Polling data shows that although Americans believe that Russia is acting to contain US power, the US public favors cooperation and engagement rather than containing Russia.

A breakdown in cooperation between the United States and Russia in Syria, disputes over bilateral arms control agreements, and official US allegations of Russian cyber-meddling in the US presidential election have increased bilateral tensions. Most recently, the Kremlin ended participation in a joint agreement with the United States to eliminate both countries’ excess stocks of weapons grade plutonium. Yet even before these recent developments, increasingly frosty diplomatic relations seem to have taken their toll on mutual perceptions in public opinion.

New polling data from the 2016 Chicago Council Survey and the Levada Analytical Center in Russia—both independently conducted and funded—show that mutual perceptions between Russians and Americans are now at levels not seen since the Cold War. While there is common ground in public concerns about global threats, the surveys also show a great deal of mutual distrust. Russians express a sense of insecurity about US strength and influence, and prefer that their country aim to limit US international sway.

Key Findings

- Both Americans (72%) and Russians (52%) support their governments conducting airstrikes in Syria to achieve their respective objectives (for Americans, to fight violent extremist groups like ISIS; for Russians, to support Assad in his war against ISIS and the Syrian opposition).

- Russians think the goal of economic sanctions placed on their country was to weaken it (74%) rather than to stop the war in Ukraine, and 68 percent of Russians think that the deployment of NATO troops in the Baltic states and Poland is a threat to Russia.

- A sizable minority of Americans would support sending US troops to defend Baltic NATO members if Russia were to invade (45% in 2015), but only 30 percent say that Russia’s territorial ambitions are a critical threat to the United States.

A Rocky Post-Cold War Relationship

December marks the 25th anniversary of the breakup of the Soviet Union and the establishment of the Russian Federation. At one time this was perceived as a new opportunity to better US-Russia relations. And yet, some experts have recently begun to question whether or not we have entered a new Cold War.

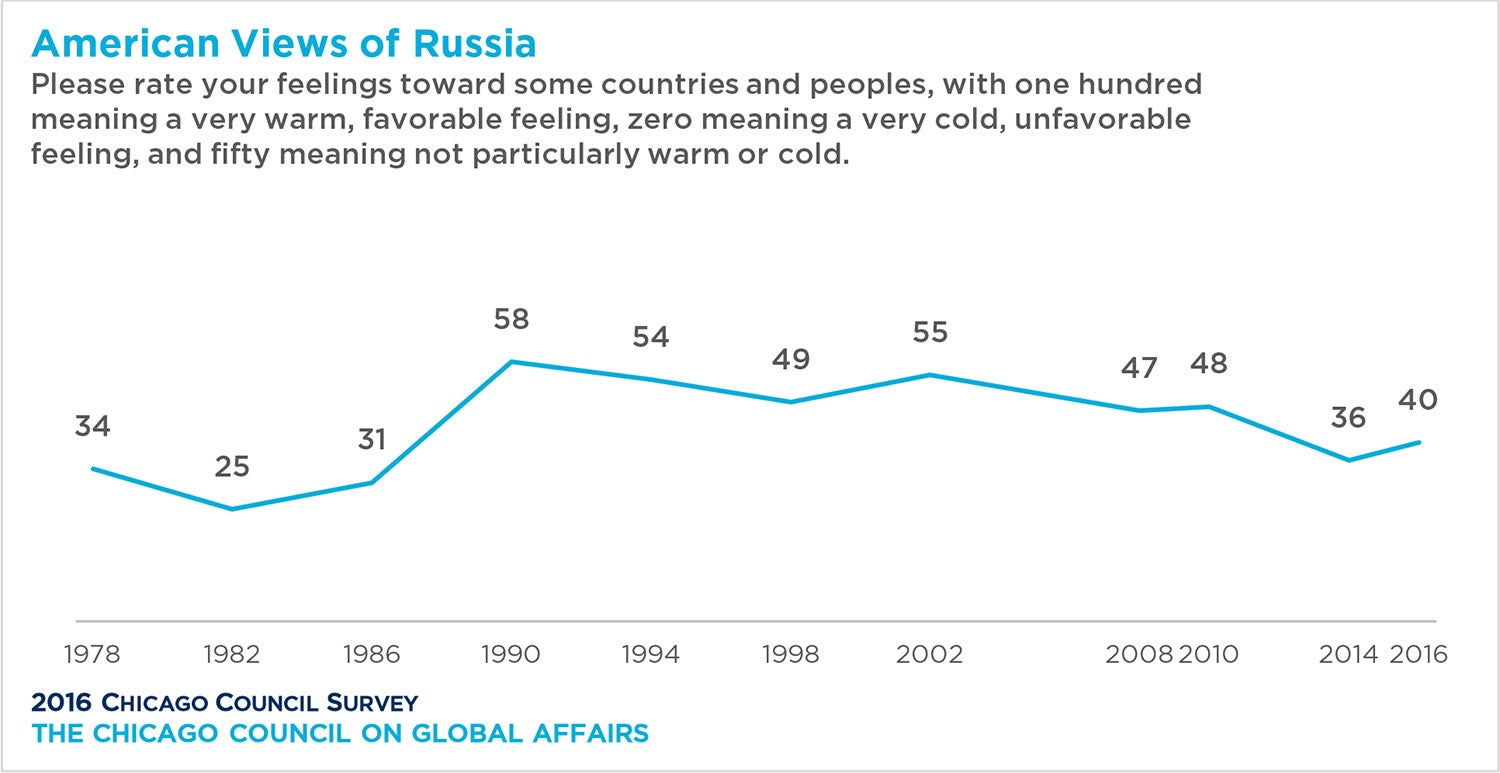

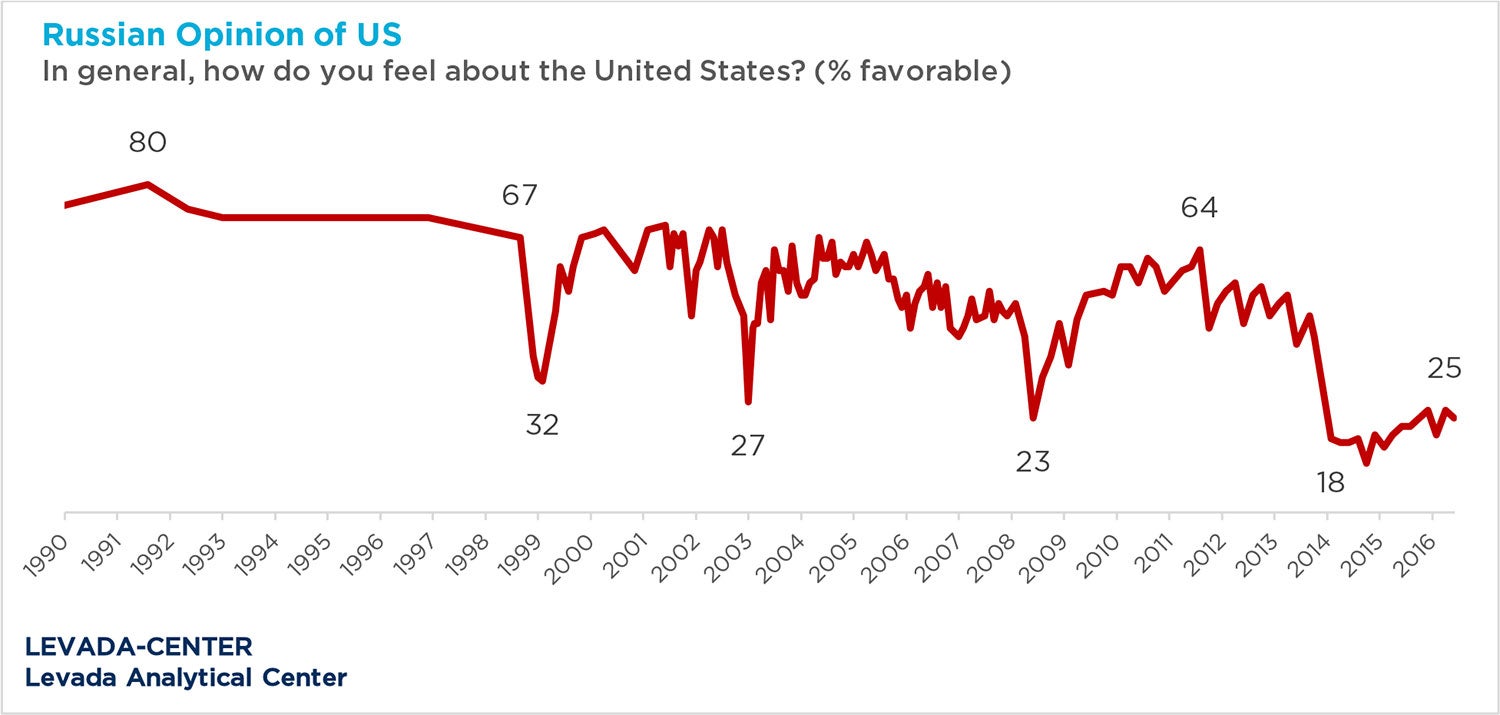

Neither Russians nor Americans view each other’s country favorably today. The chill in mutual perceptions settled in following Russia’s annexation of Crimea in March 2014 and its’ continued aid to pro-Russian rebels in the Ukrainian regions of Donetsk and Luhansk. Today the average American “feeling” toward Russia on a temperature thermometer scale is 40 degrees (from 0⁰ a very cold, unfavorable feeling, to 100⁰ a very warm, favorable feeling). Similarly, only 23 percent of Russians say they have a positive view of the United States. And a majority (55%) of Americans feel US-Russia relations are worsening, a view more common among Republicans (61%) than Democrats (51%).

The Chicago Council Survey trend on American feelings towards Russia goes back to 1978, when the United States and the Soviet Union were locked in a Cold War struggle. During the Cold War years, Americans gave the Soviet Union an average temperature rating between 25 and 30 degrees (1978-1986). From 1990 to 2002 the temperature remained in the mid to high fifties. The average temperature rating began to dip again in 2008, a few months after the Russian-Georgian conflict over South Ossetia, fell further after the Russian annexation of Crimea in 2014.

The Levada Center’s results show that Russian views of the United States may be even more responsive to global events, in part due to their more frequent polling. Trends since 1990 show four major downturns in public opinion of the United States: in 1999, 2003, 2008, and 2014. The first two dips are likely in response to US actions abroad, including US involvement in NATO’s airstrike campaign against Serbia and the invasion of Iraq. Both downturns reflect Russians’ generally critical view of US engagement abroad. A March 2016 Levada poll found that 76 percent of Russians say they disapprove of the US approach to international problem solving. The current drop in relations is the longest lasting that Levada Center polls have registered.

The other two major downturns are likely reactions to official US criticisms of Russia’s handling of the conflict in Georgia and Ukraine’s Euromaidan revolution and eventual Russian annexation of Crimea. While the United States and several European countries objected to Russia’s actions in Ukraine, Russians felt differently: a spring 2015 Pew poll found that 83 percent of Russians approved of the way Russian President Vladimir Putin handled relations with Ukraine. In the same survey, 61 percent of Russians agreed with the notion that there are parts of neighboring countries that belong to Russia.

Russians also view the Western sanctions placed on Russia after the annexation of Crimea cynically. Levada found in October 2016 that the majority of Russians think the goal of the sanctions placed on Russia was to weaken it (74%), rather than to stop the war in Ukraine (6%) or restore a geopolitical balance disrupted by the annexation of Crimea (17%). Two in three Russians believe that Russia should not seek a compromise with the West in the face of sanctions, but should ignore the sanctions placed upon them (65%). Six in ten Russians also believe that they should outright ignore Western criticisms of Russia (59%).

Distrust at the Heart of the Freeze

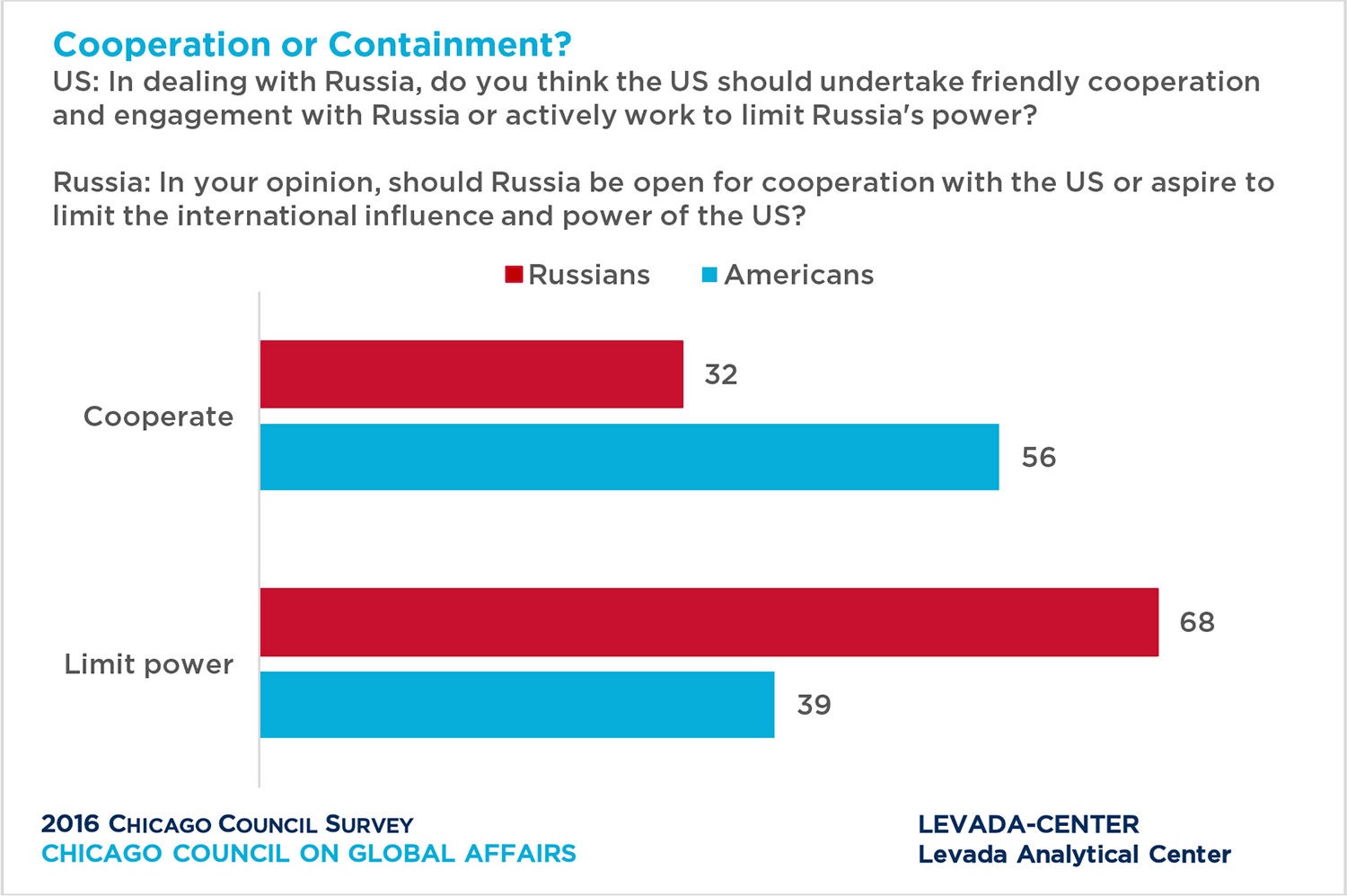

While Russians think their country should work to contain US influence abroad. Americans would like the United States to cooperate with Russia. Seven in ten Russians think Russia should focus on limiting US power and influence (68%), compared to a third who favor cooperation with the United States (32%).

For their part, a majority of Americans say that in dealing with Russia, the United States should undertake friendly cooperation and engagement (56%) rather than actively work to limit Russia’s power (39%). Democrats are 12 percentage points more likely to favor cooperation than Republicans (62% Democrats, 50% Republicans). In addition, despite Donald Trump’s relatively open views toward cooperating with Russia, his core supporters feel no different than Republicans overall (47% of core Trump supporters support cooperation).

The American public overall is skeptical of Russian reciprocity. Seven in ten (71%) Americans say that Russia is actively working to limit US power versus one in four (24%) who think it is trying to cooperate and engage with the US. The American public also has concerns about Russia’s international role: the 2015 Chicago Council Survey found that just 43 percent considered strong Russian leadership in the world desirable, and only 27 percent were confident in Russia’s ability to resolve problems responsibly. There were no significant partisan differences.

Influence and Threat Levels

Russian and American public opinion also diverges over the level of influence and threat each perceives from the other country. In 2016, the US public rates Russia a 6.2 out of 10 in terms of global influence, behind the US (8.5), China (7.1), and the EU (7.0). These opinions are not new; American views of Russian influence have remained stable over the past 10 years. While Russians agree that the United States is the most influential country, they rate Russia as the second most influential nation in the world (7.7). In Russians’ estimation, this puts Russia above other major global powers such as China (7.1) and the EU (7.0).

Americans Do Not Worry about Russia’s Territorial Ambitions…

As a threat, only a third of Americans say that Russia’s territorial ambitions represent a critical threat to the United States (30%), consistent with previous Chicago Council Survey results. Americans rate Russia’s territorial ambitions below other threats including climate change (39%) and China’s military power (38%), and far below Americans’ top two perceived threats in the form of nuclear proliferation (61%) and international terrorism (75%).

Although cyberattacks were not an option in the 2016 Council Survey, in 2015 Americans ranked cyberattacks on US computer networks as the second greatest threat to the United States (69%, tied with international terrorism). This threat perception could be greater today given Russia’s alleged leaking of hacked emails related to the US presidential election, which Russian President Putin recently denied.

…But Russians Worry about US Intentions

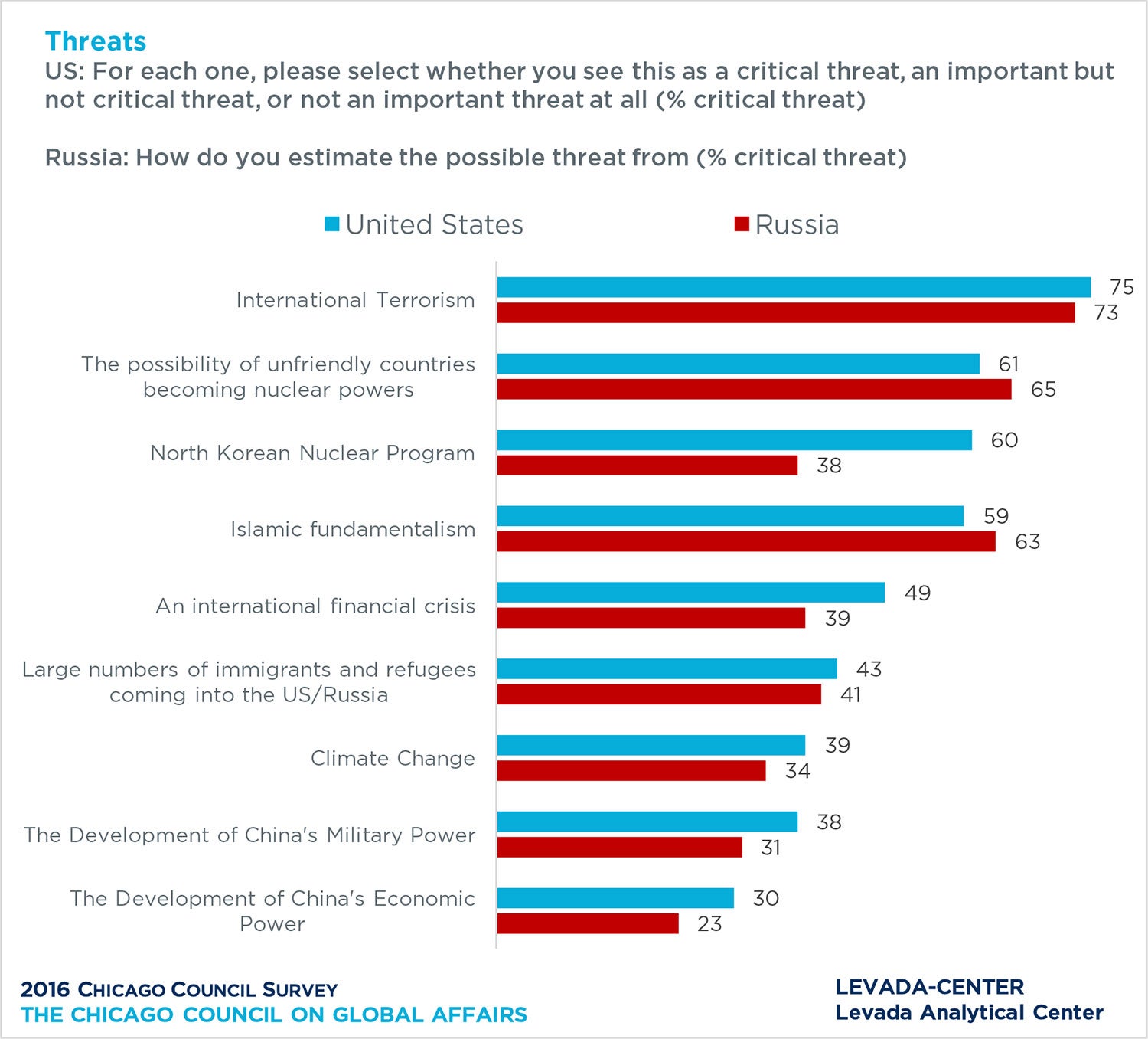

Conversely to US impressions of Russia, a majority of Russians (56%) see US ambitions to exert control over other countries as a critical threat to Russia. This threat was ranked fourth, below Islamic fundamentalism (63%), nuclear proliferation (65%), and international terrorism (73%).

NATO Complicates US-Russian Relations

NATO is often pointed to as an obstacle in US-Russia relations, as the alliance was formed partly to contain the Soviet Union’s expansion and limit its influence in Europe. Russian leaders were particularly upset when NATO expanded its membership to the Baltic nations in 2004, just at the western border of Russia.

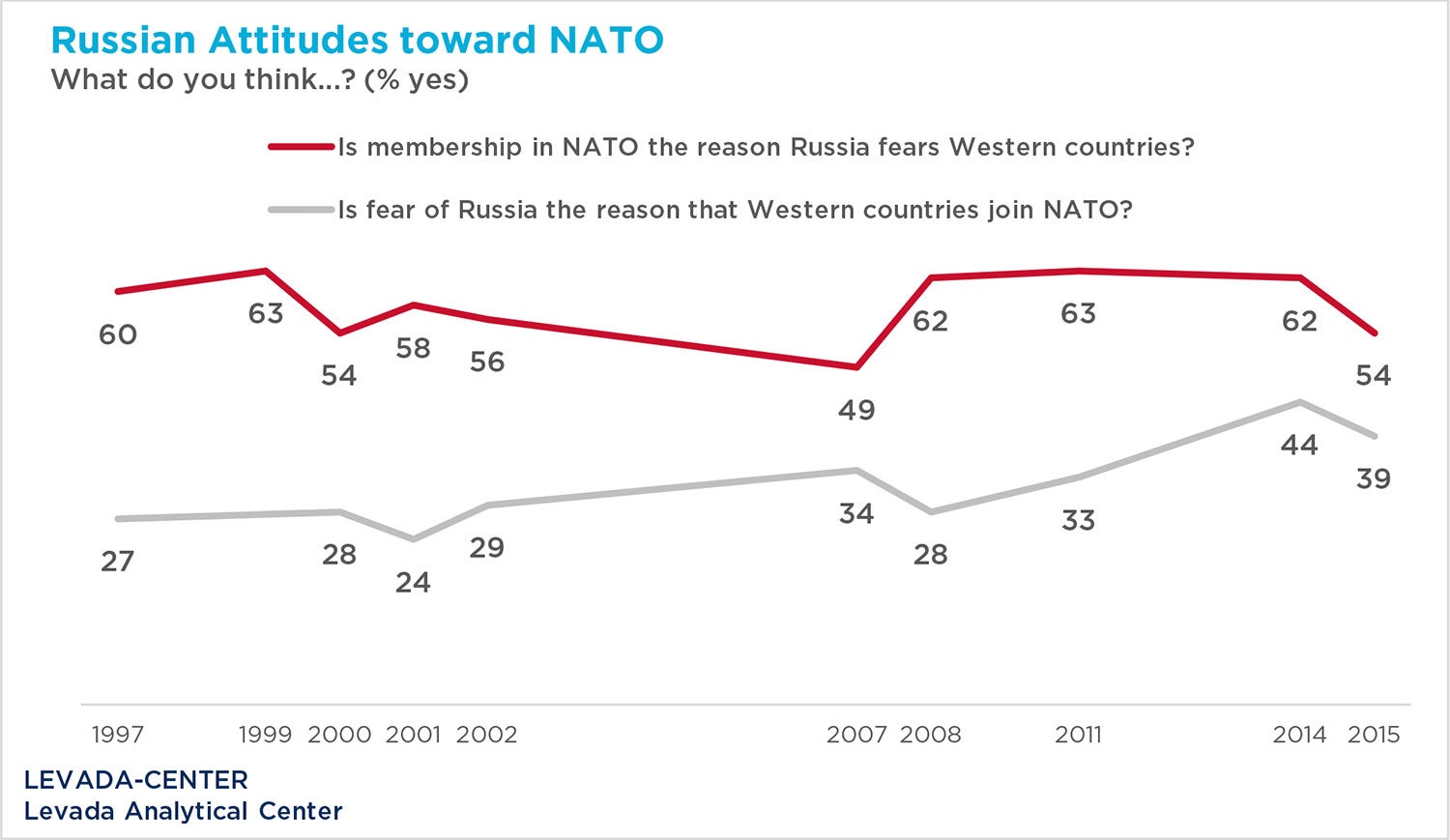

From the Russian viewpoint, NATO enlargement continues to represent a threat. According to a June 2016 Levada survey, 68 percent of Russians think that deploying NATO troops in the Baltic states and Poland is a threat to Russia, and 64 percent are concerned with the possibility of Ukraine joining the alliance. A 2015 Levada survey shows that among the public, a narrow majority (54%) say that Russia fears Western countries because of their membership in the NATO alliance, although this threat perception has declined since 2008.

Only a minority of Russians continue to think Western countries join NATO primarily because of fear of Russia, though more believed so in 2015 (39%) than between 1997 and 2011.

Americans are similarly hesitant to face off in a conflict with Russia. The 2014 and 2015 Chicago Council Surveys found that if Russia were to invade a NATO ally such as Lithuania, Latvia, or Estonia, sizable minorities of Americans favored the use of US troops in response (44% in 2014 and 45% in 2015). Fewer favored using force if Russia invaded the rest of Ukraine (30% in 2014, 31% in 2015).

What Should Be Done in Syria

One of the major points of contention between Americans and Russians has to do with each country’s involvement in Syria. Americans are most supportive of actions specifically targeting the Islamic State and less supportive of actions that might ensnare American troops in Syria’s civil war. The 2016 Chicago Council Survey shows that majorities of Americans support conducting airstrikes against violent Islamic extremist groups (72%), sending special operations forces into Syria to fight violent Islamic extremist groups (57%), and enforcing a no-fly zone over parts of Syria, including bombing Syrian air defenses (52%). Four in ten Americans favored sending combat troops into Syria to fight violent extremist groups (42%). Smaller minorities favored accepting Syrian refugees into the United States (36%) and helping to negotiate a peace agreement that would keep Assad in power (31%).

During his speech to the United Nations in September 2015, President Putin justified Russian intervention in Syria because of a need to confront ISIS and other terrorist groups. In a November 2015 Levada survey, a plurality among the Russian public said they sympathize with neither side in the conflict in Syria (44%). Only a quarter of the Russian public said they sympathize with Assad (26%), but a full half said that Russia should nevertheless support Bashar al Assad in his war with the Islamic State and the Syrian opposition (50%, vs. 23% saying Russia should take neither side, and 7% saying Russia should join the western coalition in the war against the Islamic State and the regime of Assad).

As far as their own government’s goals, Levada results from March 2016 show that six in ten Russians believe that their leaders’ main aim is to neutralize and eliminate “the threat of military action by Islamic radicals and terrorists spilling over into Russia” (58%). Sizable percentages also think that Russia’s leadership is working to defend Assad’s regime in order to prevent a series of “color revolutions provoked by the United States around the world” (27%), and “asserting the economic interests of Russian companies in the Middle East” (19%). No more than one in ten Russians say that their government’s actions in Syria are intended to support the Assad regime “in its fight against the opposition to prevent similar anti-government protests in Russsia” (9%), to fracture the Western coalition [against Assad] “in order to prevent Russia’s total isolation and harsher sanctions” (9%), or to distract the Russian population from “the economic crisis, authorities’ incompetence and inability to deal with problems and corruption” (8%).

A just-completed October 2016 Levada Center survey finds that a majority of Russians support the Russian airstrikes in Syria (52%), but only 49 percent of Russians say that Russia should continue to interfere in the Syrian conflict. In 2015, Levada’s poll found a majority of the Russian public supported giving political and diplomatic support (74%), military-technical support in the form of consultations and arms (62%), humanitarian aid (59%), and direct military support in the form of airstrikes (54%). Nearly half favored providing economic aid (48%). Similar to Americans, only a minority of the Russian public favored sending ground troops to Syria (19%) or admitting Syrian refugees and giving them aid (24%).

Areas for Cooperation

Despite the current breakdown in cooperation in Syria, the two states have engaged in pragmatic cooperation on matters of international security. US Secretary of State John Kerry said in a talk at the Council on Global Affairs that the United States should continue to cooperate with Russia because, “without them being part of the solution, they are part of the problem.” In recent years the two countries have engaged in counterterrorism cooperation, worked together (with the United Kingdom, France, China, and Germany) to negotiate the Iranian nuclear deal, and brokered the dismantlement of the Assad regime’s chemical arsenal.

Though the American public say they are willing to cooperate with Russia, the Council’s 2016 poll shows that Americans think the United States and Russia are working in different directions on a number of issues, including ending the conflict in Syria (64%), limiting Iran’s nuclear program (58%), and reducing nuclear weapons worldwide (59%). This is telling of American distrust and/or lack of awareness, since Russia played a positive role in the negotiations with Iran—both countries oppose a nuclear Iran—and the US and Russia have a history of cooperating on nonproliferation that dates back to the 1950s.

Levada’s October 2016 poll found that Russians are somewhat divided on the possibility of finding a common language to solve the Syria problem with 35 percent saying it is possible versus 39 percent saying it is impossible. Almost half of Russians are afraid that a conflict resulting from disagreements between Russia and Western countries on Syria may result in a third world war (48%). This likely reflects the anxiety over devolving Russia-US relations rather than a perception of a real threat.

Americans and Russians have similar security concerns which should increase instances of cooperation. Both Russians and Americans see international terrorism and nuclear proliferation as the first and second most critical threat to their countries. Islamic fundamentalism was the third most critical threat to Russians and fourth to Americans. Counterterrorism and nonproliferation are two areas in which the United States and Russia can put aside differences to work together.

Russians and Americans are similarly less concerned about immigration, climate change, and the rise of China. Fears of North Korea are high among Americans, but not as much of a threat to Russians.

Hope for the Future?

There appears to be greater trust and openness from younger Americans and Russians, namely those who grew up in the post-Cold War world. Both Levada Center and Council polls found slight increases in favorability towards each country amongst young Russians and Americans.

Levada found that compared to the other three age groups, their youngest was significantly more likely to have favorable feelings and demonstrate a willingness to cooperate with the United States (see table below). While young Americans did not average a warmer feeling towards Russia, they were more likely to support increased cooperation with Russia and were significantly less threatened by Russia’s territorial ambitions. Yet while a majority of young Americans want cooperation with Russia, even among the young Russians, a majority still favored limiting US influence. What’s more, young Russians are just as likely as other ages to sense a threat from the United States.

US Methodology

The analysis in this report is based on data from the 2016 Chicago Council Survey of the American public and US foreign policy. The 2016 Chicago Council Survey was conducted by GfK Custom Research using their large-scale, nationwide online research panel between June 10-27, 2016, among a national sample of 2,061 adults, 18 years of age or older, living in all 50 US states and the District of Columbia. The margin of sampling error for the full sample is ±2.38, including a design effect of 1.2149. The margin of error is higher for questions administered to a partial sample and among partisan subgroups.

Partisan identification is based on respondents’ answer to a standard partisan self-identification question: “Generally speaking, do you usually think of yourself as a Republican, a Democrat, an independent, or what?”

“Core Trump supporters” are those in the sample who said that Donald Trump was their “top choice for president” among a list including the following candidates: Hillary Clinton, Donald Trump, Bernie Sanders, Jeb Bush, Ted Cruz, and John Kasich.

The 2016 Chicago Council Survey is made possible by the generous support of the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation, the Korea Foundation, and the personal support of Lester Crown and the Crown family.

Russia Methodology

The Russian part of analysis in this report is based on data from several all-Russian surveys conducted by Levada-Center (Levada Analytical Center). The surveys are done as face-to-face interviews in the home of respondents. The representative sample includes urban and rural population of Russia, 1,602 persons aged 18 years and older, living in eight federal districts of the Russian Federation. Inside each district the sample is distributed among five strata of settlements proportionally to the number of population living in them in age of 18+ years. All cities with over 1 million population are inserted in the sample as self-representative units. The margin of error ranges ±1.5 to ±3.4 percentage points, depending on the specific question.

The surveys are initiative-based research projects that were done at the Levada-Center’s own expense.

About the Levada-Center

Levada-Center is one of the leading research organizations in Russia that conduct mass public surveys, expert and elite surveys, depth interviews, focus groups as well as other survey methods. Staff of the center brings together experts in the field of sociology, political science, economics, psychology, market research, and public opinion polls. Polling results and expertise of the Center’s staff is broadly covered by national and international media such as Kommersant, Vedomosti, RBC, The Economist, The Wall Street Journal, The New York Times, Reuters, BBC Radio, Radio Liberty, and others. Learn more at levada.ru and follow @levada_ru or on Facebook.