'Juggling glitter': How chambers of commerce in Chicago's commercial corridors are responding to the influx of migrants

In some of Chicago’s busiest commercial corridors, chambers of commerce and small businesses are coordinating with the city to plug gaps in Chicago’s response to the influx of migrants.

In some of Chicago’s busiest commercial corridors, chambers of commerce and small businesses are coordinating with the city to plug gaps in Chicago’s response to the influx of migrants.

The Andersonville Chamber of Commerce has a small staff, and organizing support for the city’s surge of migrants has pushed its staff past a “stereotypical nine to five of what most chambers do,” said David Oakes, the district manager at the Andersonville Chamber of Commerce.

Nearby, Lincoln Square Ravenswood Chamber of Commerce vice president Ian Tobin started receiving calls from businesses about recent migrant arrivals late in the summer.

“We really didn’t have members calling with any concerns or complaints,” Tobin said, but they did have members who started to organize events and collect donations.

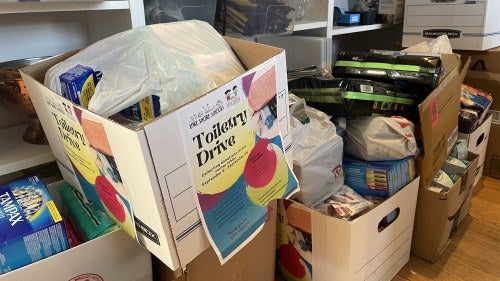

Currently, Oakes and his staff are working after hours to drop off the supplies they collect at their office: boxes of toiletries, bags of contact solution, and packs of pediatric toothbrushes and floss – all donated by local businesses and schools for migrants staying at police stations, churches, and the nearby Broadway Armory.

When asked if Oakes and the small chamber office could sustain this effort, he said, “we juggle glitter.” “We have always juggled glitter.”

Mobilizing businesses to support migrants

The Andersonville chamber reached out directly to businesses to ask them to donate supplies for migrants.

“This was kind of a no-brainer,” said Sarah Hollenbeck, co-owner of Clark Street’s feminist bookstore Women and Children First. The bookstore set up bins for toiletries and asked customers on social media to donate.

“We’re all sharing the same neighborhood: These are our neighbors,” she said. “It’s really blind to just pretend that this is not something that we’re all a part of and it’s not going to affect us on a larger scale long term.”

The chamber also said it reached out to vision and dental providers on Clark Street and asked them to donate supplies for migrants.

Michael Rabinowitz opened his pediatric dentistry practice in Andersonville in January. He lives close to the Addison Police Station, which is also sheltering migrants.

“I drive by it every day and see the tents. And I see the families, both children and adults,” he said.

When Oakes called Rabinowitz and asked for donations for about 200 migrant children, he ordered oral health care packs, including toothbrushes. Rabinowitz estimated it cost about $300 to $400 to provide supplies for the 200 children.

Rabinowitz donated dental supplies because he imagined the disruption to migrants’ day-to-day routines.

They have lost all semblance of normal. And I think brushing your teeth is one of the most normal things you can do.

Michael Rabinowitz

Pediatric dentist

Michael Rabinowitz

Pediatric dentist

Unless migrants – especially kids – have what they need to succeed, he added, “we were setting them up for failure before they even set a foot on the sidewalk.”

“And if [Oakes] asks me to do more, I would do more,” he said.

Helping migrants get permission to work

Finding jobs for the migrants is also a top priority. In September, the Biden administration granted Temporary Protected Status to an estimated 472,000 Venezuelans who have arrived in the U.S. since July 31. But getting migrants’ work permits approved is taking longer than the Andersonville and Lincoln Square Ravenswood chambers would like. Businesses can’t legally hire migrants until the paperwork is processed and approved.

“We’re asking for folks to speed it up,” said Oakes, who has been talking with Representative Jan Schakowsky (IL-09) about securing more work permits.

The chambers said they haven’t heard about many businesses successfully hiring new migrants. Both chambers pointed out that this could still be happening, but Oakes said that the federal government’s application approvals have been “extremely slow.”

Alderman Matt Martin’s 47th ward includes parts of Andersonville, Lincoln Square, and Ravenswood, and his office has collaborated with the chambers to support migrants who recently arrived. His office told ChicagoGlobal that the application includes several hurdles that might be too difficult for migrants to clear.

Applications for work permits cost more than $500 for most adults. Waiving this fee requires filling out an application in English and mailing it to Washington, D.C., according to Martin’s office.

The chambers organize job fairs and have worked with nonprofits that help with job placements for refugees, including migrants who have applied for asylum. But without work permits, it’s not clear how many recent arrivals could benefit from these services.

In the meantime, Oakes says, local block clubs are hiring migrants – usually for yard work in cash – to help support them.

In the long run, Tobin hopes that migrants can help relieve the labor shortage in Lincoln Square and Ravenswood.

“Writ large in Chicago, we’re seeing a labor shortage in hospitality, food production, health care, transportation. And these are people that could be employed to help fill the gap in those fields,” Tobin said.

Transitioning to winter

As the weather turns colder, Chicago is adapting its migrant response to prepare for winter. Plans include building temporary tent shelters for migrants. On October 19, Alderwoman Julia Ramirez and an aide were surrounded and allegedly assaulted by protesters upset with the city’s plan to open a tent camp for migrants in Brighton Park.

Neither the Andersonville chamber nor the Lincoln Square Ravenswood chamber said they have heard complaints about migrants from their members. So far, he’s only heard from businesses that want to “actively engage” and help provide material and financial support to migrants.

Hollenbeck says that shoppers in Andersonville “want to know that they are making a difference with their dollar.”

“I think it’s really easy to feel hopeless and disillusioned and helpless,” said Hollenbeck. But, she says, donating helps her fight back against those feelings.

“The least we can do,” Rabinowitz said, is “offer them compassion and support as a human.”

This story first appeared in the ChicagoGlobal newsletter, a joint project of Crain's Chicago Business and the Chicago Council on Global Affairs.