German public opinion on Israel-Palestinian conflict shifts after Hamas attack, new polling shows

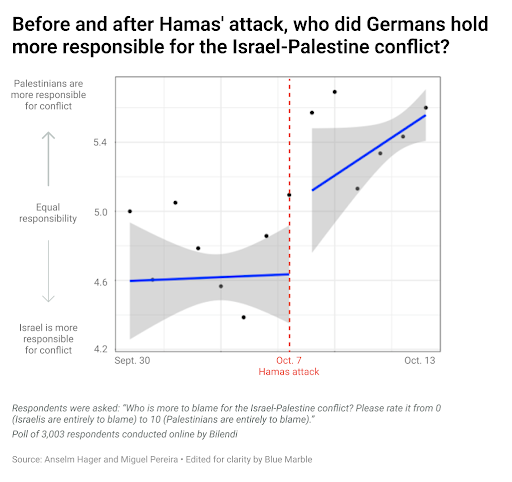

Before Hamas attacked Israel on Oct. 7, killing 1,400 people, most Germans thought Israelis were slightly more responsible than Palestinians for the conflict between them. But new polling shows that the recent violence has changed public opinion in Germany.

The survey of over 3,000 people was conducted both before and during Hamas’ attacks and Israel’s ongoing bombing campaign in the Gaza Strip, and captured Germans’ attitudes changing in real time as the violence unfolded.

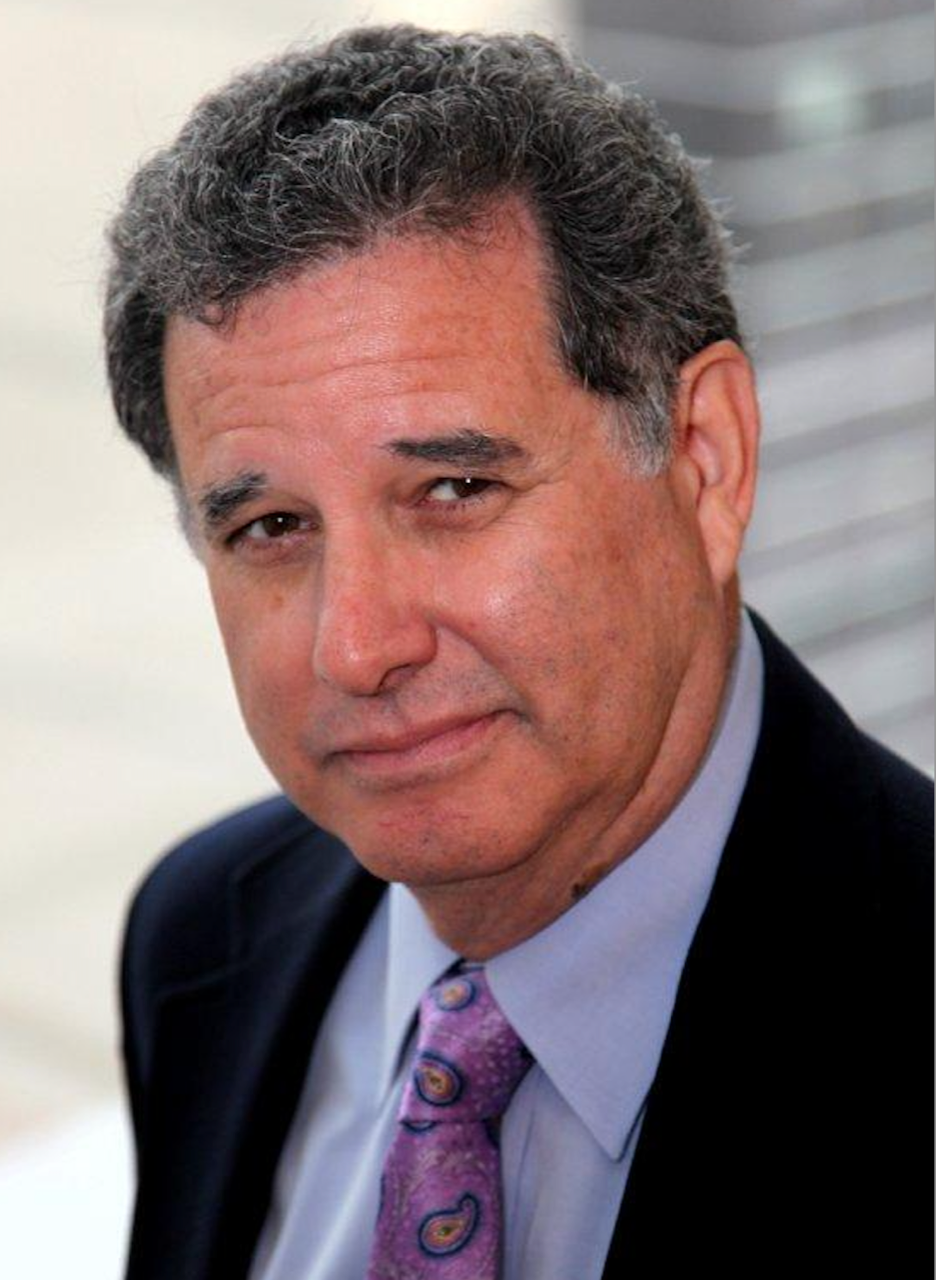

“Just completely randomly, that survey coincided with the recent Hamas attack,” said Anselm Hager, a political scientist and Humboldt University professor who conducted the online poll. He and his co-author, Miguel Pereira, were surveying German attitudes on antisemitism at the time, including a question asking respondents to rank on a 10-point scale: “Who do you think is more to blame for the Israel-Palestine conflict?” where a zero indicated that “Israelis are entirely to blame,” a five indicated that both sides were equally responsible, and a 10 indicated that “Palestinians are entirely to blame.”

Hager told Blue Marble that the data has not yet been peer-reviewed and to not overinterpret the results. But he and Pereira decided to share their findings on X (formerly Twitter) to help audiences understand how public opinion was changing in “a chaotic situation,” Hager said.

Recent polling shows a snapshot of public sentiment in Germany from before the latest Israel-Hamas war. Polling from YouGov this summer found that 17% of Germans sympathized more with the ”Israeli side” and 15% sympathized more with the “Palestinian side.” Twenty-six percent sympathized with “both sides” equally while nearly half (43%) was unsure.

Last year, polling from an independent German research group found that about one-third of Germans agreed that “what the state of Israel is doing to the Palestinians today is in principle no different than what the Nazis in the Third Reich did to the Jews.” Forty percent disagreed and one-quarter said they did not know.

In Hager’s survey, just before the Oct. 7 attack, Germans said Israelis were slightly more responsible for conflict with Palestinians – scoring 4.5 on the 10-point scale.

There was a one-point jump immediately after the attack — to about 5.5 — meaning the German public thought Palestinians were slightly more responsible.

Hager said that people’s attitudes toward the Israeli-Palestinian conflict are usually “fairly stable” and would be hard to change.

“So a one-point jump — that’s a lot,” Hager said.

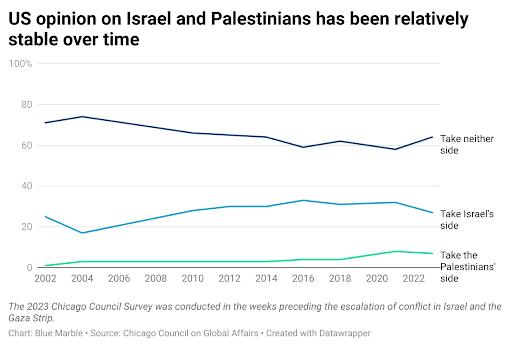

That’s also true in the U.S., where polling over two decades from the Chicago Council on Global Affairs has found little change in support for Israel and Palestinians over time.

“Few people say it’s entirely Israel, it’s entirely Palestine,” Hager said.

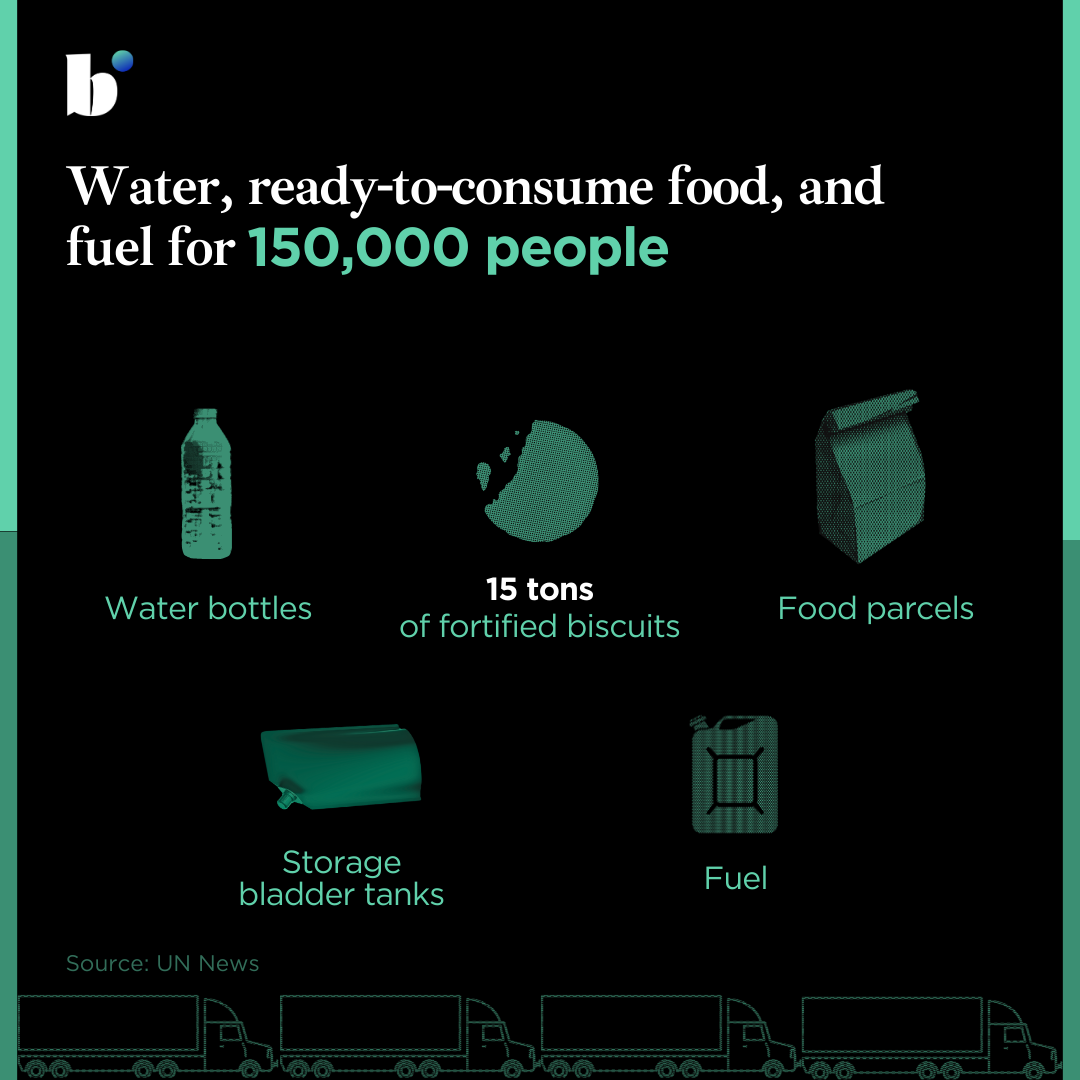

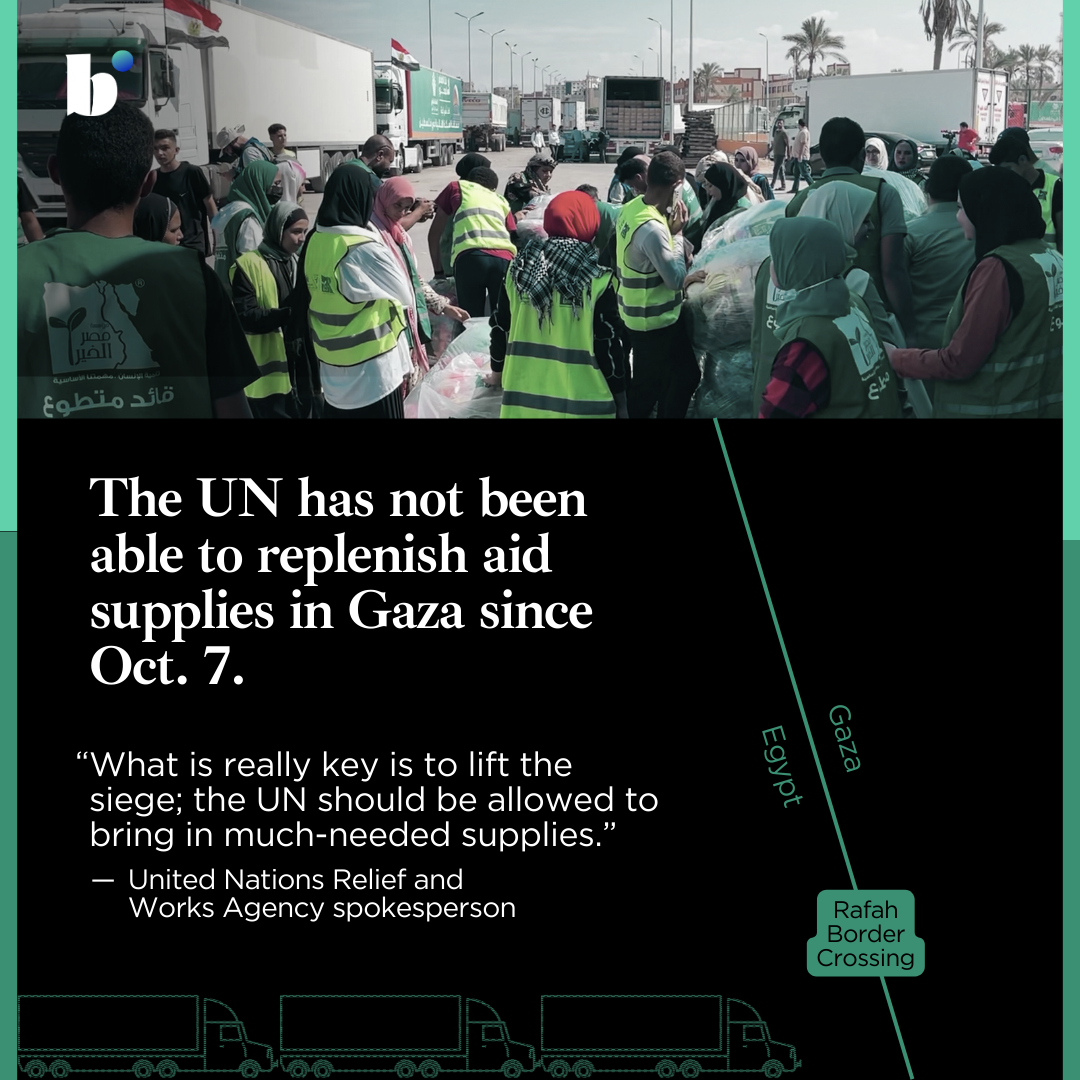

In response to the Oct. 7 attack, Israel declared war on Hamas and dropped at least 6,000 bombs on Gaza, killing thousands of residents.

During Israel’s bombing campaign, German public opinion blaming Palestinians for conflict continued to harden among Germans aged 24 and over.

“If anything, the effect is stronger now,” said Hager.

Attitudes shifted most among left-leaning Germans and older Germans, but the opinions of younger respondents aged 18-24 did not change: They continue to hold Israelis slightly more responsible than Palestinians. Among Germans over age 24 however, public opinion continued trending toward blaming Palestinians even as Israel escalated its bombing campaign in Gaza after Hamas’ attack.

Overall, Hager’s research has found that when German politicians see polling, they change their rhetoric to match public opinion.

“Politicians listen to the polls,” Hager said.

Lama El Baz contributed to reporting and data analysis for this story.

Your tax-deductible donation enables us to break down the most complex global issues so you have the info you need to build a better world.