The Importance of Race in Attitudes Toward Trade and Globalization

Ethnic and racial minorities show greater support for globalization. These results indicate that trade is as much of a psychological and social issue as it is an economic issue.

Trade

Minorities in the United States express systematically more positive attitudes toward international trade than whites. This finding is puzzling in part because minorities are more economically vulnerable than Whites. They are more likely to experience unemployment, and their position in the national income and education distribution makes them an unlikely source of trade support. Nonetheless, we find systematically greater support for globalization among Americans who are ethnic and racial minorities. Because this pattern had not been previously noted, we used Chicago Council surveys to explore whether this was a recent phenomenon.

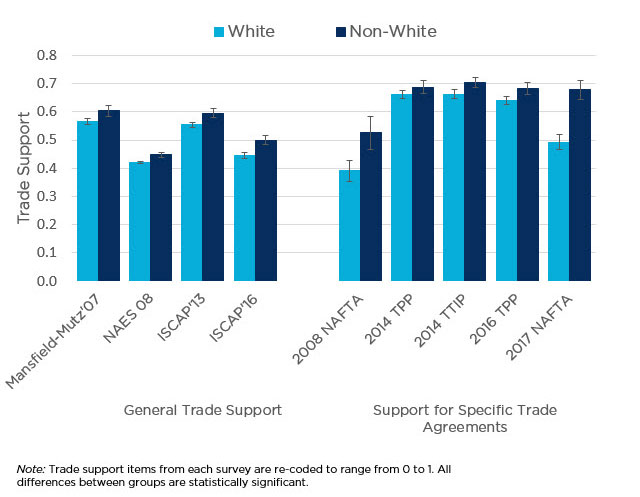

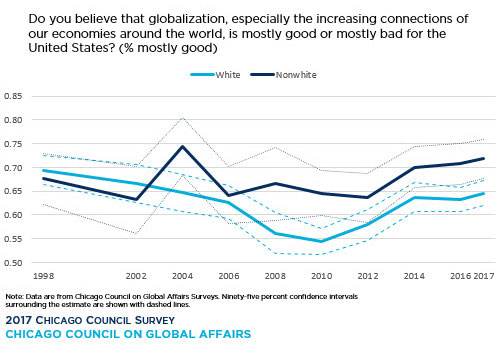

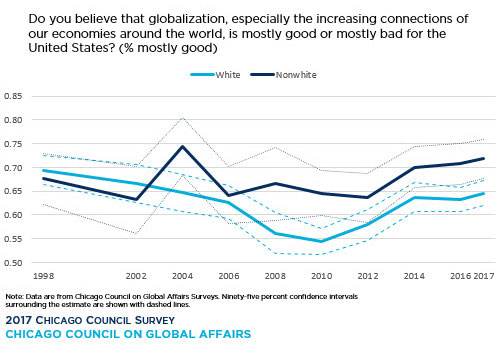

Drawing on CCGA surveys over a span of more than a decade, Figure 1 illustrates that from 2004 through 2017, minorities have been consistently more positive about trade than whites. Likewise, trade’s effects on jobs, a central focus of voter concern when it comes to the impact of trade, is more positively perceived among minorities. As shown in Figure 2, another question asking whether globalization is good or bad for the country demonstrates a similar pattern: minorities are consistently more likely to say that globalization is good for America.

Figure 1. Support for Trade Among Whites and Non-Whites

Figure 2: Trends over Time in Believing Globalization is Mostly Good by White/Minority Race

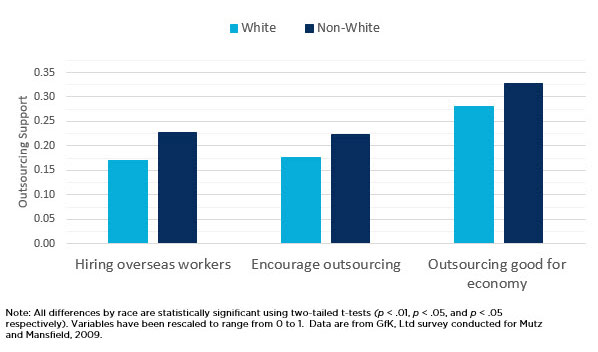

Drawing on other surveys, we found that minority support for globalization is not limited strictly to trade. Minorities are also substantially more supportive of offshore outsourcing than whites. Whether one considers strictly CCGA surveys or those from other sources, minorities are consistently more supportive of globalization whether it is in the form of NAFTA, TTIP or the TPP.

Figure 3: Positive Attitudes toward Outsourcing by White/Minority Race

How do we explain minority enthusiasm for globalization? It clearly predates the recent Republican turn toward protectionism. We used decomposition analysis (a technique borrowed from labor economics) to identify characteristics that might help account for these groups’ differing trade attitudes. Surprisingly, many of the likely suspects either had no bearing on trade attitudes (personal unemployment, average occupational wage, willingness to relocate for a job, being in an export versus import-oriented line of work, income, exposure to an economics course), or these characteristics did not differ among whites and minorities in a direction that would explain minorities’ greater trade support (market conservatism, education, economic knowledge, median income in the residential area).

Instead, minority enthusiasm for globalization reflects both demographics and social attitudes. First, white Americans are much older on average than minorities. The median age of American non-whites is 31 years, whereas the median age of whites is 43 (Gao 2016). Younger people are generally more supportive of international trade, so this helps to account for the white-minority difference. In addition, minorities are less likely to live in areas of the country with a heavy manufacturing base. Minorities are concentrated in urban areas, where there is less manufacturing. So even though people’s own industry of employment does not predict their trade attitudes, the kind of employment that is prevalent in the area where they live has a predictable impact.

Two underlying social attitudes also help explain differential levels of support. First, racial prejudice and ethnocentrism are known to predict trade opposition (Mansfield & Mutz 2009; Sabet 2013; Mutz & Kim 2017). Aversion to difference is highly generalizable, whether it is products or people crossing borders. Minorities are generally more accepting of majority group members than majority group members are of minorities. In this sense, ethnocentrism has been described as a “one way street,” in which dominant groups demonstrate stronger ingroup bias and outgroup prejudice (Tajfel 1982). For example, 62 percent of white Americans report that they would accept a Black person marrying into their family and over 70 percent would do so if the person is Asian or Hispanic. However, 83 percent of Blacks would accept a white, an Asian, or a Hispanic marrying into their family (Davenport 2017). Residential preferences reveal a similar pattern. whites’ willingness to move into a neighborhood is negatively related to the density of Blacks living there, but Blacks prefer integrated neighborhoods that incorporate ingroup as well as outgroup members (Farley, Fielding, & Krysan 1997).

Beyond differences in interracial attitudes, whites also express higher levels of nationalism than minorities in both the US and elsewhere (Theiss-Morse 2009; Cebotari 2015; Carter & Pérez 2015). Whites are more likely to view America as superior to other countries, and those who believe Americans are superior tend to believe the country would be better off going it alone economically. A nation’s dominant group often feels more ownership and a greater sense of belonging to the nation than lower-status groups (Sidanius et al. 1997). This variation in levels of national attachment also helps to explain minorities’ higher level of support for international trade.

Thus far we have combined all minorities into a single group due to the need for large-enough sample sizes to provide accurate statistical estimates. But using one unusually large representative probability survey allows us to break down our estimates of trade support into whites, Blacks, Hispanics and those of mixed or other races. As shown in Figure 4, all minority groups have higher levels of support for trade than whites, but Hispanics show the greatest enthusiasm. We can only speculate at this point as to the reasons, but it may stem from concerns about Latino workers beyond American borders.

Figure 4: Levels of Trade Support by Specific Racial Groups, 2008

These results have several noteworthy implications. First, they reinforce the findings of previous research that non-material factors heavily influence trade attitudes. The economic attributes of non-whites—most notably, the fact that they tend to be lower skilled, earn less, experience greater unemployment, and have less economic education than whites—provide ample reason to expect them to be especially hostile to trade and yet they are not. That they are particularly pro-trade stems from demographic characteristics (that is, relative age), national identity, and prejudice. Minorities are also less likely to live in areas dependent on manufacturing, a sector of the U.S. economy that has been hard-hit by trade. These results indicate that, for the mass public, trade is at least as much of a psychological and social issue as it is an economic issue.

In recent years when opposition to globalization has increased in the U.S., concerns have been raised that this trend could lead the government officials to raise trade barriers and scuttle trade agreements. These are important concerns, but to the extent that mass attitudes influence trade policy, there is reason for optimism. In less than three decades, the U.S. is expected to become a “minority majority” country. The rapidly rising non-white proportion of the population is likely to increase mass support for globalization.

A third implication is potentially more problematic. In the U.S., negative views of trade stem from the job loss it creates for workers in a shifting economy. Trade advocates often assume that if only the safety net in the U.S. were stronger, and more akin to that of some other countries, job displacement would be viewed less negatively and trade would receive more widespread support. However, the same people most likely to oppose trade are even more opposed to strengthening the safety net to help dislocated workers. This puts policymakers who may wish to alleviate public concerns about the negative consequences of trade in a bind. If White Americans view trade adjustment assistance as yet another government handout that they oppose, it will do little to increase their support for international trade.

For more details on these analyses, see The Impact of In-group Favoritism on Trade Preferences.