After decades of steady progress, the number of people without access to electricity increased in 2022.

That’s according to the International Energy Agency (IEA), which found that 80% of people worldwide who don’t have electricity live in sub-Saharan Africa. In Chad and the Central African Republic, only about 1 in 20 have access to electricity.

Achieving universal access to energy by 2030 is one of the U.N.’s 17 Sustainable Development Goals. Is it possible to provide electricity to nearly three-quarters of a billion people without substantially increasing emissions and exacerbating climate change?

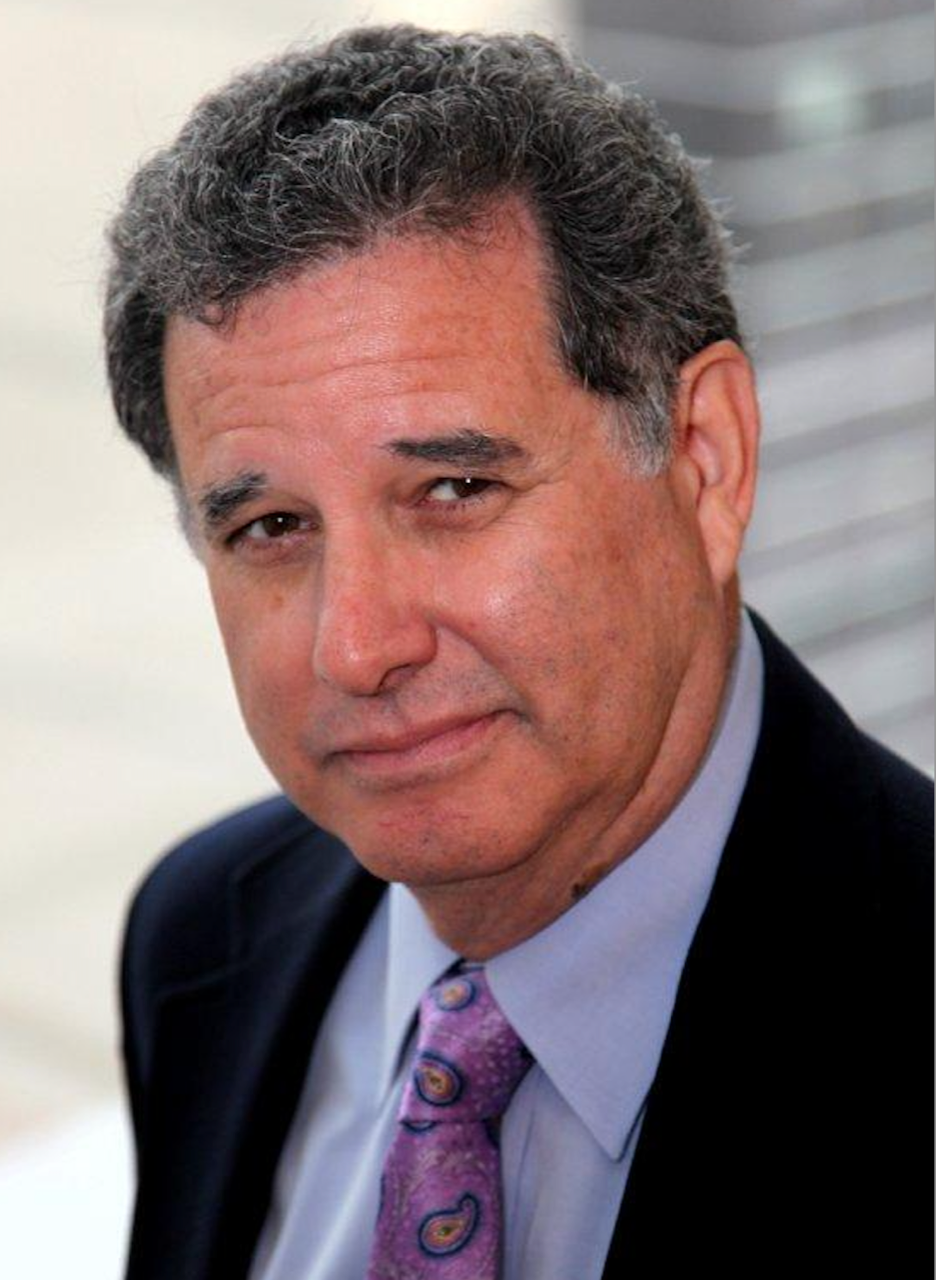

Blue Marble spoke with Gianluca Tonolo, who helps lead the IEA’s Modern Energy Outlook team. Part of his job is developing forecasts to determine how energy access could impact climate emissions.

“All our scenarios that achieve global climate goals – even net zero emissions by 2050 – includes the achievement of universal access to electricity and clean cooking,” Tonolo told Blue Marble.

Expanding electrification “will not undermine climate goals,” he said.

Adding 750 million electricity consumers could actually reduce emissions.

A jolt for rural economies

Electrification can improve people’s health and stimulate the local economy. But poverty is the chief obstacle — even more so than access to the grid.

Recent crises, including the pandemic and Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine, have made affording electricity even more difficult, according to the IEA. Both sparked economic crises that increased costs and disrupted energy supply chains.

Without electricity, rural communities are locked out of the modern economy. Families rely on candles, kerosene stoves, or open fires — even though smoke fumes harm children’s health, Tonolo explained. And when it’s dark, students often can’t study at night and shops have to close at sunset.

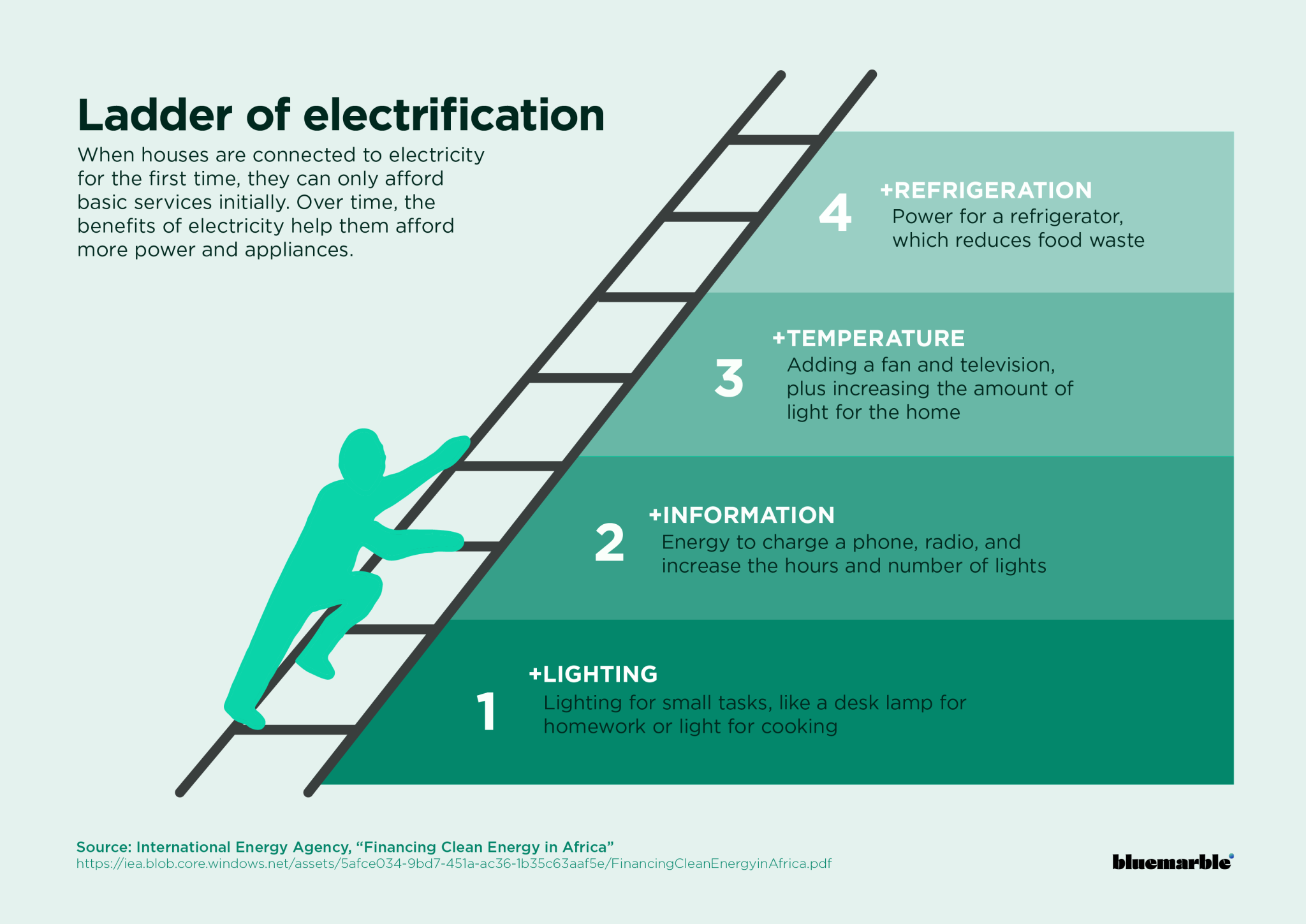

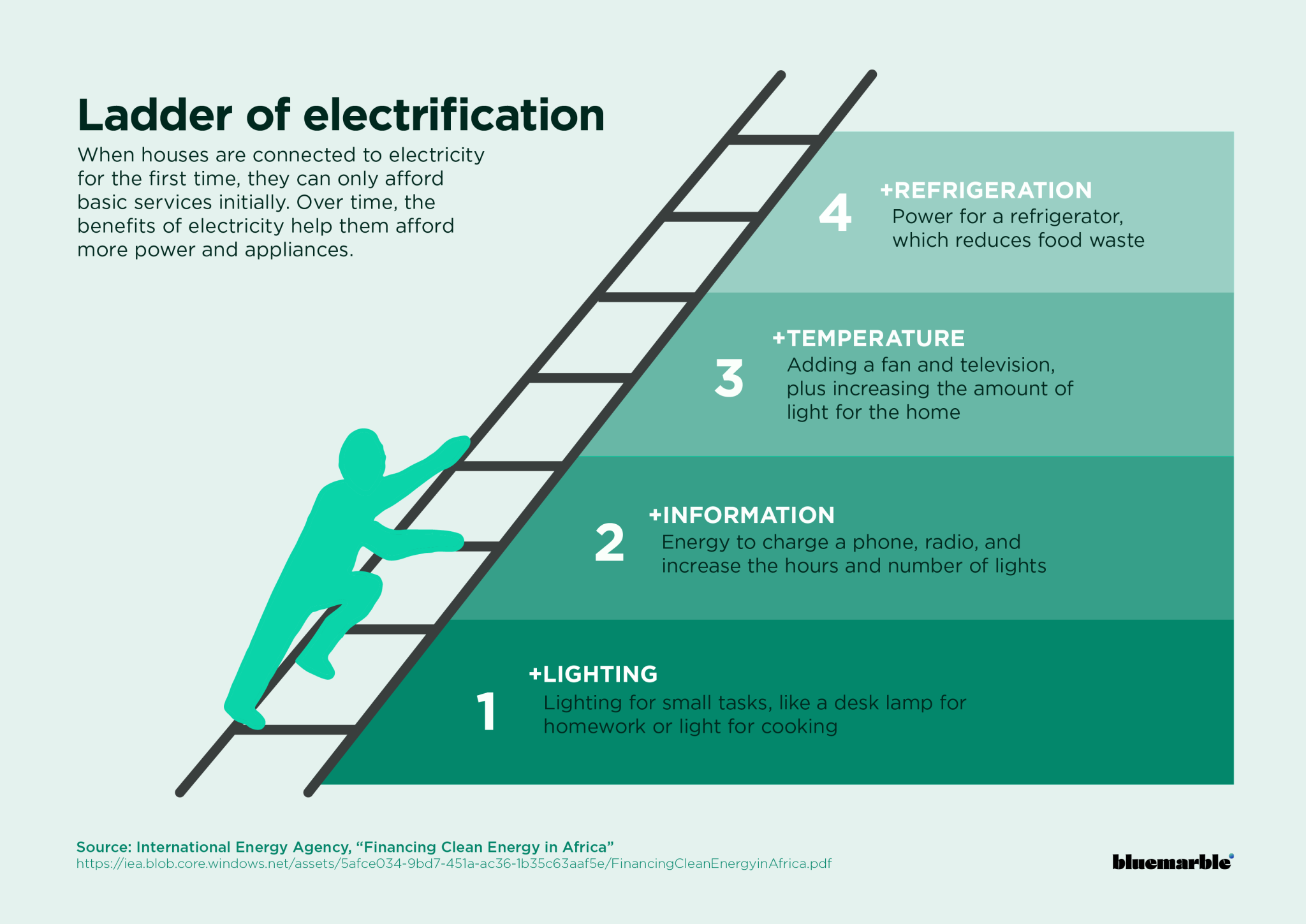

Tonolo also describes electrification as a ladder. The first step for a newly electrified community is typically adding simple lighting, maybe for just two hours a day. A few lamps for a few hours each day can start to change the picture: Children can study after school, shops can stay open longer and earn more money, which in turn stimulates the local economy.

Next, households might buy a radio or a phone and charger. Consumers climb up the ladder and start buying higher energy services: a refrigerator to reduce food waste; a fan to stay cool in the heat; and maybe a television.

But here’s the problem: Even if 600 million people in sub-Saharan Africa without access to electricity were connected to the grid for free tomorrow, half of them wouldn’t be able to afford enough electricity to power a few lights, a phone charger, and a small radio.

On the ladder’s second rung, only 5% would be able to afford powering a fan, a TV, and a few more light bulbs. The next step up includes running a refrigerator, but almost none of the 600 million people would be able to pay their electric bill.

“They cannot afford the electricity that’s on the other end,” Tonolo said.

Expanding energy access could reduce emissions

The lack of electricity isn’t just holding back rural economies. It could also be contributing to climate change.

To be clear, developing countries are responsible for a tiny percentage of global emissions, even though they often bear the brunt of its impacts. Still, expanding energy access and electrification could lead to big net reductions in emissions.

When households rely on open fires and charcoal to cook, they emit lots of methane and chop down trees for firewood, contributing to deforestation. Tonolo’s team found that switching to electricity or even using liquified petroleum gas would reduce carbon emissions by 1.5 gigatons by 2030. That’s roughly the same amount of CO2 emitted by planes and ships in 2022 combined.

In addition, rural communities are often using green technology to expand electricity access. Solar-powered “mini-grids” can’t reach very far. They only cover a few households or businesses, but these standalone systems can provide clean energy for households and essential services in remote locations.

Household appliances that use electricity also are much more efficient than they used to be. In addition to reducing emissions, more efficient appliances means that smaller solar panels become more viable solutions for rural communities trying to expand access. It also becomes cheaper to use electricity each month, too.

“Greenhouse gas emissions savings completely compensate and go beyond the additional emissions from access to electricity,” Tonolo said.

The IEA estimates that it would take about $25 billion each year to provide universal access to modern energy. That’s about 1% of global investment in the energy sector, including both renewable energy and fossil fuels.

“What we are spending for extracting oil, producing electricity, doing all these things… what if we spend 1 percent more? We can electrify all people — 750 million today — that don’t have access to electricity in the world.”

Correction: An earlier version of this story incorrectly described the International Energy Agency (IEA) as part of the United Nations.