How Do Foreign Policy Experts Think About Allies?

A new experiment by researchers from the University of Illinois at Springfield, the University of Chicago, and the Chicago Council on Global Affairs finds that policy experts care about formal alliances. But even alliance relationships have limits.

While polls show that the Biden administration’s Afghanistan withdrawal is supported by a majority of Americans, some commentators, like the New York Times’ David Brooks, view it as an abandonment of our allies in Afghanistan.

The use of the term allies in this instance is interesting. American foreign policy experts often use the word loosely, given the variety of military partnerships and relationships maintained by the United States. Some countries have a formal defensive treaty with the United States, while others are merely recipients of US military financial aid. How do American foreign policy experts think of the term “allies,” and does variation in such thinking matter?

To find out, we fielded an experiment among US foreign policy experts/opinion leaders. Between October 2020 and January 2021, they contacted nearly 700 respondents who work in Congress, in various federal agencies that engage in international affairs, at foreign policy think tanks, and at US-based universities as international relations scholars. The goal was to understand whether the respondents would alter their policy preferences depending on how we described the various types of groups that could be characterized as an ally.

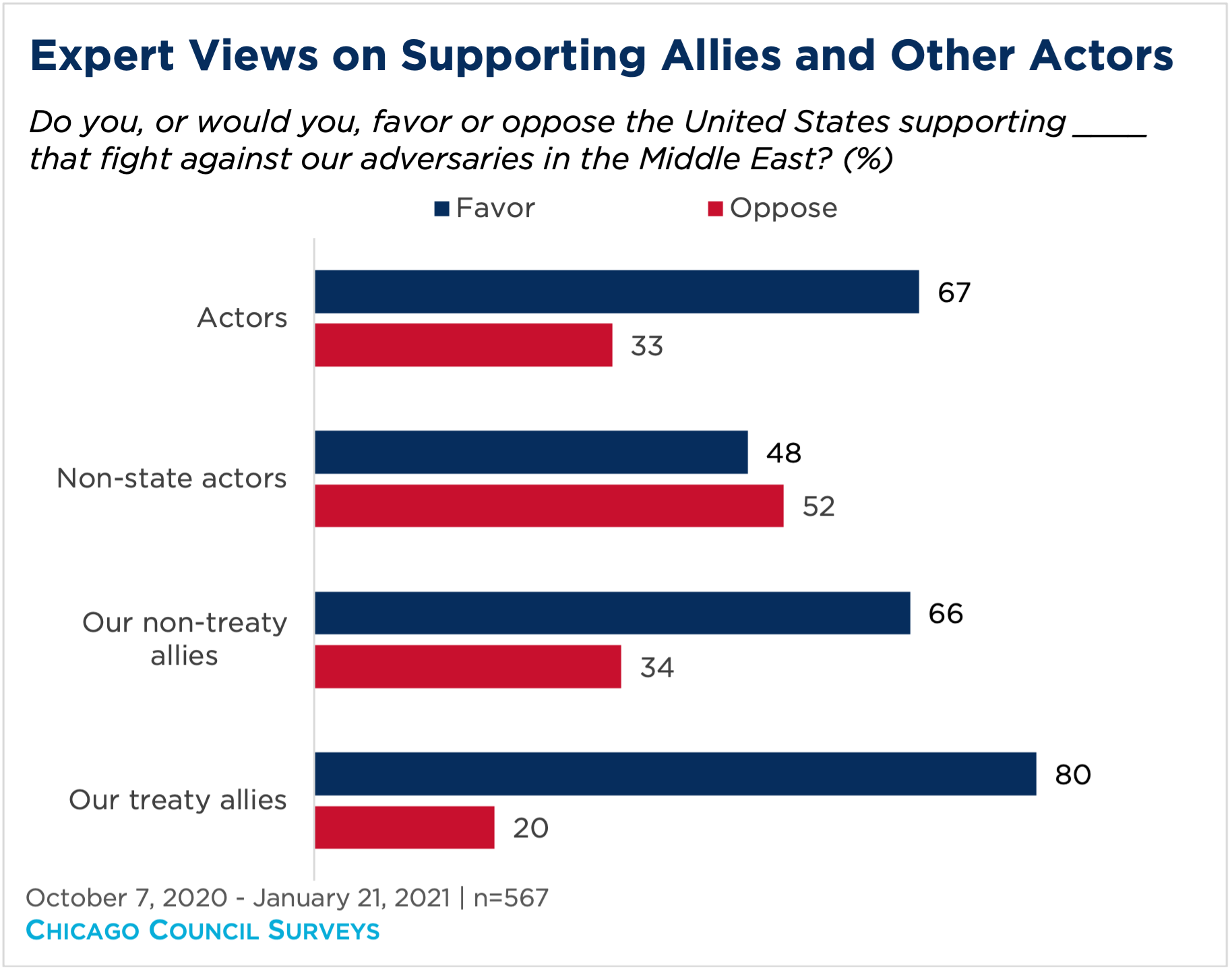

Policy experts more likely to support allies in conflicts

Respondents were asked whether they would favor or oppose international groups that fight against US adversaries in the Middle East. They received one of four scenarios with varying wording to capture the type of ally: treaty ally, nontreaty ally, nonstate actor, or, simply, actor. The results show that majorities support both treaty allies (80%) and non-treaty allies (66%), with a preference for the former. Most dramatically, a majority of respondents who received the “nonstate actor” scenario said they would oppose the United States supporting these actors, even if they fight against US adversaries in the region.

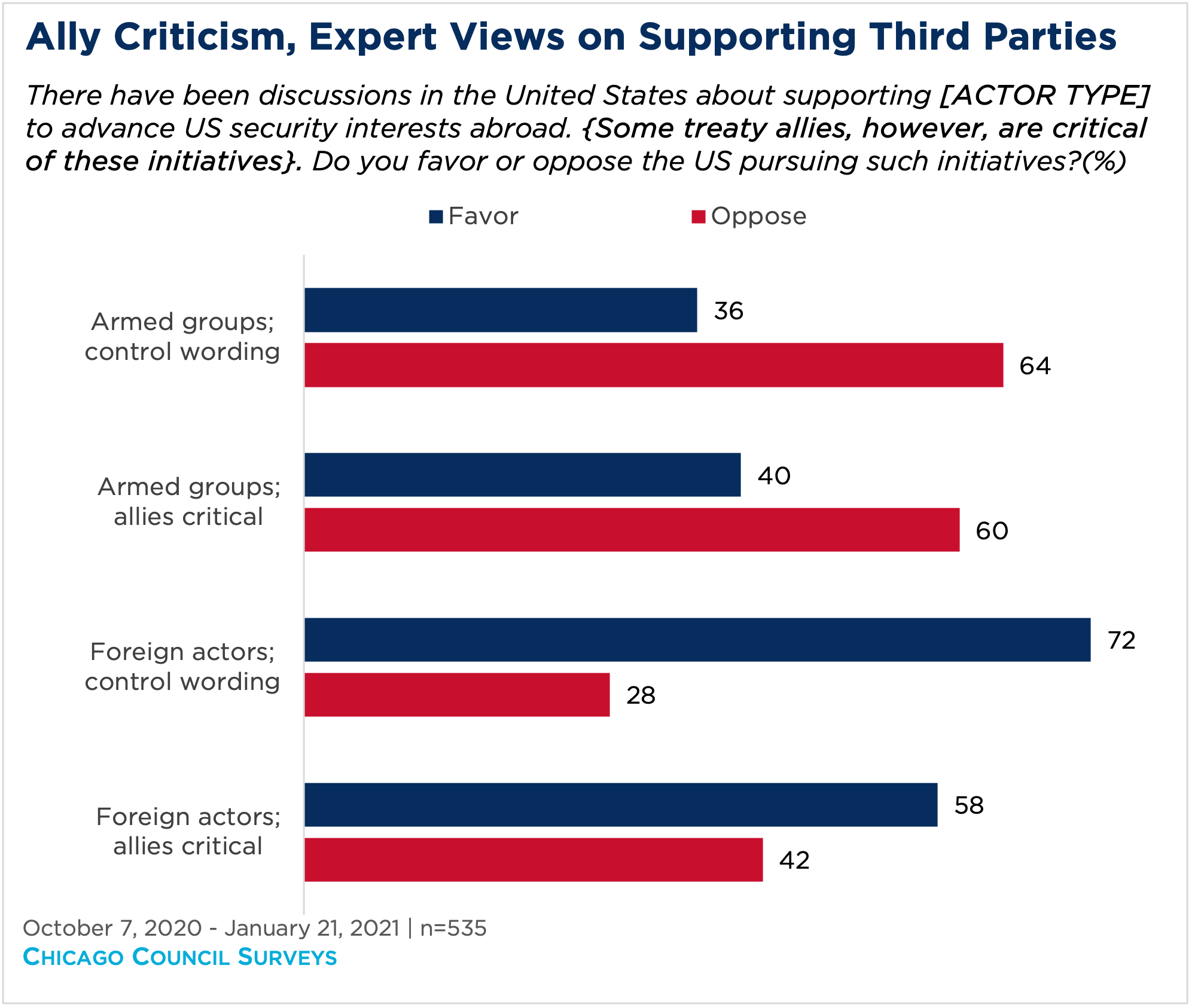

But experts don’t necessarily take into account allies’ criticisms

A second experiment examined whether foreign policy experts would prioritize America’s relationships with its treaty allies over other types of allies, by including this phrase for some respondents: “Some treaty allies, however, are critical of these initiatives.”

However, there were no statistical differences in each of the cases that included the wording about treaty allies being critical of the initiatives. In other words, the position of the treaty allies themselves did not matter for our respondents. The data seem to say that national security interests are the top priority for these elites, and they think treaty allies can be pushed aside to realize them. This, in fact, has been President Biden’s line on Afghanistan for years, and he has strenuously defended the pullout of US troops as being in US national interests.

A mixed bag for treaty allies

As we argue in the full survey brief, the results of the experiments are a mixed bag for US allies. While American policy experts do indeed value treaty allies more highly than other actors, that doesn’t necessarily give allies the influence they might expect (or desire) over US decision-making vis-à-vis other international actors.