Biden's Human Rights Promises: Rhetoric or Real?

Play Podcast

Play Podcast

About the Episode

On Deep Dish, we explore whether the Biden administration has followed through on its promises to prioritize human rights in US foreign policy and whether recent events like the release of the annual human rights report and the Democracies Summit provide any hints about how effective they have been. Join experts Steven Feldstein and Sarah Yager as they evaluate the administration’s progress and unpack ways the United States can do better abroad.

[Lizzy Shackelford: INTRO: This is Deep Dish on Global Affairs, going beyond the headlines on critical global issues. I'm your host, Lizzy Shackelford with the Chicago Council and Global Affairs.

From the outset of this administration, President Joe Biden and his Secretary of State, Anthony Blinken have said time and again that human rights is at the center of their foreign policy.

This was intended to be a shift not only from the Trump administration, which openly dismissed a values-based foreign policy, but also from a history of US foreign policy that has long overlooked human rights.

But as Biden's promise shift really played out today, we're delving into what it would mean to put human rights at the center of US foreign policy.]

Our guests to discuss this are Sarah Yager, the Washington Director at Human Rights Watch, where she leads the organization's engagement with the US government on human rights issues around the world. Welcome to Deep Dish, Sarah.

Sarah Yager: Thank you. Delighted to be here.

Lizzy Shackelford: And we have Steven Feldstein, a senior fellow at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. He was also the Deputy Assistant Secretary of Democracy, human Rights and Labor in the State Department under President Obama. And his research now focuses on technology and politics and the global context for democracy and human rights. Welcome to Deep Dish, Steve. It's so good to have you both here.

Steven Feldstein: Thanks for having me.

Lizzy Shackelford: I'd like to start with you, Steve, since you've led the state department's efforts on these issues from the inside before. Have you seen a real change under this administration and how it implements a human rights focus in our foreign policy?

Steven Feldstein: Yeah. Well, I would say there's a few ways to think about this. I think one is that if you compare this administration, the Biden administration to the last administration under Trump. There certainly has been a sea change and there's been a real commitment, to kind of pushing human rights back to the forefront, uh, of US foreign policy in pretty significant ways, including the just concluded Democracy Summit, and so in that sense, I think there's been a lot of really important moves. There's been a recognition of tech and democracy, an important executive order when it comes to prohibiting spyware, in the federal government. These are all really positive things. Not to mention, we can delve into the Ukraine War and what that means for human rights. I mean, I think a bigger question is probably if you take out the Trump administration and you sort of look at the general trend line of more regular administrations, does a Biden administration differentiate itself? And I think the answer there is a little more mixed. you know, certainly a lot of the relationships that we've seen with more problematic countries, like Saudi Arabia, history of human rights, violations are relationships that persist. And so, to that extent, I don't know that we've seen a significant break, but I would say by and large, there has been a push to elevate human rights as a more important consideration with US foreign policy, if not necessarily the primary consideration.

Lizzy Shackelford: Sarah, would you agree? What does this look like from an advocacy perspective?

Sarah Yager: I generally agree with Steve. We can talk about that Democracy Summit.

Lizzy Shackelford: I want to!

Sarah Yager: Yeah, sure. But I generally agree. I think the way that I, have been thinking about it is, so Biden and Blinken said that human rights would be central to US foreign policy. I think the way that that's turned out is that it is very central in their hearts. I don't disagree with the intent. How it plays out around the world in actual policy is really a lot more complicated and I think. the administration is willing to, let's call it, do human rights in places where it's easy to do that and where other US interests don't conflict. Where it's hard to do human rights. The administration is really sheepish about doing human rights. Where security interests are taking a more prominent role, where economic interests are taking a more prominent role, where great power competition comes into play. And I would say, you know, in the human rights community, none of us are naive enough to think that human rights would be the priority. I appreciate the centrality. In the remarks that are coming out of the administration, but when you look at the reality of actual policy, it's being balanced, in a sort of lower rung than I would have expected. In places where it's hard.

Lizzy Shackelford: Let's talk about the Democracy Summit. So this was the Biden administration's second Democracy Summit, and it was held just last month. What role does that play in putting values at the center of our foreign policy, and does it make us more credible or look more hypocritical on the world stage? Steve, what do you think?

Steven Feldstein: I think there's a lot of different ways to think about it. It's hard to sort of come out with like a uniform response. I think you can certainly nitpick, on a lot of the issues. And you can say that given the large number of countries which participate, it's some of which made very deliberate attempts at the end to kind of undercut or place reservations about their agreement with certain principles. India's a good case in point, but there's other countries as well. You can make an argument on the one hand saying, well, what did it do? what kind of norm setting are we accomplishing? On the other hand though, what has really struck me, are a couple things. One of which is that it has been an action forcing event to put out policies that otherwise would've taken a long time to do, whether it's different, groupings, to push on surveillance. Whether it's looking at, ways in which to prohibit certain types of malicious technologies from being used to undercut human rights activists. Whether it's getting money together, including some new money, to, you know, promote, democratic objectives. You know, I think the idea of using the summit as an internal action forcing event to bring to the forefront certain policies that otherwise would've languished or would've had been subsumed by conflicting priorities, I think has been a really important thing. And so from that end, I'm heartened that, there has been some momentum built despite, some issues that, people will, certainly recognize as being problematic.

Lizzy Shackelford: Sarah, do you see anything really positive coming out of the Democracy Summit?

Sarah Yager: So the Summit for Democracy was written about by candidate Biden on the campaign trail in Foreign Affairs in 2019. And I think as soon as he became president, his staff said, “Oh, dear God, we're actually gonna have to do this because he said that we have to do this.” and I don't think anyone wanted to do it. And the first summit came with all of the usual criticism about who's being invited and, you know, is all that kind of stuff. this second summit, I think I agree with Steven that it was an action forcing event, within the administration, but there's a bit of conflation between democracy and human rights with this administration. I think it was much more about democracy, showing that their intent was to show that democracy delivers for populations. There was very little on human rights and for the amount of time and effort that it takes to put on these kinds of events, I would've much rather have seen a bunch of effort go into rebalancing the Saudi relationship like President Biden said he was going to do or calling out, even if it's just behind the scenes, India and it's backsliding on democracy, there are all of these things that need to happen around the world and that attention and the human resources and time that it takes to actually improve democracies and human rights around the world was put into this event. Now, I do think that, I believe the people who are working on this, and they are very well intentioned and they worked really hard. I believe them that this was not just about the event, that it is about what happens now and I do hope that the US will continue to work with all of the democracies that attended this event to actually implement the commitments they made. But so far, certainly the human rights community, has been a bit morose about this summit.

Lizzy Shackelford: So one of the things that I noticed was that there was a lot more fanfare around the first, summit for democracies. This one actually almost snuck up on me. I didn't realize until it was almost game day that it was even happening. And I wonder what that means from the perspective of the government, does it mean, perhaps that, the administration's using it more as an internal mechanism, like you were talking about Steve, or, was it just that the shine was off by the time the second one came around?

Steven Feldstein: Well it's been a busy year, and there's been a lot of distractions for sure, and I think a second summit just naturally gets less attention in the news cycle than an initial inaugural one. The fact that it was also virtual, for the most part in terms of having leaders gather together, probably didn't help in terms of just getting attention as well. So I think all that is true. I do wonder if we didn't have such major issues like the Ukraine War right now and what's gonna happen with a potential spring counter offensive. And, you know, all these questions about weapon shipments and the depth of public support, that's really just sort of taking so much, oxygen and energy on the foreign policy end. I do wonder whether there would've been a little more of a push, but I also just think that follow up summits by nature, especially virtual follow up summits, are just not gonna get the same oomph that the first one would.

Lizzy Shackelford: I wanna shift to another, tool that the government has. One they've had for a lot longer than the Democracy Summit. The Human Rights Report, it's been around for almost 50 years at this point. They released the 2022 annual report just last month. This is something that as a former foreign service officer, I have written a few of these, penned them myself, so I know them quite intimately. But I wanted to talk a little bit about if this is a tool that this administration has taken a different approach to, or if there's anything we can glean from this year's report that, is indicative of this shift in approach on human rights. Sarah, I'll start with you. Just from the outside perspective, anything new or notable with this year's, State Department human rights reports?

Sarah Yager: I mean, if we look back at the Trump administration. We had some really big problems with the human rights report, including that, it just, didn't have the kinds of things on women and minority and LGBTQ issues that we wanted to see. Um, this administration is doing, I think, a great job with the human rights reports. I would also say it's probably about time to update this process. So the human rights report comes out once a year. And there's big fanfare and everyone reads through it to see like, is my pet human rights abuse in there and, is the US paying attention? And it's a good tool for Blinken to come out and say, we care about human rights and here are the things that we condemn. But I think for it to actually be useful to US policy makers, it should be an iterative report. So, if I'm sitting as a US policymaker and I'm thinking about an armed sale in July, then the human rights report came out in January. What is, what does that tell me about the human rights conditions in a particular country? It actually doesn't and I'm not necessarily thinking about, oh, how can I go pull that information because I'm thinking about the cost and the how we're gonna get the arms delivered and the blah, blah, blah. So it's about time for either Congress or for the administration to say let's make this an ongoing human rights conversation, and I'd be really interested. It's a lot of work, but I'd be really interested to know what Steve thinks about that since he's been on the inside of this.

Lizzy Shackelford: I will say the, former human rights officer for the State Department in me is just terrified by the idea of this being iterative and going all year round, but with the right resources, I'd have to agree with that sentiment. Steve, what do you think?

Steven Feldstein: Seems like that would be tough for the clearance process, from what I remember, but no. I mean, but, but you know, in theory, I agree. I've, been responsible. I didn't, write, any human rights reports, but I was certainly responsible for clearing and editing numerous ones, particularly for Sub-Saharan Africa. And it is a bear, especially when you kind get to the four or five countries where there are internal disputes about what one can say, and you have to arbitrate those, at different levels. I mean, that is, that is hard. And I think, there's this, conundrum. Cause I think Sarah is right in the sense that. Like, let's be honest, not only are human rights reports fairly static, but there is a natural time lag that's built in. So even when they come out, whenever, it always varies a little bit. Let's say it comes out like in February or March, right? You know, it's not as if it reflects what came out, like what happened up through January. It actually reflects sometime much earlier in the prior year and so, end up, by the time it gets out, you end with like a three quarters of a year lag between what actually has happened and where you currently are. And so it's useful as A point in the record, it's something you can point to if you have testimony, if you're trying to, get backup for criticizing the regime in, let's say Rwanda. You know, you can look to the human rights report and say, this is what the State Department has officially set. That's great. But in terms of having something that's updated or iterative or specifically useful for inputting in an ongoing live interagency process when it comes to like arm sales. Uh, not so much. And so then that's where you need, at least the internal updating. And so in that sense, there is less of an applicability, as a result of that, so that's a structural problem and that's hard to get around.

Lizzy Shackelford: I will say as, the primary author for the South Sudan report in 2013 when war broke out two weeks before the end of the year, after we had already gone through most of the clearance process. Yes, I can say that process is an obstacle to having real time information, but that raises a different question though for me, is the human rights report, the most useful tool that we could use to lead up democracy, rights and labor? Steve, do you think there's a different way or a different approach, that we could do to help put human rights more actively in the foreign policy process?

Steven Feldstein: Yeah. You know, look, I think this human rights report is a tool and I think it's useful and that it forces conversations that can be unpleasant, particularly for countries that aren't always in the interagency spotlight. and so having that out there and, achieving consensus and getting on the record, what the US perspective is, on a country's record, on a kind of yearly basis is really critical. I mean, to me it's like a necessary, but it's not sufficient when it comes to what you could actually do. I would say the number one thing that helps human rights is to give room at the interagency on the issues that matter to a DRL person. that to me was always the struggle or the thing that I always fought for when I was in the administration, you know, whether it's, looking at arm sales in Nigeria, looking at, different piece processes in relation to Sudan, or thinking about, our relations to Ethiopia. The most important thing I could do would be to have a voice at the table, whether it was a larger group or a smaller group, and to be able to represent the equities from a DRL perspective and how those heard. Now, even if I didn't win out, at least to be given a fair hearing for those issues was critical and so to the extent that is something that can continue to happen and that maintained. To me that matters more than almost anything else when it comes to actually advocating for these issues in the decision making, convenings that occur.

Sarah Yager: I have an idea, I'm going to pitch it here, on Deep Dish, and I am positive that Avril Haines, the director of National Intelligence, listens to this podcast and we'll take this idea and run with it. I shouldn't say this. As a human rights watch person, our whole goal is to name and shame, right? So we want things to be public and there's a real worth in that. But I think my interest is in seeing US policy makers, like what Steve was just talking about, have the information on human rights so that if we're gonna say that human rights essential to us foreign policy, okay, put it on the table, and then balance it with security, economic trade, other interests. And the way to do that is for the intelligence community that the US has everywhere, to actually be paying attention to human rights. Currently, they do not, there is no training on human rights for agents and there is no directive from either the director of National Intelligence or the President to collect information on human rights. This includes things like civil unrest, what security forces might be doing in a particular country, those kinds of things. If they're abusing the population, for example, are canaries in the coal mines for instability, for coups. For all sorts of things that the United States should be very concerned about. And so what I would love to see is, human rights training absolutely for intelligence people, but also some sort of directive from the president that says, you must now pay attention to human rights. And you must collect that information when you are looking at, the environment in particular countries. and you could even put something at the CIA, you know, some small center to deal with this kind of thing. But I think that would give us policy makers a lot more information. Currently, they're not seeing the full puzzle.

Lizzy Shackelford: I love that idea, Sarah. And I'll say it, brings me to one of my questions, which is, one of the refrains we often hear is it's interests versus values. And that's one of the reasons it's like, you know, human rights is important, it's a value of ours, but when it comes up against an interest like security, it tends to lose out. I'm certainly of the perspective that human rights are an indicator of, how our interests in different areas are going to play out. But that brings us to the question of how should we put human rights in our foreign policy, and what role should it play?

Steven Feldstein: Yeah, I mean I think that has always been. constraint. It's not even that intelligence doesn't necessarily want to look at human rights oriented concerns is that there's always a struggle for resources, right? And there's always a million things that require the bandwidth of, different officers. And so to sort of say, look, amongst all the other priorities you have and things that you need to look at. One of those needs to be looking for the commission of atrocities or looking for, other human rights, potential violations, and to incorporate that into, different products that come out. I mean, oftentimes, what do we know, from Washington, unless either informed by collection in one form or another, or, through reporting from embassies. And so that definitely helps to gin up the inter-agency process when it comes to ultimately what types of meetings will be convened, what decisions will be made and what kind of responses will occur. So I do think that helping to, choose that side up more could pay a lot of divides.

Lizzy Shackelford: Steve, you've been involved in those interagency conversations. What do you think would get them to pay more attention to human rights related issues?

Steven Feldstein: I think one thing you talked about was this sort of, interest versus values, that, people oftentimes, I think it's a sort of a false dichotomy to be honest. And I think that interest and values, mutually compliment one another. And so, when you look at practices that directly get at some of the structural issues, so let's say you're working with Armed Forces partner, oftentimes the most, relevant information we would hear would be coming up from, organizations like Human Rights Watch, as opposed to internally. And then the next thing that happens, it's not that, information is taken at face value. Instead, there's this long drawn out process where it's sort of questioned whether, is this report credible? What does that mean? Let's investigate that. Let's get someone to come in on the ground and look more into it. And so, you end up taking another eight weeks, especially if it's of an issue affecting a major policy concern where you're just fighting about whether the information itself is something that can be used. So finding a way to kind of get at that so you can actually achieve quicker consensus about what has occurred, and then jump to, the next step, which is, well, what do we do about it? I think would help, quite a bit.

Lizzy Shackelford: I'm gonna shift over to, something getting at that kind of interest first values perspective here. It's pretty clear today that great power competition is really the foreign policy driving force for our decisions today. And I've heard arguments that invoke this both in the defense of centering human. More in our foreign policy and against it. Some people think it strengthens our case to only work with countries that share our values. Others think that this approach means that we're just handing up ground to China. I'm curious what both of you think about how the framing of global competition as democracies versus auto autocracies has impacted the role that human rights play.

Sarah Yager: I have to say I'm not big on this autocracy versus democracy stuff and people in my, human rights community do it all the time. I think we've bought into it. But there are plenty of places around the world where if you look at the human rights abuses, or where governments are standing up for human rights, it doesn't actually fall neatly into this black and white autocracy versus democracy world. And to go back to what Steve was saying, in past administrations we have made the point that human rights is part of national security. You can be more stable if you are working on, actually promoting human rights and democratic values. At the moment, we are back to square one in trying to make those arguments. I don't know what happened to them, but with this administration, consistently what we're seeing is human rights is a nice to do, but not an imperative when it comes to these other interests. And if you're gonna look at the world as autocracy versus democracy, how can you not say that human rights is the litmus test for which bucket you're falling into. it's a spectrum around the world. It is not so cold war. President Reagan used human rights. He never wanted to do human rights. He didn't like human rights. He said, we're not gonna have a human rights policy. Then he realized that human rights was this really great tool that he could use at least rhetorically, to set America apart from the communists. President Carter did almost the opposite, where in fact, so much of what he cared about was human rights, and he didn't necessarily talk about it. He did things like creating a human rights working group in the interagency. You know, these were things that had day-to-day ramifications, for really promoting human rights within US policy making. And what we're currently seeing is every conversation I have is about China. It doesn't matter whether the place I'm talking about or the human rights abuse I'm talking about has anything to do with China, China will come into the conversation. My community is trying to figure out, do we lean into this and say, okay, let's try to use human rights somehow to get into this conversation and, promote it? Or do we say, this is a false construct?

Lizzy Shackelford: Steve, what are your thoughts on the Great power competition, framing of all of this?

Steven Feldstein: I think, first of all, I, been uncomfortable from the very beginning about the sort of democracy versus autocracy framing. I don't think the world is structured that. and I think that we should be much more nuanced in terms of how we approach these issues. I think there are a certain number of countries where when it comes to the great power competition model, I think we have to be very careful about how we engage with them and they should be very limited. Saudi Arabia, you know, is the type of country that represents that to me. But then I think there's a whole other slew of countries that have problematic records, but where I think there's also leverage to engage and do things with them. Take a country like the Philippines, which is marginally better now than it was under Duterte, but still has a very problematic record. Take a country like Thailand, which again has been doing many anti-democratic things, but there are ways you can work with civil society to help build pressure. I think to just simply say you're either in this bucket or that, and everything, relates to China, by the way, I think both is reductive, and doesn’t adequately reflect the nuances of the different countries that we're dealing with and the variety of incentives and motivations they have, and how if we push the right levers, we can actually bring about, a greater capacity for change, than otherwise. But, I'm really concerned about this sort of rush to, get into a second cold war, with China and to use as a frame for anything, just as Sarah mentioned, that really is to our detriment and there are places and contexts where, countering China strategically is in incredibly important. And I think there are many areas where it is a distraction or it is used as a proxy to push other issues. And I think we have to be careful about that. I mean, the world is not simply a place where it's just US, China and everything else. And frankly, if you talk to leaders and individuals and citizens in different countries, they'll say the same thing. They'll say the China issue is one of many things out there, so don't turn it into that. Cause I think it undermines our own message anyway.

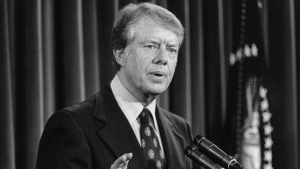

Lizzy Shackelford: It is rather reductive and unhelpful. Sarah, since you brought up Jimmy Carter, I'd love to wrap this conversation up talking a little bit about his legacy, because of course he was, as you say, the first, president to really bring human rights officially into our foreign policy. I'd love to hear from both of you, just your thoughts about the legacy that his administration left, how useful those tools are today. And, if there is a more productive way that we could build on some of the structures that he put in place in US foreign policy in order to find that right balance of bringing human rights in.

Steven Feldstein: I think it's a bit of a complicated legacy, when it comes to President Carter. I mean, I think certain. Many of the structures that are in place now did not originate, during his presidency, including, the bureau that I served in authorized by Congress in that, period. Um, and I think like, you know, you need to have structures in order to give a place in which to then push for these issues. And so the idea of even having a seat at the table is only something that's possible when you have the capacity to, to lobby for and advocate for a seat to begin with. And so I think, foundationally what Carter left is really kind of an important blueprint for how to do this, how to elevate this. There is criticism that Carter fell short and that in subsequent administrations, there was a, sort of decisive or explicit focus on not following Carter's legacy and pursuing a more muscular, a perceived stronger, legacy. And that there's been this conflation unfairly that, if you stand up for human rights, that's sort of weak. And it comes at the interests of more dominant foreign policy, economic interests, security interests and so forth. And I think that often can be a struggle. I don't think it's true, but I think that there is this sort of stereotype internally where it's like, well, you belong to the feel good, fuzzy, nice issues. The, not have to do issues, not need to do issues, but the nice to do issues. And I think finding a way to bring that back into more of a cohesive hole that human rights is part of national security is related to, preserving and advancing US interests as much as is a sort of universal set of principles is critical and something that I think still, still remains an uphill battle.

Lizzy Shackelford: Sarah, you're the advocacy community often comes at it with a less nuanced approach, but I think that you've shown that you've got, a bit of one that really does fit in with what works in foreign policy. What are your thoughts on, both Carter's legacy and, how best to place human rights in our foreign policy?

Sarah Yager: What Steve just said, was really interesting to me and it kind of triggered, I'm gonna say triggered like as in trauma something, which is that human rights is sort of seen as rainbows and puppy dogs and this nice thing to do. Look, I worked for Samantha Power when she was the US Ambassador to the United Nations. Nobody looks at her and says, oh, isn't that sweet? You know, she's doing this human rights thing when it comes to President Carter's legacy, nobody looks at National Security Advisor, Brazinski or Warren Christopher, Secretary of State as oh, that was so sweet that they did human rights. No, they actually really cared about it. And they cared about it, on their own. And because President Carter had that sort of command environment as they call it in the military, where he said, this is something that I am basing my legacy on, and you are going to care about this. And what I love about what they did, it was not a summit, it was not a big event. It was not showy. It was, gimme a working group any day of the. Give me a memo, a directive from the president that says, this is what I care about. They came up with a human rights strategy and plan. Those are all things behind the scenes, but they really made an impact. And of course, President Carter, you saw that he really cared about this because he devoted his entire post presidency to getting at the human rights issues where it is hard to do. If you really care about human rights, you don't just focus on the easy places. You go to Israel in Palestine, and that's exactly what he did, and he's taken a lot of flack for it. But that's a little bit more of what I'm hoping to see from this administration. Take on the hard stuff.

Lizzy Shackelford: Sarah Yager of Human Rights Watch and Steve Feldstein of the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. Thank you both for helping us understand how we can better address human rights in US foreign policy.

[Lizzy Shackelford: OUTRO: And thank you for tuning in to this episode of Deep Dish!

A reminder that we wanna hear more from you, our listeners, so send us an email or better yet, a voice memo to deepdish@globalaffairs.org -- You can suggest issues you'd like us to cover, guests you'd love to hear from, or you can just let us know how you think we're doing.

And if you're looking for more deep dish in your podcast diet, tap the follow button in your podcast app and you'll get each new episode as it's released. And if you think you know someone who would like today's episode, please share it with them!

As a reminder, the opinions you heard belong to the people who expressed them and not the Chicago Council on Global Affairs.

This episode is produced and edited by Kyra Dahring and mixed by Frank McKearn at Aphorism Productions.

Thank you for listening. I'm Lizzy Shackelford and my co-host Brian Hanson, will be back next week with another slice of deep dish.]

2022 Country Reports on Human Rights Practices, Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights, and Labor, March 20, 2023

Related Content

US Foreign Policy

US Foreign Policy

"Carter sought to institutionalize human rights within our foreign policy decision-making structures, so that it would not only inform our foreign activities but constrain them as well," Elizabeth Shackelford writes.

Public Opinion

Public Opinion

In new Council polling, Americans say China’s treatment of minority groups isn’t just a question of internal politics.

US Foreign Policy

US Foreign Policy

With former US President Jimmy Carter in hospice, Elizabeth Shackelford joins the podcast to discuss his human rights legacy.