At APEC, Trump and Xi Seek a US-China Trade Truce

A short-term deal on soybeans, tariffs, and rare earths may ease tensions between the two economies, but competition over technology and supply chains runs far deeper.

US President Donald Trump and Chinese President Xi Jinping will meet later this week in South Korea on the sidelines of the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) Summit. With 21 member economies (Hong Kong has its own seat at the table), the APEC forum covers 3 billion people and roughly 60 percent of global GDP. On the table for Trump and Xi to consider at this year’s convening: a framework of a trade deal between the two countries—APEC’s largest economies.

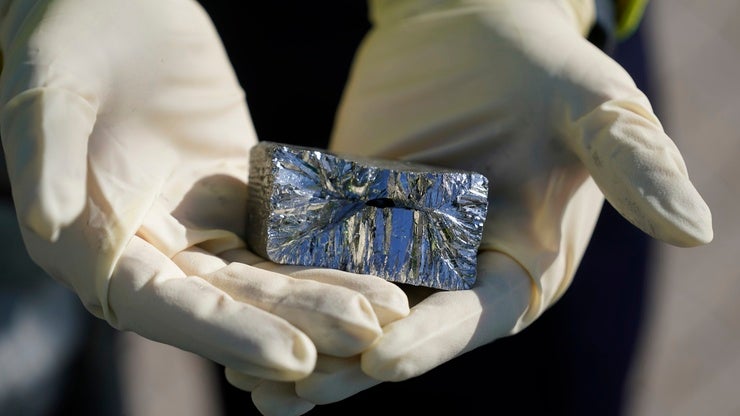

A key goal for the United States is pushing back on China’s export controls on rare-earth elements, which the US military depends on. Each F-35—the premier 5th-generation fighter jet in the US arsenal—requires roughly 50 pounds of samarium magnets to produce. China is currently the world’s sole supplier of samarium.

Soybeans are also on Trump’s mind going into negotiations. In retaliation for the Trump administration’s early tariffs on China over fentanyl, China completely cut the United States out of its soybean purchasing, turning to countries like Brazil and Argentina, and leaving American farmers in the lurch.

For its part, China seeks to avoid the huge tariff hike Trump has been threatening and push off or eliminate fees on Chinese ships that dock at US ports.

For people on both sides of the Pacific, a deal between Washington and Beijing would be received as good news. However, an agreement—should one come to pass—would likely serve as a pause in the economic conflict between the United States and China rather than a real turning point in the relationship.

Over the past decade, Beijing has increasingly focused on economic security as a core national priority. The recent Fourth Plenum of the Chinese Communist Party continued this theme, emphasizing the necessity for China to “seize the commanding heights of scientific and technical development.”

"An agreement—should one come to pass—would likely serve as a pause in the economic conflict between the United States and China rather than a real turning point in the relationship."

China’s drive for economic security will necessarily limit how exposed the country is willing to be to a potentially hostile power like the United States—a country that, according to most Chinese citizens, is not a friend to China.

Beijing isn’t the first to see economic networks as sources of both power and vulnerability. The United States has, for several decades, grown increasingly adept at using its central position in international networks of data and finance to impose its preferences on other countries. Dubbed ‘weaponized interdependence’ by scholars Henry Farrell and Abraham L. Newman, the concept has found an eager audience around the world. China’s recent rollout of rare earth export controls modeled on the US export control model is a clear signal that China, though it decries the long-arm jurisdiction approach of Washington, has decided to fight fire with fire.

In this vision of the world, the United States would likely need to construct an international system of secure supply chains, relying on allies and partners around the world to compete with China’s industrial might. This is, to put it mildly, not the approach the Trump administration has taken.

A trade deal would also not bring back the pre-trade war status quo. Unlike an exogenous event—a hurricane, an earthquake, a pandemic—the latest round of economic pain has been entirely man-made, and those responsible for it remain in positions of power.

"Unlike an exogenous event—a hurricane, an earthquake, a pandemic—the latest round of economic pain has been entirely man-made, and those responsible for it remain in positions of power."

The current congressional preference for ceding power to the president further increases uncertainty about future policymaking. With fewer people having real control over the economic levers of power, their peculiarities and preferences have an outsized impact on policy outcomes—a general problem of personalist governance. As a result, Chinese policymakers cannot simply assume that their DC-based counterparts won’t come back with a fresh round of tariffs next year, or the year after.

This isn’t to say that US-China relations can’t improve. A trade agreement that removes many of the recently added barriers to exchange between the two economies could pave the way for a smoother relationship between Washington and Beijing. Trump is said to be planning a visit to Beijing early next year, and a future Xi visit to the United States could be in the cards.

That said, trade is not the only sticking point between the United States and China. The status of Taiwan and US support for the island has long been a sore point for Beijing. US Secretary of State Marco Rubio has said that no concessions on Taiwan were on the table for this meeting. Yet the administration’s hold on arms sales to Taipei earlier this year, and Trump’s general disinterest in defending US partners and allies, has led to fear in the US policy expert community that Trump may be tempted to “sell out” Taiwan in exchange for trade concessions from Beijing.

A true Trump-Xi rapprochement would likely raise a different set of concerns in other capitals around the region, as many US allies and partners in Asia fear the idea of a “G-2,” in which the United States and China make bilateral decisions on multinational issues. But given how far apart the two sides are on a whole host of issues, those problems seem very far away today.

In the immediate term, the most likely scenario is that Trump and Xi reach an agreement that rolls back many, but not all, of the most recently imposed trade restrictions. Tariff levels are likely to remain significantly higher than they were a year ago—a lesser drag on economic growth than at present, but worse than the status quo ante. China’s pledge to purchase soybeans will give US farmers a lifeline, but as was true in the “Phase One” deal announced early in 2020, it is unlikely that China will hit purchasing targets. Other issues—like Chinese rare earth restrictions and US high-end semiconductor sales—are unlikely to be resolved anytime soon. Those will be problems for another summit in another year. In the meantime, both sides will seek to develop alternatives: the US will continue to look for other sources of rare earths, while China will continue its quest for technological sovereignty.

A deal will also give Trump and Xi a needed break from the trade war. They both have other priorities at home. For Xi, those priorities include continuing the ‘political rectification’ of the People’s Liberation Army and doubling down on the pursuit of “high quality development.” For Trump, his agenda upon his return will include ending the nearly month-long government shutdown, potentially expanding US military operations against Venezuela, and continuing his administration’s domestic immigration crackdown. And, of course, building a new White House ballroom.

Related Content