COVID-19 Silver Lining? New Opportunity for Midwest's Smaller Communities

Several forces propelled by the COVID-19 pandemic may intersect to spin new life into more of the Midwest's still-struggling factory towns, second-tier cities, and rural hinterlands.

COVID-19 and the Midwest

The need and desire to "distance" socially and a new pandemic-induced facility in doing so through distant work and learning, appears to be an early outcome. Another pandemic product, as students and workers were forced on-line, is a new understanding that already economically marginalized populations who lack internet access, in big cities as well as smaller towns and rural hinterlands, are further disadvantaged. There is growing momentum to make a post-pandemic priority, expansion of high speed internet access to more people and places. Finally, there is speculation that seemingly safer, more isolated, and less densely populated smaller communities will become an attractive location of choice for people and businesses who can afford to make their own work and life location decisions.

A broad expansion of high speed internet access could be a boon for many Midwest communities as people reconsider whether the "hothouse" cities of the coasts are where they want to live in a post-coronavirus world.

The Midwest is home to communities that thrived in the old agricultural and industrial economy. Many communities do still struggle to replace economic anchors of mills and manufacturing facilities. But the Midwest is no economic monolith of struggling factory towns and rural hinterlands—even if the national obsession with the region breathed new life into this "Rust Belt" image after the region’s pivotal role in electing Donald Trump President in 2016. Many communities are thriving anew, capitalizing on unique place-based assets and quality of life. Being wired to the world with high speed internet is an important enabler of this rebirth.

As detailed in the pre-pandemic Chicago Council on Global Affairs report A Vital Midwest: The Path to New Prosperity we see many examples already of smaller, livable Midwest communities, with less frantic lifestyles and a much lower cost of living, finding new economic vitality past their “farm and factory” roots. They also may be a bit better buffered from things like global pandemics.

Marquette and Traverse City, Michigan; Duluth, Minnesota and Ashtabula, Ohio; thrive anew and attract additional year-round professionals and businesses with their great quality of life along cleaned up Great Lakes waterfronts, and in rebooted historic downtowns.

Columbus, Indiana, and Midland, Michigan prosper as their “company-town” employers—Cummings Engine and Dow—stay on the leading edge of clean energy and water technology innovation; and support a robust and thriving civic, arts, and cultural life.

Decorah Iowa, attracts new residents and visitors as a local food and foodie hub. Brown County, Indiana builds on its history as an arts colony, attracting hundreds of artists as residents and dozens of art galleries, shops, studios, and venues for visitors.

These communities, and many more like them in the Midwest illustrate the economic opportunities when you are connected to the world, and can offer a unique quality of life and place.

But too many Midwestern communities remain “unplugged.” In the 12- state Midwest region, there are 736 counties out of 1041 total counties (70.7%) with a below-average percentage of the population afforded access to broadband. Across all counties, 9,879,000 people in the 12-state region do not have broadband access (a number equivalent to the population of Michigan).

If a national priority were made to provide residents of just the below-average counties broadband, an additional 6,770,000 people would be plugged into the economy. If the below-average counties were just brought up to average (maybe more realistic than 100% broadband access), an additional 4,697,000 would reap the benefits. Or if the effort focused on the nine states in the region that were laggards (NY, PA, and IL are above average), and brought them up to the national average, an additional 3,471,000 people would have broadband access.

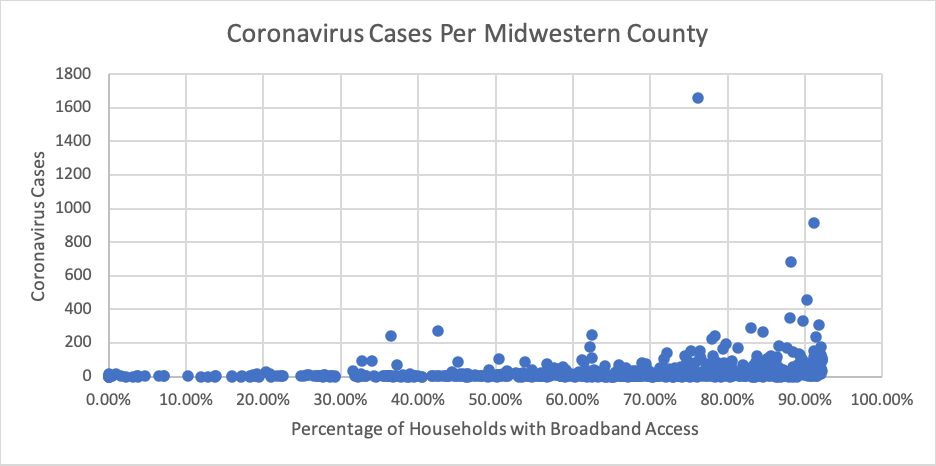

It is also true that our smaller places, including the many that lack good high speed internet access, to date have been buffered a bit from COVID-19, being harder to reach in the first place, with less dense-dwelling populations slowing the virus spread, and providing easier environments in which to stay socially distanced. The figure below illustrates that among Midwestern counties the well “wired” urban centers have the most COVID-19, with “unwired” rural hinterlands and smaller communities relatively unscathed.

The rate of confirmed coronavirus cases per capita is as high as 0.8% in Wayne County, Michigan home to Detroit. Across the 12-state region as a whole, the rate of the coronavirus is 0.41%. Excluding New York State, and its New York City COVID-19 hotspot, just 0.18% of the population has tested positive. And in the counties in the 12-state region that have below-average broadband access that rate is 0.08% (1/10th of Detroit's rate).

So many Midwestern communities already possess place-based assets that can underpin new economic growth. Tangible and intangible attributes like history, culture, charm, and a “know-your-neighbors” sensibility, undergirded by a lower cost and pace of living; stable, less-climate-change-crazed weather and available water, all position many communities for success. Now as folks are going to live a more socially-distanced life-style, and may desire to place health, safety and “de-stressing” life at the fore, the appeal of Midwestern communities may grow for many.

But a precondition for this shift is to provide current residents and newcomers the infrastructures they need to thrive in today’s highly interconnected and interdependent world and economy — an interdependence vividly illustrated by the pandemic’s spread. Extending the essential foundation of high speed internet access to all people and places in the Midwest, and across the nation, will both facilitate an economic recovery, and make our people more confident, comfortable and resilient after the COVID-19 crisis.

Jack Farrell and Courtney Hylant contributed to this article.