Underground climate change is slowly sinking Chicago and cities across the globe

We know Venice is sinking. What about Chicago, which accounts for about 234 square miles of land?

Beneath Chicago’s iconic skyline lurks a sinking problem: underground climate change. Over time, its effects could jeopardize the durability of buildings and infrastructure across the city.

Also known as subsurface heat islands, heat emitted from underground structures, such as parking garages, basements, subway tunnels, and sewers, gradually deforms the surrounding earth. Existing structures aren’t designed to withstand those variations, so subtle shifts, tilts, and even cracks in infrastructure can occur.

This silent hazard is a slow but continual process, and it's affecting urban areas worldwide.

“You don’t need to live in Venice to live in a city that is sinking — even if the causes for such phenomena are completely different,” said Alessandro Rotta Loria, assistant professor of civil and environmental engineering at Northwestern University.

Chicago becomes a lab

Though the effects of underground climate change have been examined for years, researchers at Northwestern, led by Rotta Loria, were the first to study this phenomenon from a civil engineering perspective.

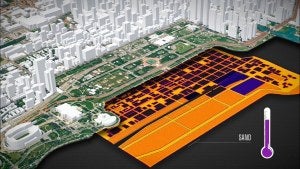

Using computer simulations and a wireless network of more than 150 temperature sensors above and below ground, for three years Rotta Loria’s team transformed Chicago's Loop — the most densely populated district in the U.S. after Manhattan — into a testing ground. They also installed sensors beneath Grant Park for comparison.

According to their findings, temperatures below Chicago are rising by about 0.25 degrees Fahrenheit (0.14 Celsius) each year. This has caused layers of soil to swell and expand upward in some locations by as much as 0.47 inches (12 millimeters), and contract and sink downward in other locations by as much as 0.31 inches (8 millimeters). They also found that the ground under the Loop was often 18 F (10 C) warmer than the ground beneath Grant Park, an unbuilt environment.

“Chicago clay can contract when heated, like many other fine-grained soils,” said Rotta Loria. “As a result of temperature increases underground, many foundations downtown are undergoing unwanted settlement, slowly but continuously.”

Play Video

Play Video

Not just a local phenomenon

Temperatures below various cities across the globe are warming at an average rate of 1.8 to 4.5 F (0.1 to 2.5 C) per decade.

Rotta Loria told ChicagoGlobal that underground climate change occurs in all urban areas worldwide, but some experience more severe effects than others. Intensity varies depending on the density, age, architectural characteristics, and layout of the built environment. It also varies by neighborhood, and even where you are within that neighborhood.

Small towns emit heat into the ground, but "it’s negligible compared to cities such as London, New York, Paris, Milan, Miami ... London is probably the city where subsurface urban heat islands are the most intense across the entire world,” said Rotta Loria.

Like Chicago, London is built on clay-heavy soil — something common near bodies of water, making the ground more susceptible to heat and deformation. And similar to many other European cities, London is dense and has several old buildings, which are particularly prone to subsurface heat diffusion. But it’s the Tube, London’s rapid transit system, that's the biggest contributor.

With no way to properly remove the heat emitted from trains that have run deep underground for more than a century, it has baked the clay surrounding the tunnels. Tunnels that were once 57 F (14 C) in the early 1900s now experience temperatures as high as 86 F (30 C).

London’s Bank Underground Tube station.

How could this affect local businesses?

Although Chicago’s buildings and infrastructure aren’t in immediate danger of collapsing, and therefore don’t pose any current threats to residents, over time soil deformation can affect their durability, appearance, and operational requirements. This may cause structures to tilt, underground railway tracks to buckle, and water to seep through cracked foundation and onto walls.

And those are important — and potentially costly — issues to local developers and insurance professionals. However, according to the Chicago Tribune, neither group is planning to make any changes to buildings or policies until more research on subsurface heat islands is conducted. It’s considered an emerging risk at this time, and coverage for damage “remains to be seen.”

“We’re looking at it more anecdotally than I would say we’re doing research studies on that specific thing,” said Steve Bowen, chief science officer at Gallagher Re, a global reinsurance broker, to ChicagoGlobal. He added that it’s probably something that needs to be top of mind more than people realize, “but there’s no widespread, imminent risk.”

What can be done?

Right now, it’s hard to see the effects of underground climate change, said Asal Bidarmaghz, a senior lecturer in geotechnical engineering at the University of New South Wales in Australia, in an interview with The New York Times. “But in the next 100 years, there is a problem. And if we just sit for the next 100 years and wait 100 years to solve it, then that would be a massive problem.”

The good news is that some scientists see this as an opportunity.

Interventions aimed at enhancing energy efficiency and reutilizing subsurface heat waste are, according to Rotta Loria, “two concrete and relatively straightforward mitigation strategies” that would help reduce the effect that underground climate change is having on urban areas, as well as harness renewable energy. It's also important to revise current urban planning strategies.

Installing thermal insulation in underground structures could minimize the amount of heat escaping into the ground. And using geothermal technology to absorb heat and reuse it to warm the very structures pumping it out could be an eco-friendly and sustainable alternative.

This story first appeared in the ChicagoGlobal newsletter, a joint project of Crain's Chicago Business and the Chicago Council on Global Affairs.