Trump's Approach to Latin America Is Not Such an Outlier

The Trump administration's recent posture toward Venezuela reflects a long-standing focus of US foreign policy: control of the Western Hemisphere.

This analysis was first published in World Politics Review.

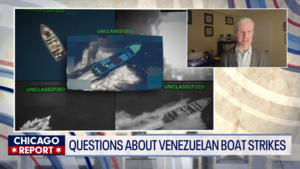

In recent weeks, US President Donald Trump has raised the pressure he has been putting on Venezuela since earlier this year. In addition to the now months-long campaign of bombings targeting alleged drug-trafficking boats in the Caribbean—a campaign whose legal underpinnings are rejected by most experts and under growing congressional scrutiny—the administration has amassed naval forces in the region, declared the airspace over Venezuela closed and made threats to conduct ground operations.

One might look at these actions and see them as incongruous with Trump’s much-touted “America First” foreign policy. Specifically, it seems that he is on the verge of pursuing the very kind of “regime change” operation that he criticized previous administrations for undertaking. One could also point out that Trump’s criticism of Venezuelan President Nicolas Maduro as an autocratic dictator seems inconsistent with his seeming admiration for other autocrats, such as Russia’s Vladimir Putin and China’s Xi Jinping.

One would not be wrong in pointing to these apparent contradictions. But another way to understand Trump’s actions is that his America First approach is perfectly compatible—and even consistent—with a long-standing essential trait of US foreign policy: control of the Western Hemisphere.

In the years after it gained independence from Britain, the newly founded United States was understandably focused on its immediate neighborhood. The early American Republic was in a precarious position, facing the possibility of war in the Western Hemisphere with the major European powers, particularly Britain and Spain.

As the US gradually gained its geopolitical footing and established itself as a regional power, it began to focus not on surviving external threats, but on preventing them from arising. This meant curtailing the influence of foreign powers in the Americas and the Caribbean. In 1823, following the wave of decolonization throughout the region in the early part of the 19th century, then-President James Monroe issued the famous doctrine that would go on to bear his name. Fearing that the European powers would seek to reassert colonial control in the region, the Monroe Doctrine held that Washington would view coercive acts by European nations in its hemisphere as an act of aggression against the United States. In short, according to the United States, only the United States could exercise influence in the region.

But the US wasn’t just seeking to dominate its “neighborhood,” or at least prevent the European powers from doing so. Influential elements within the United States, particularly Southern elites, hoped to actually annex and conquer parts of the region. These efforts were most visibly illustrated by the Mexican-American War from 1846-1848, which fed desires to eventually expand US territorial annexation further southward, a key contributor to the debates that eventually led to the Civil War.

As the 19th century came to a close, US policy toward the hemisphere underwent perhaps its most notable transformation. Following its defeat of Spain in the Spanish-American War, the United States was now fully recognized not only as the hemispheric power, but as a global great power. Due to its victory, the U.S. militarily occupied Cuba and took control of Puerto Rico. It would go on to gain control of the Canal Zone in Panama and what are now the US Virgin Islands from the Dutch. To cap things off, in his 1904 “Corollary” to the Monroe Doctrine, then-President Theodore Roosevelt declared that the U.S. would directly intervene in Latin American countries, ostensibly for the purpose of preventing Europeans from doing so.

For many, this is a largely familiar story, which is why Trump’s actions have been characterized as an attempt to reinstate the Monroe Doctrine, with some going so far as to label the administration’s approach to the region as the “Donroe Doctrine”. Even Trump’s White House made this connection, making a point of commemorating the anniversary of the doctrine’s initial declaration this week and declaring a “Trump Corollary” to the Monroe Doctrine, which it referred to in its just released National Security Strategy.

The 1980s and then the end of the Cold War did not change the underlying dynamics driving US regional policy, even if they changed the superficial aspects used to justify it.

Viewing Trump through this lens makes sense, given his predilection to behave like a 19th-century president. As I have argued, Trump is a throwback to a time when the US was more focused on its own hemisphere, rather than the wider world. With the World Wars of the early to mid-20th century, the United States became focused on building the global hegemonic order Trump so often derides, rather than satisfying itself with regional dominance.

But as much as this view may explain Trump’s motivations, it distorts the arc of US foreign policy. Ever since its founding, the US has engaged globally, though mostly as a commercial power. But more pertinent to the point of this column, the United States never stopped being regionally focused, nor did it ever really subordinate its own national interests to that of the global order. Indeed, its foreign policy during the World Wars and the Cold War was very much an “America First” approach, particularly in the Americas. In other words, the Monroe Doctrine never needed to be reinstated because the defense of the Western Hemisphere remained a core element of US policy.

During World War I, the United States remained on the sidelines until it was no longer evident that its “big beautiful oceans”—as Trump called its natural protective borders to the East and West—could keep the war at bay. From the discovery of Germany’s “Zimmermann telegram,” in which Berlin secretly proposed an alliance with Mexico, to the fact that US merchant ships could not carry out their commerce without being targeted by German submarines, then-President Woodrow Wilson’s administration had no shortage of self-serving reasons to enter the war in Europe. Wilson asserted that America was doing so “to make the world safe for democracy,” but it was really to make the world safe for the United States to return to business as usual.

When World War II broke out, it again made it clear to US policymakers that solely focusing on protecting US hegemony in the Western Hemisphere was not an option. In addition to the fear that Nazi Germany, if not stopped, could eventually intervene in the hemisphere, US planners recognized that securing the region required securing a larger “Grand Area,” with the Western Hemisphere at its core.

This is why the first mutual defense alliance that the United States formed after World War II was the Rio Pact, which eventually became the foundation on which the Organization of American States was built. Indeed, the Rio Pact’s mutual defense clause was actually the model for NATO’s Article 5, though it never received the same amount of attention.

Throughout the Cold War, the Rio Pact served as a platform for the United States to counter and prevent the spread of communism in the region. The failure to do so in Cuba, combined with the Cuban Missile Crisis, only heightened the urgency of the perceived threat to America’s regional influence during the early decades of the Cold War.

The 1980s and then the end of the Cold War did not change the underlying dynamics driving US regional policy, even if they changed the superficial aspects used to justify it. The need to stop communism during the Cold War became the so-called War on Drugs’ effort to stop the flow of cocaine and other illicit narcotics into the United States. This was perhaps best captured symbolically by the US military intervention in Panama in December 1989—just a month after the fall of the Berlin Wall—the purpose of which was to arrest the country’s then-leader, Manuel Noriega, for his alleged participation in drug trafficking. The quick success of that mission may well be what the Trump administration hopes to duplicate in Venezuela. By the end of the 1990s, the United States had launched Plan Colombia to provide military assistance to the government in Bogota to fight rebel groups that were also engaged in drug trafficking.

The United States also remained highly engaged economically in the region in this period, whether through the creation of the North American Free Trade Agreement with Canada and Mexico or a series of sovereign debt bailouts in the 1980s, 1990s and even the early 2000s. The Trump administration’s own pledge to provide a financial backstop to Argentina in recent months clearly follows in that tradition.

It was only during the first quarter of the 21st century that the United States started ignoring Latin America, perhaps as a consequence of the 9/11 terrorist attacks, which were a direct attack on the US homeland, but one that originated from far outside the region. In that sense, the Trump administration’s hemispheric focus is a departure from that of his immediate predecessors. But in the longer arc of US foreign policy, Trump’s use of militant coercion and economic influence represents more continuity than change.

Related Content

Global Politics

Global Politics

What’s really driving Washington’s new hard line on Caracas—is this a bold policy shift?

US Foreign Policy

US Foreign Policy

Nonresident Senior Fellow Paul Poast unpacks the recent US strikes on Venezuelan boats and the risks involved with a potential US push for regime change.