Emergent Tokyo: Almazán, McReynolds, and Saito on Organic Urban Growth

Global Cities Book Award Finalist "Emergent Tokyo" examines how the city balances massive growth and local communal life and can be a model for other cities.

In August 2023, the Council announced the six-title shortlist for the inaugural 2023 Pattis Family Foundation Global Cities Book Award, which celebrates books that deepen our understanding of the role cities play in addressing critical global challenges. Over the coming weeks, we’ll be sharing interviews with the shortlisted authors discussing their books and the pressing issues facing cities today.

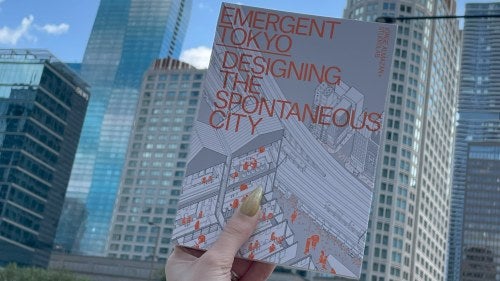

What lessons does the world’s largest metropolis hold for other global cities? In Emergent Tokyo: Designing the Spontaneous City, authors Jorge Almazán, Joe McReynolds, Naoki Saito, and Studiolab examine how Tokyo balances massive growth and local communal life and can be a model for other cities to emulate.

Almazán is a Spanish architect based in Tokyo, whose office is committed to environmentally responsible and socially inclusive projects. McReynolds is an urban studies scholar affiliated with Keio University, where he studies Tokyo’s approach to urban development; and Saito is an architect and assistant professor at Keio University, where he studies how urban space is formed by the interaction of human activity and infrastructure in Tokyo. They recently joined us for a conversation on the influences of their book. The author’s responses have been lightly edited.

Question: Cities are not just places but becoming actors in shaping local and international policy. What lessons do you hope other cities take away from your book?

Answer: Tokyo is both the world's largest city and one of its most livable, and our book offers a blueprint for how cities around the world can learn from Tokyo's strengths to develop dynamic and thriving communities. Tokyo's neighborhoods show that if we design our cityscapes to give citizens the legal and practical freedom to shape their communities from the ground up, this “emergent” urbanism produces a more livable city than either top-down master planning or a corporate-dominated laissez-faire approach.

Q: What is the greatest challenge facing cities today and how do cities move forward?

A: Cities worldwide are facing skyrocketing rents, growing wealth disparities and community displacement, social atomization, and the homogenization of urban space. Tokyo has notably been spared the steep rent increases of other urban capitals, due largely to its commitment to building much more new housing than almost any comparable global city. But beyond that obvious lesson, Tokyo demonstrates how a light touch to urban planning helps the cityscape evolve organically to address these ills via citizens’ bottom-up initiatives.

In particular, flexible "micro-spaces"—that is, smaller low-cost spaces which can fluidly shift between various residential and commercial uses with minimal friction—can help cities weather these negative trends. Micro-spaces allow neighborhoods to welcome new demographics without displacing their legacy residents, and make it much easier to run an independent, creative, or “mom-and-pop” business.

Q: Which book(s) influenced you the most in crafting yours?

A: In Emergent Tokyo, we dedicate an entire chapter to acknowledging and visually mapping more than one hundred works that have laid the intellectual foundation for both our book and the broader field of Tokyo studies. We draw particular inspiration from Jane Jacobs’ The Death and Life of Great American Cities and Christopher Alexander’s A Pattern Language.

Beyond these classics, Atelier Bow-Wow’s Made in Tokyo showed the world that the idiosyncratic architecture of Tokyo's cityscape was worthy of being celebrated, and Hidenobu Jinnai’s Tokyo: A Spatial Anthropology helped us to understand the surprising historical continuity between Tokyo's Edo-era past and its megacity present. Italo Calvino's Invisible Cities was also a subtle influence on our exploration of Tokyo's many different faces—a work of experimental fiction that explores the unique sensations and emotions that different cityscapes can evoke.

Q: What area of study did you intend your book to contribute to, and why did you choose that topic to write on?

A: We love Tokyo, but we did not write this book purely as an ode to our favorite city. We chose to write about Tokyo because we believe its unique strengths as a city do not have to be unique any longer; we believe that Tokyo offers a positive model of urbanism that the world can learn from.

Our book is intentionally aimed at not only practitioners—architects, urban planners, urbanist academics—but also ordinary people with an enthusiasm for cities who want to better understand the largest city on the planet. We are fortunate to live in a time when public interest in urbanism is at an all-time high, though much of that interest is driven by the increasingly fragile state of our cities at home. In the end, there is something for everyone to learn from Tokyo.

Q: What are you trying to achieve with your book?

A: Emergent Tokyo is in one sense specifically about Tokyo, but in another sense, it offers a broader argument about what a city can be. We want to not only demystify Tokyo for an English-speaking audience, but also to bring Tokyo’s key lessons for urban design to the world. Our book illustrates how urban spaces can adapt and evolve while preserving key values like social inclusivity and community, including fifteen detailed case studies of neighborhoods that have put these ideas into practice. Our greatest hope is to contribute, however modestly, to bringing Tokyo-style intimacy, adaptability, and spontaneity to cities around the world.