tackle Potato’s Biggest Challenge

- Could a Data Sharing Protocol be Agriculture's Missing Link?

- When Intermediary Links in the Supply Chain are Weakened, the Whole Food System…

- We Can't Shoot for the Moon without Space Technology

- Good Nutrition Today is Key to Harvesting a Better Tomorrow

- Bridging Gaps to Achieve Good Food for All

- From Simple to Great, from Past to Future

- Global Food Security Symposium Highlights Innovation

- Food Security Recovery is More Affordable than You Think

- From Molecule to Market: Using Innovative Plant Breeding to Build Global Food S…

- Closing Investment Gaps in African Aquatic Foods

- Reenvisioning a Fractured Global Food System

- Dietary Diversity for Women Improves Nutrition Security for All

- A Gender-Responsive Approach to Natural Resources