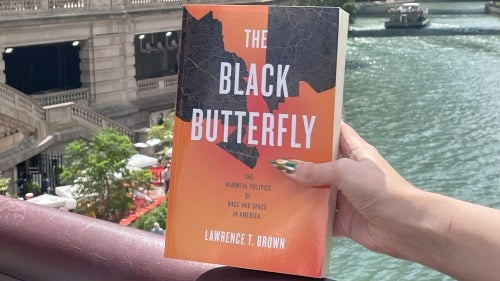

Reversing Urban Apartheid: Lessons from Lawrence T. Brown's The Black Butterfly

Pattis Family Foundation Global Cities Book Award finalist, The Black Butterfly, uses the city of Baltimore to examine the policies, practices, and historical trauma that created hyper-segregation in today’s cities.

In August 2023, the Council announced the six-title shortlist for the inaugural 2023 Pattis Family Foundation Global Cities Book Award, which celebrates books that deepen our understanding of the role cities play in addressing critical global challenges. Over the coming weeks, we’ll be sharing interviews with the shortlisted authors discussing their books and the pressing issues facing cities today.

Throughout The Black Butterfly: The Harmful Politics of Race and Space in America, Lawrence T. Brown uses the city of Baltimore—where the majority-black population fans out among prime city real estate like butterfly wings—to examine the policies, practices, and ongoing historical trauma that created hyper-segregation in today’s cities.

Brown is an equity scientist, urban Afrofuturist, and the director of the Black Butterfly Academy, a racial equity education and consulting firm, and a research scientist in the new Center for Urban Health Equity at Morgan State University. He recently joined us for a conversation on the influences of his book. The authors responses have been lightly edited.

Q: Cities are not just places but are becoming actors in shaping local and international policy. What lessons do you hope other cities take away from your book?

A: I hope city officials, agencies, residents, and organizers glean from The Black Butterfly that urban apartheid hurts lives worldwide. Globally, urban apartheid can take the form of racial segregation and forced uprootings (such as in the United States and Brazil), caste systems (India and Nepal), or formal apartheid (South Africa and Namibia).

I also discuss community-wide historical trauma which consists of racial segregation and forced uprootings. Without stopping and healing ongoing historical trauma, eventually anger and frustration will boil over into urban uprisings. Hence, cities should reckon with how they have developed and begin ameliorating the harm that they have often inflicted.

Q: What is the greatest challenge facing cities today and how do cities move forward?

A: The greatest challenge facing cities today is making democracy real in redlined neighborhoods. You don’t have a democracy when entire neighborhoods are disinvested and ostracized by policies, practices, systems, and budgets.

In the United States and beyond, cities must acknowledge how they partnered with the federal government to enforce redlining and uproot entire communities. I outline the five steps of a racial equity process that’s crucial for moving forward:

- Deep reflection

- Identification

- Democratic participation

- Collective ownership

- Reparative budgets

Cities can move forward by engaging in all five steps iteratively and authentically.

Q: Which book(s) influenced you the most in crafting yours?

A: Eve Ewing’s Ghost in the Schoolyard was my top inspiration from a technical standpoint. She offered definitions for key terms at the front of the book. She made the politics and impacts of Chicago’s mass school closures readable and lyrical. I worked to incorporate these attributes into The Black Butterfly.

From a content standpoint, Wangari Maathai’s The Challenge for Africa was deeply influential. I loved how straightforward and solutions-driven Maathai was in her writing. Maathai found a way to address so many issues in her book and I wanted my book to do the same.

Q: What area of study did you intend your book to contribute to, and why did you choose that topic to write on?

A: I am a public health scholar, so I intended to push the field of public health forward. Public health researchers usually write obliquely about social determinants of health, neighborhood indicators, and health outcomes.

These are very broad terms that have their utility, but they gloss over the granularity needed to understand what happened and how we can move forward. I wanted to center the story of Black neighborhoods in Category 5 hyper-segregated cities (using hurricanes as an analogy). I aimed to explain the policies and practices that damaged Black neighborhoods and placed them at the bottom of historically deficient data points and stigmatizing statistics. Data and statistics don’t tell the whole story.

Beyond this, however, I wanted to discuss what cities could do to reverse course. So, I also spent the last third of the book detailing the radical solutions cities should undertake to address radical problems.

Q: What are you trying to achieve with your book?

A: There were several audiences I had in mind: city officials, nonprofit institutions, public health professionals, and racial justice organizers. For city officials, I wanted to highlight how local policies undergird urban apartheid and provide solutions that could help reverse the damage. For nonprofits, I sought to call attention to the role they play in influencing city government and provoke them to rethink their policy agendas.

For public health professionals, I wanted to encourage the field to think about what is needed to help a community heal from ongoing historical trauma. For racial justice organizers, I wanted to inspire local level activists to consider that making Black Lives Matter means ensuring Black neighborhoods matter, especially in Category 5 hyper-segregated cities—such as Chicago, Baltimore, Detroit, Flint, St. Louis, Birmingham, Cleveland, and Milwaukee.