Chicago transit confronts a fiscal cliff, but it isn't Caracas

Chicago's transit system may need to make cuts and raise fares after COVID relief funds phase out, but riders won't likely see a systemic collapse like Venezuelan commuters experienced in the 2010s.

Chicago’s transit system is running out of road. During the pandemic, the Chicago Transit Authority received over $900 million in COVID relief funds from the American Rescue Plan, but that funding is set to run out in 2025. Now, elected officials warn the CTA is fast approaching a fiscal cliff.

If CTA goes over that cliff, could the system collapse? What does a transit breakdown look like?

A transit apocalypse is unlikely, associate professor Kate Lowe told ChicagoGlobal, but a budget crisis could force fare increases and service cuts.

Lowe, who studies transportation and equity at the University of Illinois, Chicago, worries that cuts could exacerbate CTA’s fiscal crisis and set off a vicious downward spiral. Still, while the CTA is in a difficult position, the transit system has inherent strengths that make it resilient to the kind of rare systemic collapses seen in metros like Caracas — the largest city in Venezuela — where twin economic and political crises have eroded the foundation of the transit system.

CTA's funding crisis: Transit's negative feedback loop

While no one knows for sure what lies beyond 2025’s fiscal cliff, it’s likely to be a bumpy ride.

“It’s not just one drop,” Lowe said. “After those relief dollars dry up, we’ll have an ongoing crisis.”

This is, in part, because both CTA and Metra ridership steeply declined during the pandemic. Though CTA reported a post-pandemic ridership record in 2023, ridership is at 60% of pre-pandemic levels. And there’s a big hole in the regional transit budgets, which relied on fare revenue and other system-generated income for about 39% of operating expenses in 2019.

“The concerns over a possible fiscal cliff are real,” CTA’s spokesperson told ChicagoGlobal.

The spokesperson also said that the CTA has “been a good steward of the COVID relief funding.” However, with lower ridership the region’s transit agencies — CTA, Metra, and Pace — anticipate a cumulative $730 million budget shortfall by 2026.

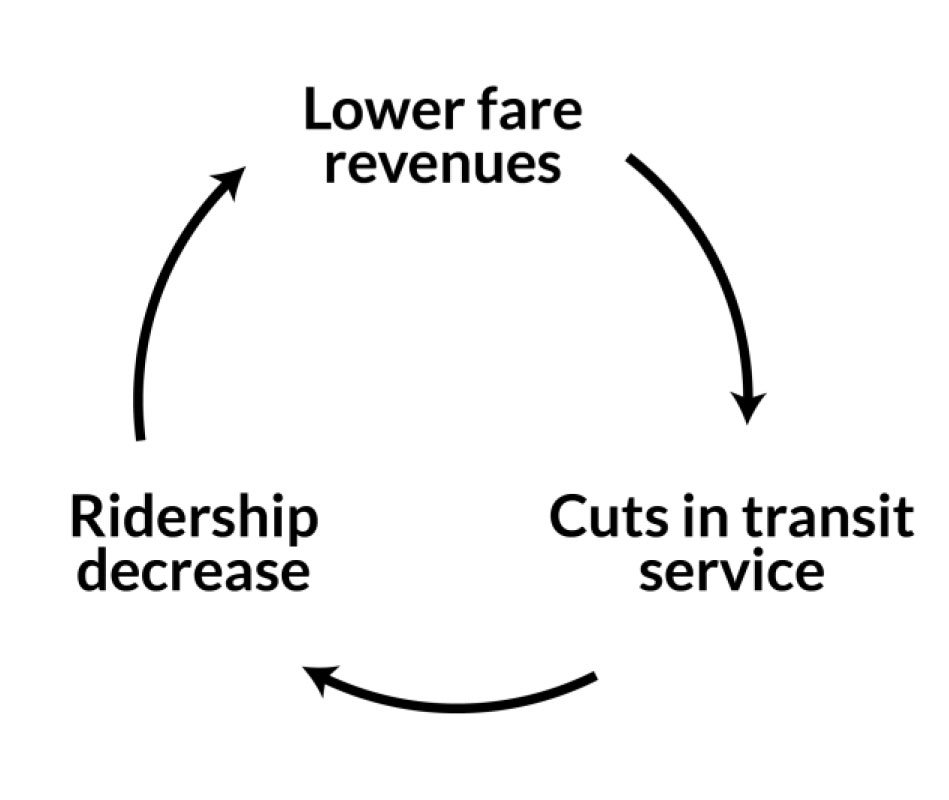

When transit systems like Chicago’s depend on fares, drops in revenue put pressure on transit operators to cut services. This, in turn, can lead to a decrease in ridership, which then spurs even lower revenue and prompts more cuts, according to a 2023 report from the Urban Institute.

“CTA recognizes that without additional revenue streams, it may be faced with drastic service cuts, employee layoffs, or other unwanted cost-saving measures,” the agency told ChicagoGlobal. “It is too soon to know what, if any, steps CTA will need to take to avoid these draconian measures.”

During past budget crises, like in 1992, the CTA reduced hours or closed L stations. Some of them never reopened, including the Wentworth and Harvard stations in the majority-Black neighborhood Englewood, as well as the Laramie station in Cicero. That’s how transit systems’ fiscal distress spreads to households: When trains and buses run less frequently — or not at all — trips to and from work become longer and more expensive, or in the worst case, unviable, Lowe said.

Workers have to find new jobs. Trips to see family can take twice as long. Would-be riders might feel forced to take a $50 Uber ride for a can’t-miss doctor’s appointment, instead of taking a chance on unreliable transit. That eats into grocery budgets or electric bills.

Cuts also can make riders feel less safe. The Chicago Metropolitan Agency for Planning found that, after the pandemic, safety and security “emerged as primary areas of rider concern” and that “decreased service reliability and frequency [were] leading riders to feel less safe.” Anxiety over safety, Lowe said, was also compelling CTA drivers and operators to leave their jobs, fueling a staffing shortage.

Violent crime on CTA trains rose from 2020 to 2022, though system-wide crime is still below its peak in the last 20 years, in 2011. Lowe has also found that riders’ concerns about safety don’t always align with their risk. Fears about crime can be racialized or driven by the stigmas attached to certain neighborhoods.

“The people that are afraid are not always the people that are most at risk,” Lowe said.

All these challenges might sound insurmountable, but Lowe is optimistic.

“We’re not so far into a system degrading that we can’t make transformative change,” she said.

CTA signage at the Granville station in Edgewater, just south of Loyola University.

A CTA bus waits outside the Thorndale station on the Redline.

Caracas' crisis

Though Chicago faces severe challenges, it’s less stressed than Caracas’ foundering transit system, which is under dire strain.

“There is an economic crisis that is compounded by a political crisis,” professor Donald Kingsbury, a Latin America expert at the University of Toronto, told ChicagoGlobal. “And they’ve become self-reinforcing.”

Kingsbury explained that Venezuela’s economy depends on oil revenues, but prices and production collapsed in the mid 2010s, and the state oil company was mismanaged. Western sanctions cut off Venezuela’s access to its foreign reserves and made it more difficult to import goods. Droughts sapped electric plants that depended on hydropower. The state couldn’t keep the lights on, let alone run trains.

The transit system felt it all. For five months in 2018, two million people rode the Caracas metro for free every day because the state company in charge of the transit system ran out of paper to print tickets. A local nonprofit reported in 2019 that 85% of escalators were broken In one Venezuelan city, up to 90% of public bus lines have stopped operating because replacement parts for broken buses aren’t available or are too expensive, according to Caracas-based media outlet Efecto Cocuyo. The public transit system has been attacked by opposition protests as a symbol of the government.

Before living in exile in Spain, Hugo Pérez Hernáiz taught at a university in the center of Caracas. He told ChicagoGlobal that although he didn’t have to travel far to get to work, his bus and metro commute took hours. And that was before Venezuela’s transit system started to crumble.

Then, in 2017 and 2018, he started to see the transit system deteriorate.

“You would have less trains running. They would break down,” Hernáiz said.

“Once, I was going to the university, and then the train just stopped and the lights went off. This is full of people, right? Everyone was as scared as I was.”

Musicians play instruments while sitting in the middle of a road littered with metro tickets at an anti-government roadblock in Caracas, Venezuela.

Venezuela’s hyperinflation also meant Hernáiz’s commute was getting more expensive, but his university job had a fixed wage that wasn’t keeping up with rising prices. When Hernáiz sat down and did the math, he realized his salary didn’t even cover the cost of his commute: He was losing money by going to work.

“That was a wake-up call,” he said.

In cities across the country, including Caracas, flatbed cargo trucks called perreras, meaning “kennels,” have replaced some of the abandoned bus lines, according to Hernáiz. But these trucks don’t have basic safety equipment. Passengers fall off, and the trucks overturn. The National Assembly reported that in a three-month span in 2018 at least 39 riders were killed and 275 injured on perreras.

A staffing crisis compounds all of these problems. The U.N. Refugee Agency estimates that 7.3 million people have fled Venezuela from 2014 through 2023, more than 20% of the population.

“You’re losing a lot of engineers,” Kingsbury said. That makes it even more difficult to maintain the system.

According to Kingsbury, as the service gaps in the transit system widened, local officials in wealthier parts of Caracas began organizing bus services within their districts that didn’t extend to other parts of the city.

Transit infrastructure in Caracas, already a web of private and public networks, fractured.

Hernáiz thinks that the transit system started to improve marginally after 2018, but that its collapse still indirectly contributed to some Venezuelans’ decision to leave the country.

“If you can’t get to work and this starts to impact your economic viability, then you start to suffer,” he said.

Why the CTA probably won't collapse

Though the CTA cuts could lead to a negative feedback loop, it isn’t necessarily a death spiral or a one-way ticket to system collapse.

“We have more social, economic, and political stability,” Lowe said.

In addition, she said Chicago is less reliant on coordinating small, informal operators. Plus, Chicago’s heavy rail infrastructure gives it a unique advantage: It’s faster than driving in heavy traffic.

“We have infrastructure in place to get people places fast,” Lowe said. “Even if every bus rider suddenly got a car or took a Lyft everywhere, the L would still be competitive.”

While the CTA isn’t likely to collapse, the funding gap remains a challenge. A CTA spokesperson told ChicagoGlobal that “neither fare increases nor service cuts will fill the anticipated annual budget gap…which is currently estimated at $500 million and growing.” Regional transit agencies are collectively lobbying state and local officials for “new, long-term funding solutions.”

After the Illinois General Assembly asked the Chicago Metropolitan Agency for Planning to recommend fixes to the $730 million budget gap, the agency suggested that the legislature increase state funding for transit in northeastern Illinois.

Chicago Metropolitan Agency for Planning noted that CTA, Pace, and Metra receive a lower level of state funding than other peer transit systems, including those in Los Angeles, New York, and D.C. The agency also recommended tying fares to inflation so that revenue keeps up with costs.

“We’ve seen crises after crises in our public transit system, and hopefully we can have a conversation about sustainable funding so that we can have the system that we deserve,” Lowe said.

This story first appeared in the ChicagoGlobal newsletter, a joint project of Crain's Chicago Business and the Chicago Council on Global Affairs.