Human Rights in Retreat? Kenneth Roth Weighs In

Play Podcast

Play Podcast

About the Episode

Human Rights Day lands as conflict is rising and accountability is fading. Big-power tensions are shaking old norms, and new technologies are changing the rules. So, are human rights in retreat—or is this just a familiar cycle? Kenneth Roth, former head of Human Rights Watch, helps us make sense of it.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

Leslie Vinjamuri: Human rights. They're under pressure like never before from Gaza to Sudan to Ukraine. Conflicts are escalating. Undermining the norms that human rights advocates have worked decades to consolidate. Great power rivalries are testing the system with impunity rising, and international accountability breaking down, artificial intelligence and new technologies are changing the rules, sometimes making violations easier, sometimes making them harder to hide.

So what's really happening? Are human rights actually in retreat, or is this a cycle that we've seen before, and who or what can actually push back?

Few have seen it up close like Kenneth Roth, legendary human rights advocate and former executive director of Human Rights Watch.

Kenneth Roth: …Every government has to at least pretend to respect human rights.

LV: Here's his take. Decades on the front lines have given him a front row seat to what drives progress and what threatens it. And today he's sharing it with us.

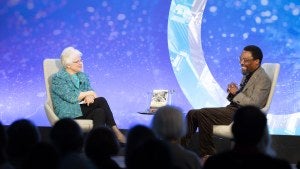

I'm Leslie Vinjamuri, president and CEO of the Chicago Council on Global Affairs, and welcome to Deep Dish.

You led one of the most influential organizations in the world, in the human rights sector, that was constantly presumably trying to think creatively about how to use your leverage. As an organization and in your own role because of your status in the field to influence governments to do the right thing: what did you try, what failed abysmally, and what worked?

KR: The premise of the work of Human Rights Watch, and really the broader human rights movement, is that in today's world every government has to at least pretend to respect human rights. Now we know they fall short, but this pretense is a critical aspect of their legitimacy.

It's a way of saying we government officials are looking out for you, the people, rather than just ourselves and our cronies and our Swiss bank accounts. When Human Rights Watch enters a country, when we investigate and document the embarrassing discrepancy between this haughty pretense and the often ugly reality, that discrepancy is shameful.

And governments attack us, they hate it. They will say we were biased or deceived or misunderstood, but we're super careful, and we win those battles. Ultimately, the government recognizes that they're not able to get rid of the bad press until they change the bad conduct.

LV: What does that mean? You say you win the battles, but surely you haven't won every time.

KR: In the sense of the reputational battles, we actually do.

When I left Human Rights Watch three years ago, we were getting about a thousand media mentions every single day. We were able to shine a very intense spotlight on governmental misconduct. They may deny it, but after a while, we have the facts. We don't publish until we know that we're right.

For example, in Eastern Democratic Republic of Congo, 12 years ago or so, Human Rights Watch was addressing the fact that the Rwandan government was supporting a rebel group known as the M23 that was raping and killing its way through the countryside. We put out a report, and Paul Kagame, the Rwandan president, denied it. He said, no, you're wrong. A few months later, we put out another report showing that Rwanda was still doing it, and he lied again. It wasn't until the third report that everybody recognized that Human Rights Watch was telling the truth that Kagame was lying through his teeth. At that stage, we were able to get US Secretary of State John Kerry and British Foreign Secretary William Hague to call Kagame and say, if you want your age to continue, you've got to stop supporting the M23.

The M23 crumbled within days. It actually disappeared for about eight years. It's now back because Kagame has spent the interim trying to make himself better able to defend against these kinds of sanctions. I think also, frankly, the West's view of Kagame has become more accepting of his brutal dictatorship.

But it shows that, at least in this era, we were able to stop the M23 from preying upon the people of Eastern Congo for a solid eight years. Which is something. It's not putting an end to it altogether, but it shows that with these kinds of battles about the facts, we win. Governments that lie, we can show that they're lying, and ultimately, there really is a reputational cost to that, which we can then try to couple with the fact that every government wants something from the international community. If we can try to deprive their access to things like armed sales or military aid, preferential trade benefits, or invitations to fancy summits. That's another way of putting diplomatic and economic pressure on governments to change their behavior.

LV: I was thinking back to you and your leadership period. I just chaired a panel on a book that's come out on reflecting on the 1990s. People think about the 1990s as the heyday of liberalization, the opening up of the former Soviet countries' democracy, and human rights. But you entered the year of the Battle of Mogadishu, the year before the genocide in Rwanda, two years before the murder of 8,000 men and boys in Srebrenica. There was a very dark side of the 1990s. You're then there through the Global War on Terror that followed the US invasion of Afghanistan, Iraq, and the aftermath of the 9/11 attacks. You're there during the Syrian civil war and the election of President Trump, not once, but twice.

You were also there for the majority of what are now 19 cumulative years of democratic backsliding. Give us a sense of where we are now relative to all these other moments. Are we in a fundamentally different place, or has it always been tough?

KR: I would say that we are not in a dark place, but as you suggest in your introduction, these things tend to be cyclical. I've seen the ups and downs. I started doing human rights work in the midst of the Cold War, where the fight against communism was deemed to justify backing for highly abusive right-wing military regimes around the world. Then, communism fell. There was this brief moment of euphoria, and suddenly it seemed like the world was falling apart with ethnic cleansing and ethnic conflict in places like Rwanda, in the former Yugoslavia. There was a gradual period where things seemed to be getting better. Trade was paralleling the growth of democracy. But then came 9/11, and suddenly the fight against terrorism justified all kinds of atrocities, systematic torture, disappearances, and endless detention in Guantanamo.

We got past that, but we've now entered the second Trump era. This one is clearly much worse than the first, where Trump is largely removing the US as a proponent of human rights and democracy. He really seems to favor autocrats, at least friendly autocrats. So, it's a challenging moment, but I actually am not depressed, partly because I recognize that these things are cyclical, but also because even when I look at Trump, I think he's malleable. He has his weaknesses that can be played to.

When I look at the world, there's a sort of gradual decline of democracy, but I actually see a reaffirmation of democracy in many parts of the world, particularly outside the established democracies. We're in this ironic moment where there's a real contrast between the West and the rest. People outside the West are more willing to embrace democracy than these days, at least some elements within the West. It's a complicated situation as it always is, but there's a lot to work with. One thing I try to get at in the book I recently published is that there are always ways you can put pressure on governments to force them to behave better. They can be reputational, they can be trying to deprive them of things they want from the international community, but there's always something. Part of what keeps me going is recognizing that these tools work and that governments are rational actors. They have a cost-benefit analysis behind their repression. If we can shift that, we can make things better.

LV: When you’re trying to influence the heavyweight in the room, how do you persuade your own government? To get them on the right side of the challenge?

KR: A good illustration of the difficulty of what you're describing is how we stopped the Bush administration's torture. It wasn't an overnight phenomenon at all. It involved gradually revealing what was happening.

It involved disclosing the location of the secret CIA detention centers where people were being disappeared and tortured. It required a lot of argument because although the Bush administration denied that it was torturing, it really was kind of nodding and blinking to that one. It was in essence saying, we need to be doing this to people, but we're not going to call it torture—even though everybody knows it is, because this is what we need to make us safe. A lot of Americans bought that at first until they came to recognize that the torture was actually the terrorist recruiters’ best friend. Once somebody is tortured, they're ripe to join the Jihadists. Their family members are ripe to do that. This loses the moral high ground that the United States had after the 9/11 attacks. It took a while, and ironically, it was the Abu grave disclosures cases of torture that were not the sort of systematic professional practices being engaged in by the CIA, but completely rookie juvenile stuff being done by low-level soldiers. When people saw the pictures of that, they were appalled.

That was the beginning of the end. The whole thing gradually shut down. We had to do something similar with Guantanamo, where at first it was deemed tough to put people in Guantanamo and to deny them regular trials in federal court to go with these cheap, concocted, on-the-run military commissions until people gradually came to recognize that these military commissions were so fraught with problems. They were designed really to avoid any revelation of the torture, so that they were not convicting anybody. We still have the primary 9/11 suspects, more than 20 years later, never having been tried, and probably never will be tried because the Bush administration refused to put them in federal court. Obama, much to his discredit, didn't do that either.

These are examples where you can't call these complete victories. It took some time, but yes, the US could be moved as you marshal public opinion to recognize that what the government was doing was illegal. It was wrong, and it wasn't even helpful.

LV: I appreciate that you've reminded us that it wasn't just President Bush, but it was also President Obama who took a decision pretty early on that the right thing to do, in his view, for America at that moment in time, was not to pursue the former administration for the question of accountability for torture.

We move now into a different era. We've had a first Trump administration, and we've had a second Trump administration. It doesn’t seem to be an administration that is putting human rights advocacy on the front of the agenda, nor democracy promotion, nor giving priority to working with democracies. If it happens to be that way, perhaps that's okay, but not as a criterion, is it? Fundamentally different than the other very dark moments and things that the US has supported or engaged in, like creating legal forms of torture.

KR: I think there is a difference between the first and the second Trump administrations in that the first time, other governments really stepped in and filled the void. Created by Trump's utter withdrawal from the defense of human rights. Now, there still are things that can be done. With Trump, even if you approach him in a direct manner and say, “You're not respecting human rights.” He'll kind of look at you and say, “Well, what are those?” This is the guy who's bombing and summarily executing supposed drug boats in the Caribbean. We have no idea who's in these boats. But in any event, they should be arrested, not summarily executed. He has no natural sympathy for human rights, but he does have self-regard. Trump is all about himself, and that gives us an opportunity because when he thinks of himself most favorably is, in terms, a master negotiator. This is the guy who can pull off the art of any deal. He's clearly vying for a Nobel Peace Prize. That gives us an opening because you don't get a Nobel Peace Prize for ethnic-like cleansing in Gaza. You don't get a Nobel Peace Prize by turning Ukraine into a Kremlin vassal state. We also, in a sense, can point out how Trump is being bamboozled by the likes of Netanyahu or Putin; that he's a naive negotiator, not a savvy negotiator.

These are the kinds of portrayals in the media that Trump is attentive to. He is a media hound, and while it may be a little bit harder to get it into the far-right media that he favors, he's not oblivious by any means to mainstream media. He spends a lot of time talking to regular journalists. He knows what the mainstream media says about him. He's watching, and he's reading the pulse. The polls show that even his Christian Evangelical base is upset by the genocide that Israel has committed in Gaza. He may not instinctively care that much about human rights, but he cares about himself, and there's no avoiding the fact that the public cares about human rights. If he steps too far outside of the public mainstream, he pays a reputational price that even Donald Trump doesn't like.

LV: I think there are some instances where President Trump has, and correct me if your interpretation is different, but where he actually has felt something. I would take us to the moment when there was the use of chemical weapons during the first Trump administration in Syria. What we were told was that he saw the images, and that's when he decided on a limited strike with very little impact. The war continued. He wasn't willing to do anything more systematic or use more leverage, but the story that we were told in the papers was that he was impacted by what he was seeing.

KR: He clearly was affected by seeing children starve in Gaza. It's not as if he's harmless. The Syria chemical weapons case that you note, a lot of that was about contrasting himself with Obama, because Obama had presided over a huge sarin attack that killed well over a thousand. That was the famous case where he contemplated military action and then backed off. That said, the threat of military action actually did get the Assad government to claim that it was relinquishing its chemical weapons. So, Obama accomplished a lot. Now, under Trump, what he responded to was the use of chlorine, not sarin. He did bomb a few sites, but the Assad government literally breathed a sigh of relief because it was such a token strike that it didn't make any difference at all. There was no behavioral response, but Trump was able to say, “I was tougher than Obama.”

LV: As we know in our Western capitalist societies, there's nothing like competition to spur some productive action.

KR: It’s probably also why I just think that Trump's self-regard does give us leverage. He wants to be better than everybody else, and so we can show that he's failing and that helps nudge him in the right direction for the wrong reasons, but nonetheless in the right direction.

LV: Good outcomes or good outcomes. In previous times, Europe was more productive, had stronger growth, was able to deliver more to its people, and so resisting and standing up had arguably less of an impact. Now, they're on the receiving end of not only the war, but the consequences of potentially Trump linking the economic lever of tariffs to the security questions. And they're doing all of this when they're facing very difficult economic situations at home.

I think Human Rights Watch, it's fair to say, has been primarily focused on political and civil rights. But isn't it the case that if you cannot deliver the standard of living, the economic and social right to your people, mostly in wealthy economies that are struggling in Europe, that the real game we need to fight and play for is development? The human rights industry articulates that as economic and social rights. I think most people, on the receiving end of poverty, extreme poverty, would say it's just about eating, sleeping, and having some medicine. It's a development in a humanitarian issue. Yet the focus, as I see it, for much of the highly visible end of the human rights industry in the West has really been about political and civil. How did you reconcile that with the broader problem of human development?

KR: First, let me say that Human Rights Watch actually does a lot of work on economic and social rights. But on your development point, if I could separate that from what's happening in Europe—because I think you're right to note that Europe has a productivity problem. Its economies are not growing. There's this famous Draghi report that outlines all these remedies that have not been taken, so Europe has its problems. I think that the real issue facing Europe today, which is not dissimilar from that facing the United States, is the rise of the far right, and what that represents is people actually not starving.

You can't say that they're deprived of economic and social rights in at least a basic sense. But they are stagnating. They feel that they're going nowhere, that there's growing inequality around them. And most importantly, the government doesn't listen to them. It doesn't serve them, and it doesn't even respect them. These are the people who are ripe for the appeal of the autocrat. That explains a lot of Trump's success in this country. That's Nigel Farage and his reform movement. In the UK, that's the FD in Germany, that's Marine Lapin and her party in France. The real challenge for the established democracies as a whole is to do a better job of serving everybody, not to be seen as serving just the people who are living in the big connected global cities. They're fine, but the working-class people who are outside of the big cities feel that their life is not improving. Democracies are not doing a great job of appealing to them. It's not so much a development issue as it is one of responsiveness to basic needs in the established democracies.

To put this in perspective, though, it's striking to me that if you look at the rest of the world, it's pretty clear that people who live under autocracies want out. They want a democracy.

I mean, why were Hong Kong's freedoms crushed? Because in 2019 and 2020, hundreds of thousands of people took to the street and said they don't want the dictatorship of the Chinese Communist Party. They want real democracy. And Xi Jinping couldn't contain that because he pretended that the Chinese people liked the dictatorship because it made their lives economically better. The people of Hong Kong had a very different idea, so he had to snuff them out. You can find something similar in a range of other countries, sometimes successfully. In recent years, we've seen huge protest movements, oust autocrats such as Sheikh Hasina in Bangladesh, the Rajapaksa in Sri Lanka. We saw a movement stop a presidential self-coup attempt in South Korea. We saw electoral success against autocrats in Brazil, in Poland. Most recently, we've seen governments that start shooting at protestors, being ousted in Nepal and Mozambique. So these are the good positive developments. On the flip side, there are some governments that are just so brutally repressive. That they stifled the protests. That's what happened in Iran with the Women Life Freedom movement. That's what happened with Putin in Russia. It's not like these popular movements always win, but what they show is that the people who have had to live under a government that is unaccountable to them—they don't want that government, they want democracy. There's this ironic contrast right now between the established democracies who haven't really firsthand experienced autocracy and are souring on democracy. They're more willing to continence an autocratic alternative, and everybody else who knows what that's like and doesn't want it.

LV: Although we know there's a range, right? Because in Hong Kong, they had something, but they lost it. That's different for most people. Prospect theory tells us that's different than people being lifted out of extreme poverty in daily life, which feels like safe, prosperous, somewhat dynamic question marks about where China's going. But there's a range on that big question of autocracy.

KR: Even on China, it’s impossible to know. Some very clever polling that has been done in a way that people can answer honestly, without realizing that they're revealing anything, shows huge discontent with the government. The so-called Blank Paper Protests, when many young people came out to protest against the Zero COVID lockdowns, which they saw as callous and harming people. They would stand there with blank paper. The point was to say, I don't need to write anything on this piece of paper because you know what I'm going to say. These were very clever, hugely successful. And Xi Jinping stopped Zero COVID immediately. They were utterly successful protests, so I just think we don't know. We're seeing various ways the Chinese people express themselves in terms of this lying flat phenomenon. A lot of people are just dropping out. You see many young people not wanting to have children because they have no faith in the future. There are a lot of bad signs. Coming on top of the fact that, because of poor policy making by the Communist Party in the past, such as the one-child policy, which has led to a huge demographic crisis today. Even Xi Jinping's prioritization of certain high-tech industries at the expense of basic social safety nets so that so many people have to save for their retirement.

Rather than providing the consumer spending that most feel the Chinese economy needs to really break through the middle-class barrier. So, you know, there are problems there, and the fact that yes, of course the government has brought many people out of poverty, much of the poverty that it created with the great leap forward in the Cultural Revolution. That progress seems to be rapidly slowing in the midst of economic mismanagement today.

LV: You said the word “technology.” We are in a period of phenomenally rapid and very high-stakes technological change with artificial intelligence. How do you conceive of, from a human rights perspective, the challenge and opportunity of artificial intelligence?

KR: I think that the evolution of the human rights movement can be understood in terms of the progress of communications, through technology. Because back in the day, when information traveled by steamship, you could only learn about big, long-lasting problems. You couldn't even pretend to affect something that was happening. Now that gradually changed, particularly with the emergence of email, it was greatly accelerated with the emergence of social media. Today, we can learn about things and disseminate things, and that provides great power for the human rights movement.

Now the difficulty, of course, is that the bad guys have these same tools. It used to be that they would have to contend with real journalists and real editors before spouting their propaganda. Today, they just use artificial-intelligence-enhanced bots to spread their garbage on social media. And a lot of people don't know the difference.

LV: It is mostly bad guys, let's be fair. I was going to correct you, but you know, the reality is with a few exceptions.

KR: Most people who have certain decencies to them are committed to the truth, and it's the people who are trying various nefarious schemes who try to propagate their lies. Now, what leaves me some hope is, ironically, the behavior of Vladimir Putin and Xi Jinping because each of them oversees a huge propaganda apparatus. They have everything under the sun to spread their disinformation, but they don't trust that to be enough to persuade their people. They recognize that their people are still going to seek out the truth. So they also maintain this fast censorship machinery because they want to block people who try to evade the disinformation and get at the truth. That, to me, speaks to the ongoing power of the truth and the importance of established, decent, respected institutions—whether media or civil society—to continue doing what they're doing. Because the information that is truth-based remains very powerful in forcing governments to change.

LV: Kenneth Roth, thank you so much for joining us.

KR: My pleasure. Thanks for having me.

LV: And thank you for listening to this episode of Deep Dish on Global Affairs. I'm your host, Leslie Vinjamuri. Talk to you next week.

Deep Dish is a production of the Chicago Council on Global Affairs. If you enjoyed today's episode, make sure to follow Deep Dish on Global Affairs wherever you get your podcasts. And if someone you know might find it interesting, send it their way.

As a reminder, the opinions you heard belonged to the people who expressed them, and not to the Chicago Council on Global Affairs. This episode is produced by Tria Raimundo and Jessica Brzeski, with support from Marty O'Connell and Lizzie Sokolich. Thank you for listening.

Human Rights

Human Rights