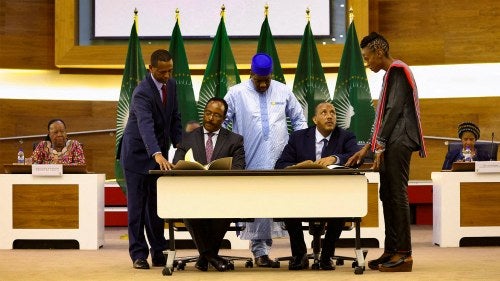

With Peace Deal, Ethiopia and Tigray Rebels Acknowledge War's Toll

A ceasefire between Ethiopian government forces and Tigrayan rebels brings optimism after years of fighting.

The Horn of Africa is in urgent need of some good news, and today there is just a sliver of it.

The on-off ceasefire between the Ethiopian government and Tigrayan rebels appears to be on again, creating a desperately-needed window for the international community to do more to respond to one of the world’s worst humanitarian crises.

The African Union called it a ‘new dawn’ for Ethiopia, and said it included an immediate cessation of hostilities as well as a detailed program of disarmament.

The war in Tigray, on Ethiopia’s northern border with Eritrea, has not received widespread international attention, but it has been unspeakably brutal.

The bare statistics struggle to convey the scale of suffering. The United Nations says tens of thousands of people have been killed in the last two years, but there are well-researched estimates that it could be hundreds of thousands, and there have been multiple reports of atrocities. Millions of people have been forced from their homes, and are now at risk of famine.

That is why it is so important that today’s deal also includes a commitment to ‘unfettered access for humanitarian supplies.’ But the first question is whether the ceasefire will last? A previous truce, agreed in March after 16 months of fighting, broke down in August, to deadly effect.

This time, the basis for the ceasefire appears to be more secure. The two sides have been negotiating directly under African Union mediation, with the active involvement of the UN.

The Tigrayan rebel leadership has acknowledged that it has had to make concessions in order to build trust. But implementing what has been agreed on paper will be an enormous challenge.

The Ethiopian government has been accused of starving the civilian population in order to try to secure military victory, so confidence-building measures will need to be carefully developed and continuously monitored. A small spark could easily restart the fire.

The UN Secretary General António Guterres recently called the conflict catastrophic. And if an end to the fighting really has been agreed, the biggest need will be to get humanitarian aid into Tigray as soon as possible, to feed the hungry, and to begin to create conditions which will allow people to return to their homes.

The war has also caused a wider economic crisis in Ethiopia, the second most populous country in Africa. It has lost access to billions of dollars in economic support from its donors, inflation has soared, and hopes that it could become a regional engine for growth have stalled.

So, both federal government and rebel leaders should have an interest in peace. The complexity of the conflict in Tigray is such that it will not be solved at the stroke of a pen. But the need for humanitarian assistance is so great that both sides may have been persuaded that now is the time to try to start building towards a more lasting solution.

Related Content

Global Politics

Global Politics