How does Asian food delivery app Fantuan compete with Uber Eats and Grub Hub in Chicago?

Fantuan, which specializes in Asian cuisine, started delivering in the city in 2020 and earlier this year bought out its Chicago-based rival.

Ten years ago, Yaofei Feng was living the dream for many Chinese international students in the U.S. Fresh out of grad school at Oregon State, he’d landed a prime tech job as a software engineer at Amazon’s Seattle headquarters.

But just 18 months in, Feng quit.

“It’s kind of irresponsible,” he told ChicagoGlobal with a laugh.

But he had access to a promising new venture alongside his friend Randy Wu. Feng and Wu had met playing video games online, and Wu had just started his own food delivery company in Vancouver — often couriering orders across town himself. Feng went to college in Xi’an, a Chinese city with a population of 13 million, and, like Wu, he knew that food delivery apps were exploding in China’s hyper-dense cities, especially among college students and young people. China’s food delivery market is three times larger than that of the United States, and Chinese companies like Meituan — which today has over half a billion users — had pioneered new business models and services that hadn’t yet been adopted by Uber, DoorDash, or Chicago-based GrubHub.

That left a gap in the market: Chinese international students and immigrants didn’t have a Meituan-like alternative in North America. Feng joined Wu as a co-founder of Fantuan, which means rice balls, and the two started to replicate China’s food delivery business models in Canada, focusing primarily on Asian cuisine and immigrant communities.

Ten years later, Fantuan has expanded from Vancouver to over 70 other cities in Canada, Australia, the U.K., and the U.S. The company started delivering in Chicago in 2020 and earlier this year bought out Chicago-based rival Chowbus, further expanding its operations in Chicago and Champaign. Now, after a period of rapid growth, Feng is trying to stabilize Fantuan’s business — but he worries how changing U.S.-China relations and immigration policy might impact his business in the long run.

Localizing China’s food delivery model

Fantuan reached profitability just two years after its founding, and Feng attributes that success to the company’s efforts to center the underserved diaspora market by localizing China’s food delivery model in North American cities.

China’s tech industry is dominated by “super-apps” that try to be users’ one-stop-shop for multiple services. Mega-popular WeChat, for example, is an indispensable messaging/payments/social app all in one.

Initially, Fantuan grew by reaching customers directly inWeChat. When they did ultimately set up their own app, they designed its interface and look to feel familiar for Meituan and WeChat users.

As the app grew its customer base, a networking effect built up, too. Vendors’ reviews from users are often in Chinese, which feels more accessible for many new arrivals, thus attracting more Chinese speakers.

Still, critical parts of China’s food delivery business model remained irreplaceable.

For one thing, China’s delivery giants rely on couriers with e-bikes and scooters. These work well in densely populated cities like Beijing or Shanghai that are often snarled with traffic. But they weren’t as viable in sprawling American cities like Chicago, where customers and restaurants are more spread out. Today, most of Fantuan’s delivery vehicles in Chicago are cars, said Feng.

Tips were also an issue. For much of Fantuan’s consumer base — newly arrived Asian international students and immigrants — “tip culture is totally different,” said Feng. At the same time, Feng added, tips “contribute significant income” for Fantuan’s couriers. That’s led to some tension between Fantuan’s consumers and couriers.

“People, once they arrive — they need to get used to [tipping]. But we do our best to help them to get used to it,” he added.

Together, tipping and urban sprawl both contribute to higher prices for food delivery services than in China. In the U.S., delivery is usually 30-40% more expensive than dining in, while in China it’s just 10% more expensive.

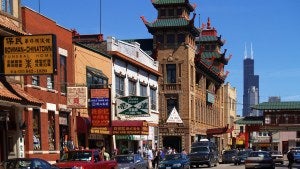

Restaurants in Chicago's Chinatown. (Photo: Marko Forsten)

The gate at the entrance of Chicago's Chinatown. (Photo: jpellgen)

Fantuan in Chicago

About 400 Chicago-area restaurants are on Fantuan’s mobile app, according to a company spokesperson. Many are small businesses specializing in Northeast Asian or Southeast Asian food, often based in Chinatown.

Feng says that narrow focus on Asian restaurants, especially mom-and-pops, is intentional — and something he wants to preserve.

“A lot of people ask, ‘What’s our differentiation compared with Uber Eats, DoorDash, or GrubHub?,” he said.

“If you open Fantuan’s app, we have so many different styles of Chinese cuisine,” he continued. “We have northern-style BBQ, Hong Kong-style dim sum, western-style noodles [and] lamb, hot pot, mala tang….It’s not like you open Uber Eats app and there’s only one tab called Chinese food.”

Still, Fantuan’s Chicago business is just about 20% as large as its self-described “tier 1” markets in San Francisco, Los Angeles, and New York. That’s in part because, compared to these coastal cities, Chicago’s Asian community is much smaller.

It’s also in part due to the success of Chowbus, a Chicago-based food delivery company that also focused on Asian cuisine and a similar consumer base. Feng says the competition with Chowbus in Chicago was intense because the latter had strong relationships with vendors. While Fantuan was winning the competition in other cities, Chowbus had stronger market penetration in the Windy City.

Fantuan’s expansion in other U.S. cities, however, helped power investor enthusiasm, and the company raised $40 million in series C funding in December 2023. One month later, Fantuan acquired Chowbus — and its customers.

On the vendor side, high-end restaurant Wagyu House said partnering with Fantuan has been a success. Wagyu House, located just west of the museum campus, has worked with Fantuan for several years, including at its West Coast locations, according to general manager Bin Lu. They also use UberEats, DoorDash, and Fantuan competitor Hungry Panda.

“Other to-go apps, they just set up a menu and that’s it. They don’t even care about anything: customer complaints, servers, delivery,” said Lu. But he said Fantuan has been more supportive when there are issues with drivers or to-go orders. His team meets monthly with Fantuan’s sales rep, and when Fantuan ran a promotion for Wagyu House in December, the restaurant received over 3,000 orders.

Lu notes that most customers ordering Wagyu House on Fantuan speak Chinese, but he would like to see Fantuan expand its customer base in the future.

Feng demoed what that pitch might look like in his interview with ChicagoGlobal. He thinks customers who like “authentic Chinese food” might be interested in using Fantuan to find more unique restaurants and dishes.

Still, Feng said that Fantuan’s primary goal in Chicago — and nationally — is to stabilize operations after a period of rapid growth. He also wants to see Fantuan increase its market penetration among Asian communities in the U.S., which still lags behind Canada.

“We worry about less people coming”

That stability is threatened not only by market conditions, but also by geopolitics.

After nearly a decade of growth, chilled U.S.-China relations and the COVID-19 pandemic led to a decrease in the number of Chinese international students studying in the U.S. While the trend has stabilized in the last two years, the total number of students in the 2022-2023 academic year was still 80,000 students below the pre-pandemic peak — a 22% decrease.

That threatens Fantuan’s consumer base, as does the pall in U.S.-China relations. Some heavy hitters from China’s tech sector have invested in Fantuan, including co-founders from Alibaba-owned ele.me and Meituan-owned Dianping (a Yelp-like app) and a VC firm founded by Eddie Wu, who recently became Alibaba’s CEO. Feng says investors from mainland China, who account for 10-20% of the company’s ownership, are sometimes concerned that the chilly relationship between the U.S. and China could affect Fantuan’s business.

To counter that, when Feng presents to investors, he’s quick to emphasize that Fantuan is a Canadian company, and that he and his co-founder both have Canadian status.

“We always say this is a Canadian company. We have some Chinese background or Chinese culture in the company — but anyway, it’s a Canadian [company].”

He also points out that Fantuan has no relationship with the Chinese government.

Governmental policies are ultimately “something we cannot control,” Feng admits, but they are still a concern. Future changes in immigration policy could limit the flow of new arrivals in both the U.S. and Canada, potentially posing a long-run risk to Fantuan’s business model.

“We worry about less people coming, since we serve that community,” said Feng. “We serve the newcomers.”

This story first appeared in the ChicagoGlobal newsletter, a joint project of Crain's Chicago Business and the Chicago Council on Global Affairs.