Truss' Number Is Up: Brexit And The Delusion Of Dogma

Mayhem in Westminster has roots in Brexit and a political culture that favors dogma over evidence, argues columnist Chris Morris.

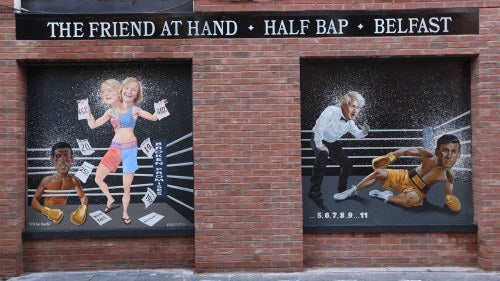

Liz Truss tried to ignore the numbers, but they caught up with her quickly. She lasted less than two months as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom, a new record.

Her first month in office was dominated by state events surrounding the death of the Queen. So, her attempt to run the country, and impose more than £40bn in unfunded tax cuts, was all over in a few short weeks.

She didn’t have the numbers in parliament to get her economic plans up and running. She didn’t have the numbers on paper to convince the markets that she knew what she was doing.

It was a devastating reality check, but it didn’t come as any surprise. The abrupt failure of Trussonomics was the latest manifestation of a dogma of delusion, which has helped frame six years of British political paralysis.

The turning point, and the root of the current crisis, was the decision—made by a narrow majority of British voters—to leave the European Union. Politics has never been quite the same again, because the form of Brexit pursued by successive Conservative governments wasn’t based on numbers, or data, or hard facts. It was based on slick slogans and big promises no one could keep.

A free trade deal with the United States? That has always been on the back burner, to put it politely.

Lower immigration? Without free movement of people from elsewhere in Europe, there are not enough workers to keep the economy moving.

Take back control? The financial markets have just reminded the UK–in brutal fashion– that sovereignty is a complex notion in an inter-dependent world.

But some of those who fought and won the Brexit referendum in 2016 became convinced that they could persuade voters of almost anything, as long as they were prepared to keep repeating it often enough.

A few months after the referendum, after 25 years as a foreign correspondent for the BBC, I was posted back to a small island trapped in political turmoil. It was bitterly divided, friends and family were falling out, the atmosphere was febrile.

Coming home was a rude awakening, because Brexit Britain was a world of mysteries. It wasn’t foreign any more, but it might as well have been. There was talk of traitors, and nooses outside parliament; judges were condemned as enemies of the people; you were either with us or against us.

It was all a little disconcerting.

At the end of a long day reporting on an earthquake or a revolution on the other side of the world, thoughts of the green fields of England had always been rather reassuring.

Well, the fields were still green and the trains still ran on… (actually let’s not mention the trains)—but suddenly everyone was angry. The country, we were told, had had enough of experts. The will of the people would prevail. The will of some of them, at least.

And what did those people want? A hard border and free trade for starters, never mind that those two political promises pushed in different directions. The vast majority of economists, including those who worked inside government, were making the obvious point that putting up trade barriers and cutting ties with your closest neighbors would not make you richer. But voters had been promised riches, so the economic evidence was set aside. It became a hallmark of post-Brexit politics that if the facts didn’t fit, you could ignore them.

And as Donald Trump was rising to power in the United States, so too was Boris Johnson, the star of the Leave campaign, in the UK. The two men are very different, but they are both populists driven by a powerful political instinct: that the story is more important than the detail; that slogans have more impact than statistics.

The story that Johnson and his party were determined to tell was that Brexit would usher in a new golden age. So it was that over the course of several years, two elections, three (soon to be four) prime ministers and six finance ministers, the government assured us that everything was going to be brilliant.

But the numbers still didn’t add up. Disputes in Northern Ireland didn’t go away. Trade and investment fell. Despite constant rallying cries from Johnson, you really can’t have your cake and eat it. Unfortunately, Truss’s economic plan was based on the belief that you can. She promised to cut taxes and protect public services, without a mandate from the electorate, in an economy which had shrunk.

Part of the drive to get the UK out of the European Union came from a well organized group of libertarian ultras. They dreamed for years of turning Britain into a low-tax regulation-slashing Singapore-on-Thames that would once again rule the waves.

And when Truss and her short-lived government took power, so did they. Fully intending to ignore the cautious warnings of those who put more faith in data than dogma, the revolutionaries were installed in Downing Street. But their ideas failed to survive their first encounter with reality.

Britain’s economic woes, of course, are not all down to Brexit, and it would be foolish to suggest that they are. These are challenging times. The unprecedented COVID-19 pandemic has been followed by Russia’s brutal war in Ukraine, creating difficult economic circumstances across the world. But Britain over the last six years has been something else. And Britain over the last six weeks has been something else again. Brexit, and the delusions it created, has been a damaging force multiplier.

Promises have been made that couldn’t be kept. There has been more heat than light, and lots of shouting. Evidence-based politics has been in short supply.

Whatever your views on Brexit, there were viable routes out of the European Union, which would have done less economic damage. But the Conservative government didn’t take any of them. As a consequence, the country remains divided, it has become poorer, and it is still searching for a new place in the world.

Looking at the UK from further afield, there is a temptation to watch in horror, pass the popcorn, and raise a knowing eyebrow. After all, the Brits have always been good at comedy, haven’t they?

But the fallout from the UK’s crisis of governance matters, because it is partly about the durability of western democratic systems, and what happens when politics is not based on evidence, or rooted in reality. As Russia commits atrocities in Ukraine, and the Chinese communist party rubberstamps the leadership of Xi Jinping, the challenges are very clear.

The world’s leading democracies need to draw strength from each other, but there is no guarantee that the drama in London is coming to an end. The economic ideologues who helped Liz Truss into power are heading back to their think tanks. But the instability of the last six years remains baked into the system.

Boris Johnson, a political chameleon who has never let the facts stand in his way, has already had a short-lived flirtation with the idea of making a dramatic comeback. He was kicked out of office by his own party earlier this year, after one indiscretion too many. But he’s a great survivor, to whom many Conservatives are unwaveringly loyal, and the delusionist-in-chief will continue to cast a long shadow.

Whatever happens, Brexit won’t be reversed, at least not any time soon. The opposition Labour party, bruised by the battering it took when it tried to oppose the politics of delusion, doesn’t want to talk about it. And why would the EU want to take the risk of readmitting such an unpredictable partner?

After the chaos of the last few weeks, though, the Conservatives are more unpopular than at any time since modern polling began. Those are numbers that not even this government can ignore. But it may take a general election to restore some semblance of sanity.