Chicago and Its Mexican Immigrants—a Need Like No Other

More than any other large American city, Chicago has depended on immigrants to offset the sluggish growth of its native-born population. The decline in immigration will destabilize Chicago's population.

Chicago's Decline in Immigration

More than any other large American city, Chicago has depended on immigrants, particularly Mexican immigrants, to offset the sluggish growth of its native-born population. Yet the emergence of a new trend—negative net migration from Mexico—now threatens the city's demographic vibrancy. Between 2009 and 2014, more Mexicans left than entered the United States. As shrinking cities aren't vibrant cities, Chicago will need to look at new ways to boost its population in the future.

Shifting Demographics

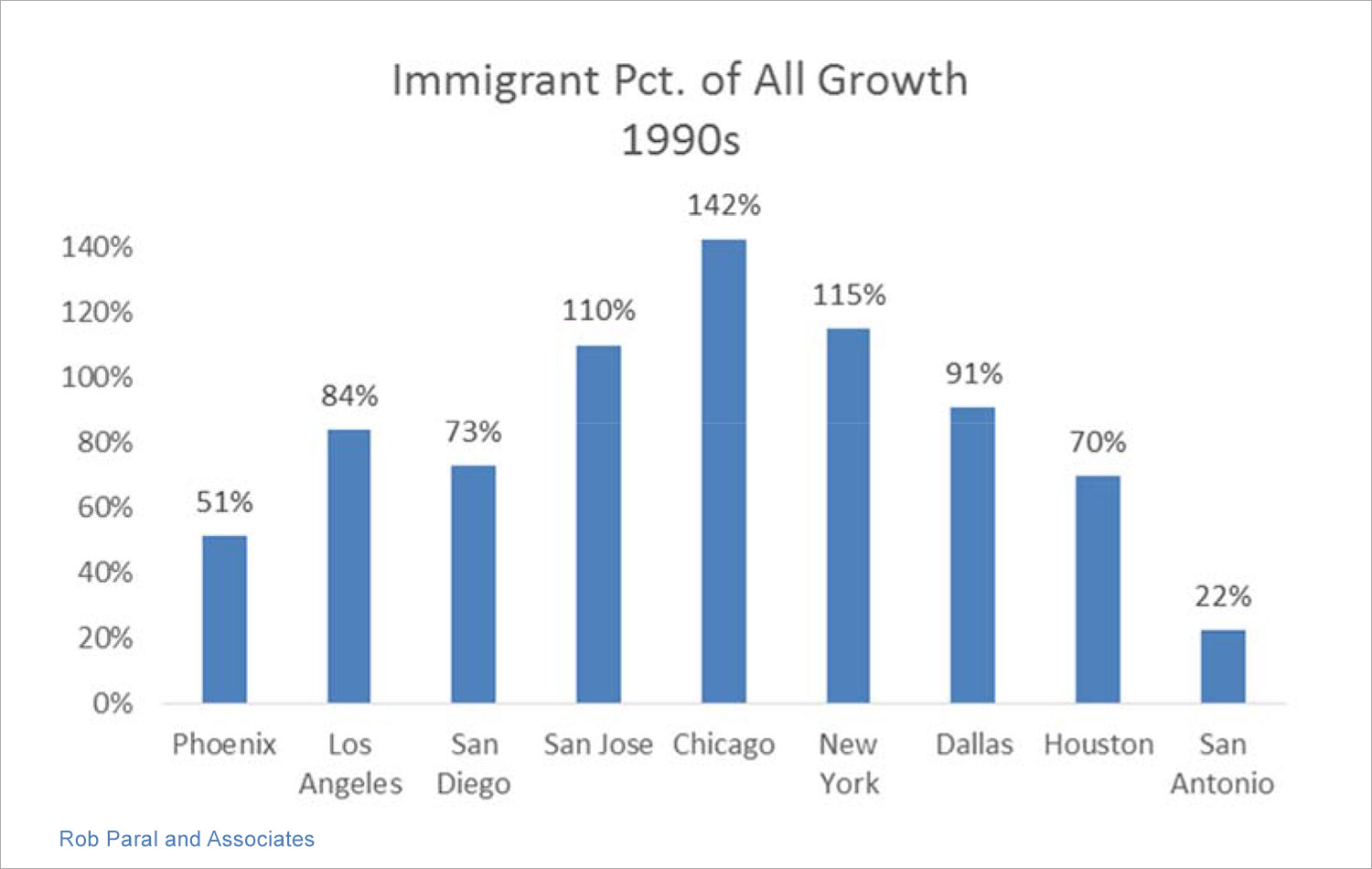

Throughout the 1990s, immigration accounted for all of Chicago's population growth. The increase in immigrants represented 142 percent of Chicago's growth in that decade, meaning that immigration offset native decline. The city overall grew by 112,000 people: The native-born population fell by 47,000 as foreign-born rose by 160,000. No other large city had close to a similar dynamic.

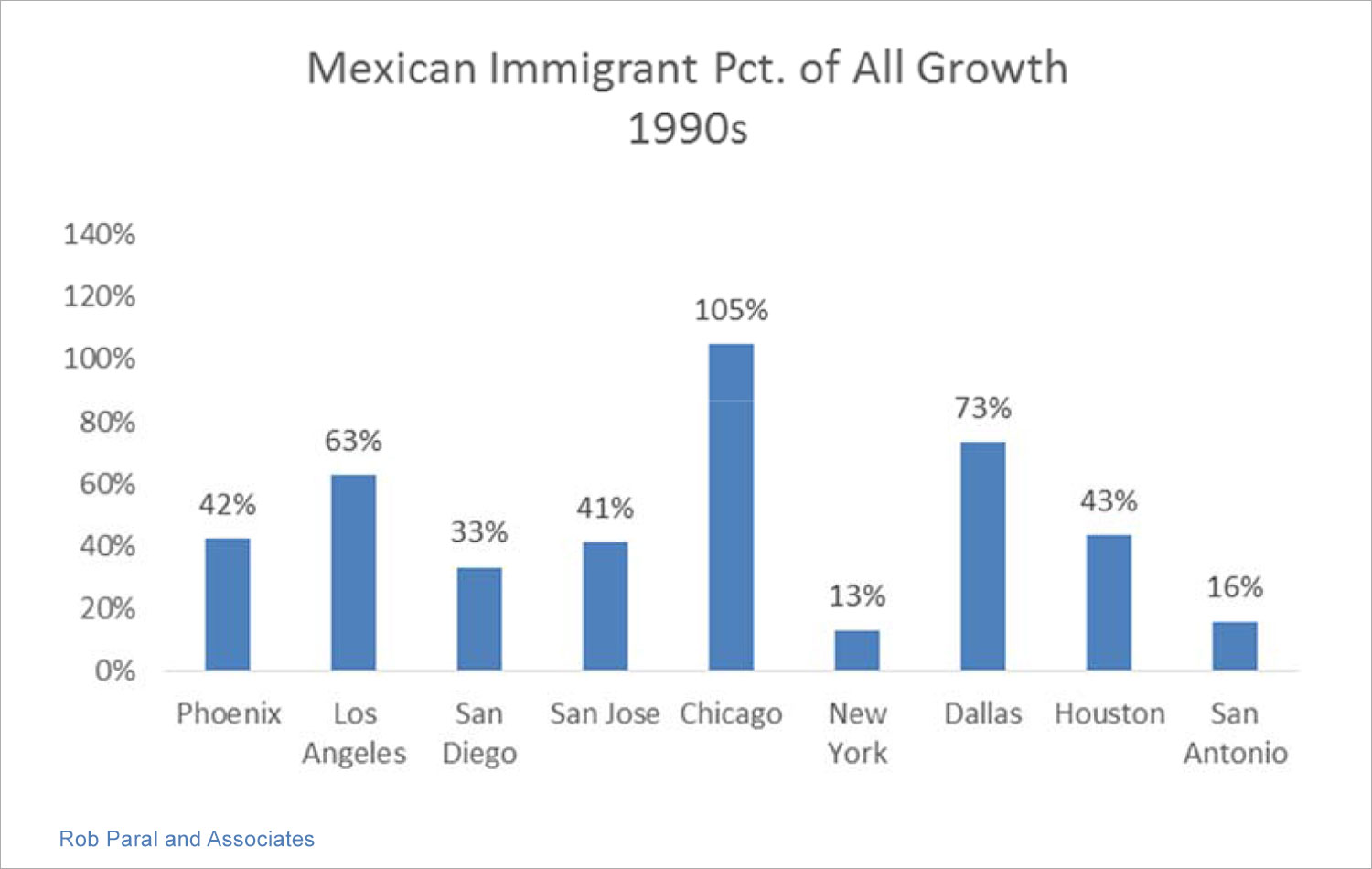

For Chicago, immigration from Mexico was especially important during the 1990s. The number of Mexican immigrants rose by 117,000—105 percent of all growth—in Chicago in that decade.

Similar trends played out at a national level until 2007, at which point undocumented immigration from Mexico peaked and then began to decline. Given the importance of Mexican immigration to Chicago, it is useful to examine population change before and after this 2007 shift.

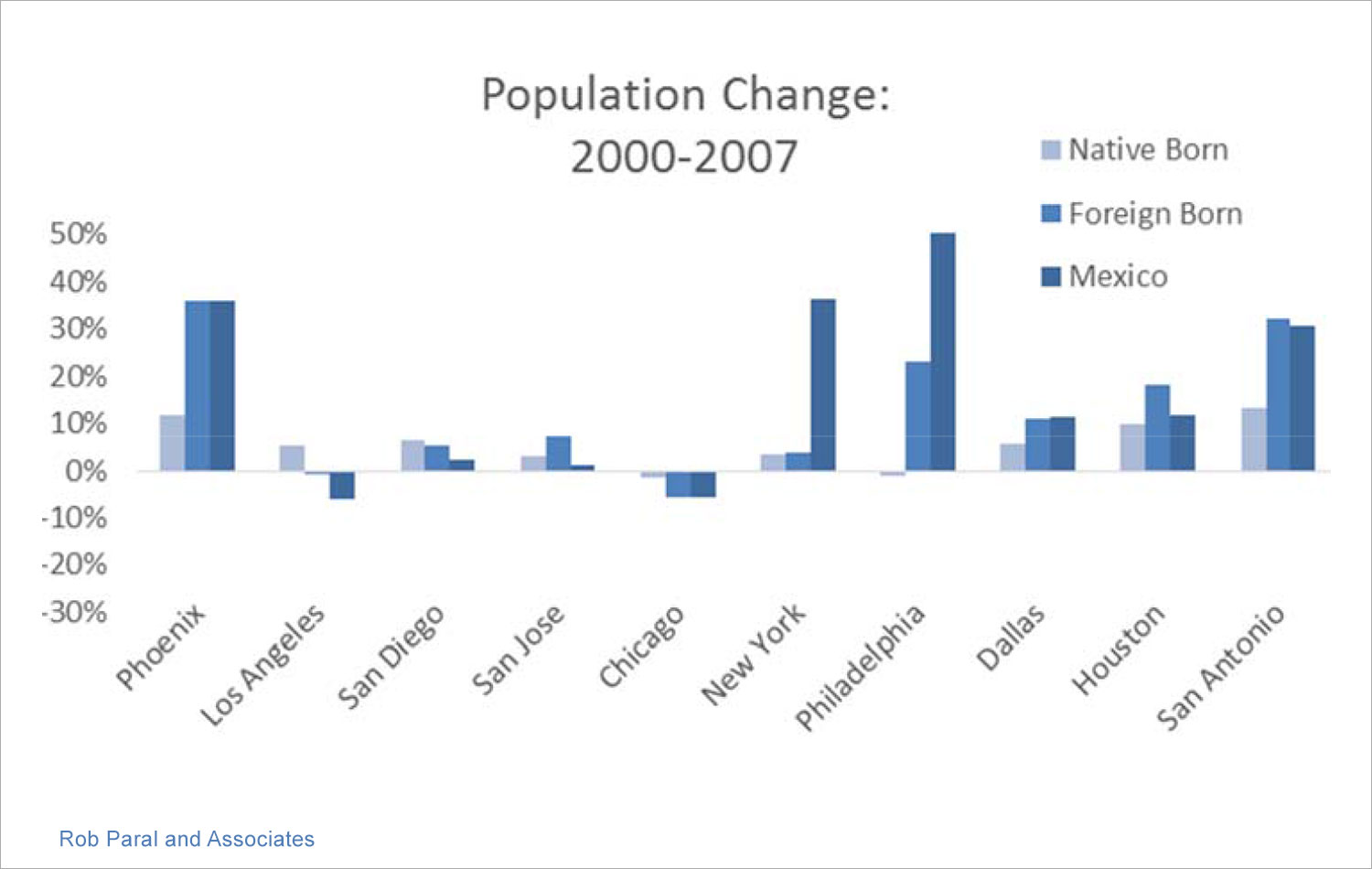

Beginning in 2000, Chicago's overall population began to fall, the effect of not only a declining native-born population (as was the case in the 1990s) but also a drop in the overall immigrant—and specifically, Mexican immigrant—population. Chicago was alone among the ten largest cities to have all three populations diminish between 2000 and 2007. Only Los Angeles had a comparable decline in Mexican population, while Philadelphia saw a decline in its native-born numbers.

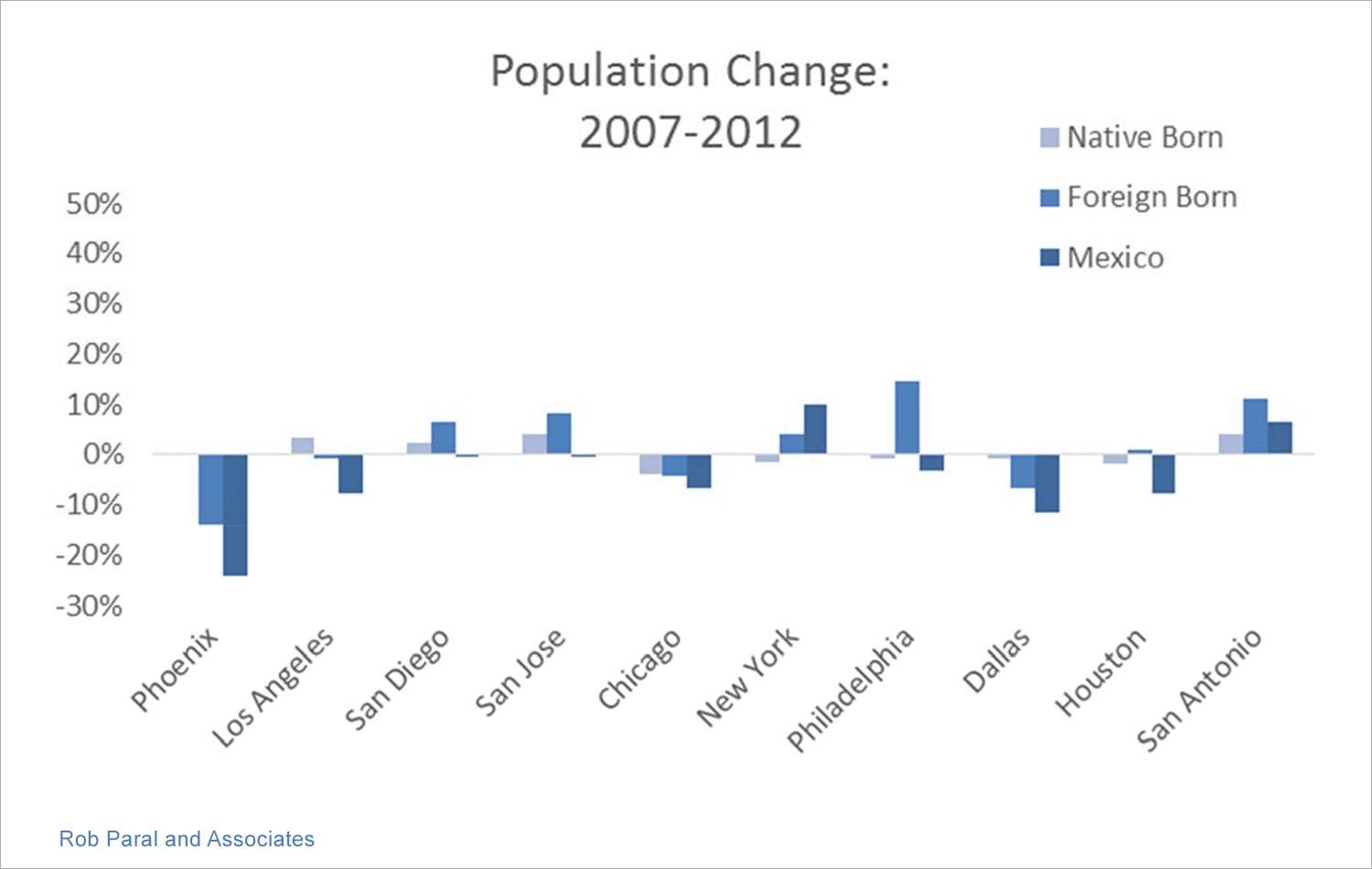

After 2007, falling Mexican-born populations became a reality in eight of the 10 largest cities. Loss of Mexican immigrants slowed down the overall foreign-born growth trends in Phoenix, Los Angeles, Chicago and Dallas, but in most large cities the native population grew. Only Chicago and Dallas had declines among both immigrants and natives—and Phoenix eked out a 0. 3 percent growth among its native born.

Changing Chicago Neighborhoods

Today, how are these trends playing out in Chicago? Demographics are changing in the city's Mexican immigrant neighborhoods for two reasons. First, the lack of new immigration from Mexico contributes to neighborhood population loss because new arrivals do not replace other persons who move away or die. Second, the overall population in these communities is likely older today than it was in previous decades. Some of Chicago's Mexican immigrant neighborhoods have been receiving immigrants for fifty years. The earlier arrivals are now in their retirement years. A 25-year-old immigrant who arrived in the mid-1960s is now in his or her mid-seventies. Their children may have moved away and a spouse may have passed away.

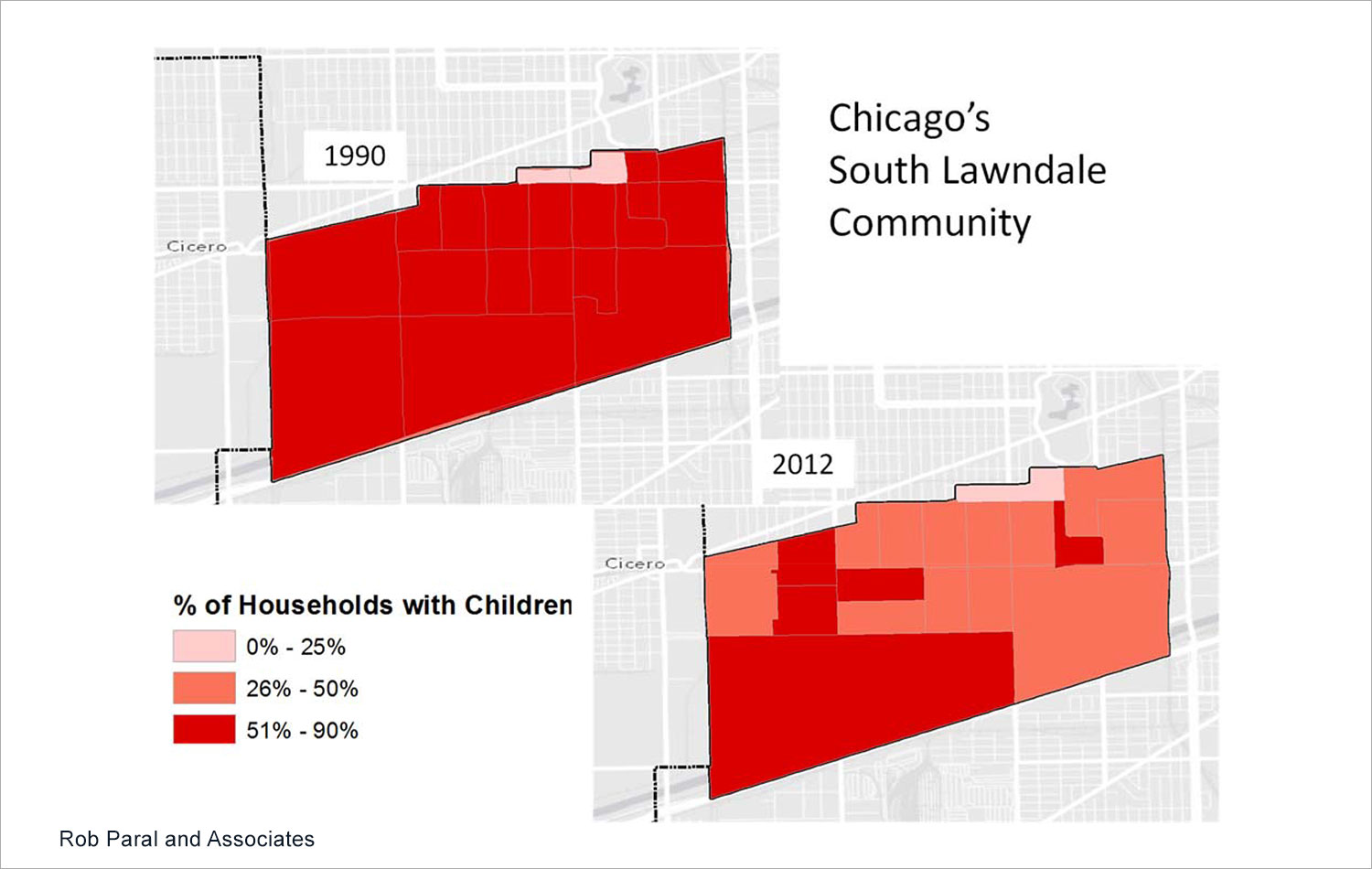

Dual trends of diminished immigration and overall aging of immigrant populations can be seen in Chicago's South Lawndale neighborhood. Located southwest of the Loop, the area has been an immigrant settlement area for over a century, having earlier been home to European immigrants.

South Lawndale, which today is 85 percent Latino, lost 10 percent of its population between 2000 and 2010. The community overall is also getting older. In 1990 more than half of households across South Lawndale had children, but by 2012 most households did not.

The trend of aging amongst Chicago's Mexican immigrants includes the undocumented population. The last large-scale legalization program for undocumented immigrants, created by the Immigration Reform and Control Act of 1986, had a cut-off date of January 1982. Unauthorized immigrants who arrived after that date were not eligible to get legal status. Thus the typical undocumented Mexican immigrant who arrived in Chicago during the mid-1980s in his or her mid-20s is still undocumented and is now in his or her late 50s.

Local Implications

More than other cities, Chicago in the recent past has relied on immigration and especially Mexican immigration to replace its declining native-born population. Given that the majority of Mexican immigrants, and especially the arrivals of recent decades, have been undocumented, it may be said that more than any large city in America, Chicago has depended until recently on undocumented immigration, from Mexico, to stabilize its population. The recent dramatic drops in immigration from Mexico will likely equate to declines in Chicago's population.

In the absence of Mexican undocumented immigration, the future is not bright for Chicago's population stability or growth. No other group seems likely to replace the Mexican immigration stream and indeed, the African American population of the city is in sharp decline.

While population increase is usually seen as desirable, there may be some benefits to Chicago from the aging of its population and slowing of its growth. Older residents don't require local government expenditures in K-12 education, and the costs of income and health support for the elderly are mainly born by state and federal, not local, governments. Indeed, much of the population—including older Mexican immigrants—may be in their prime tax-paying years. The majority of Mexican immigrants are still of working age, though the lack of new arrivals may be a problem for employers in need of young workers.