Abstract

Several empirical measures of congressional voting prove that partisanship has reached new heights at some point during the past 5 years. Public opinion surveys can help to show whether this political division has seeped into the public zeitgeist. While Republicans and Democrats generally agree on the general outlines and goals of US foreign policy, in recent years their longstanding differences on the importance of working within a multilateral framework and the threats posed by immigration and climate change have accelerated. There are also new cracks in previously shared opinion toward China, Russia, and Israel. And recent polls show that assessments of the US administration’s handling of the coronavirus outbreak also breaks along partisan lines. The outcome of the 2020 election is not likely to help bridge these divides nor neutralize the risks of continuing polarization.

Similar content being viewed by others

New highs in polarization on Capitol Hill

After the 6 January mob storming of the US Capitol and Donald Trump’s announcement that he would not attend Joseph R. Biden Jr.’s upcoming inauguration, several commentators made parallels of the current political situation with the extreme political divisiveness of the 1860s. ‘Not since the dark days of the Civil War and its aftermath has Washington seen a day quite like Wednesday,’ wrote Peter Baker (2021) in the New York times on 13 January, the day that Donald Trump was impeached for an unprecedented second time and just a week after the January assault.

Even before January 6, however, several empirical measures revealed that polarization in Congress had reached levels not seen since the end of Reconstruction. The Philadelphia Federal Reserve publishes an annual Partisan Conflict Index going all the way back to 1891. This measure tracks the frequency of newspaper articles reporting partisan disagreement among politicians at the federal level. By this measure, partisan conflict hiked up to new levels during the Obama and Trump administrations. Another model, the Congressional Roll-Call Votes Database is based on legislators’ roll call voting records. These results also show that polarization reached apex levels at some point in the past decade, exceeding that in 1879.

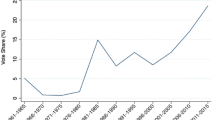

While not as longitudinal a measure as the Partisan Conflict Index or the Congressional Roll-Call Database, Congressional Quarterly measures party unity scores going back to 1956. This is the degree to which members of Congress align with their parties on votes in which a majority of Democrats opposed a majority of Republicans. Initially recorded around 70% in 1956, party unity decreased to record lows in the House and for Senate Republicans in 1970; for Senate Democrats in 1968. Party unity voting rather steadily climbed after that, with the highest scores ever recorded for House and Senate Republicans in 2016–2017; Senate Democrats reached a new party unity high in 2013.

These empirical tools help to describe partisan conflict on Capitol Hill, while public opinion surveys can help demonstrate the impact of this political division on the public zeitgeist.

Public opinion and the influence of partisan messaging

Partisanship is a powerful shortcut that individuals use to filter and shape their opinions (Hurwitz and Peffley 1987). Messages or cues from political leaders, which are then amplified by the media, are a mechanism for individuals to arrive at policy stances. What’s more, studies have shown that these messages influence both domestic and foreign policies (for example, Zaller 1992; Page and Shapiro 1992; Guisinger and Saunders 2017; Lasala Blanco et al. 2020) as well as specific attitudes toward war (Berinsky 2009).

When elites divide along partisan lines, public opinion tends to follow the leaders. In other words, those individuals who affiliate themselves with the Republican party usually follow the policy stances of influential opinion leaders of the same political persuasion; and vice-versa among Democrats (Bullock 2011). Given these results, and the aforementioned growing opposition to policies originating across the aisle in Congress, I expect to find similarly growing divides among the American public on foreign policy attitudes, especially (Druckman et al. 2013) during the Trump era, when congressional polarization reached new highs by previous measures.Footnote 1

For the purposes of this research, I define polarization as substantial differences between self-described Republicans and Democrats on a particular survey result. When possible, I examine partisan divergence, or increasing differences between self-described Republicans and Democrats on a particular issue over time. Polarized responses are often but not always, in opposition to each other (symmetric divergence), which might suggest deepening conflict on an issue (Lasala Blanco et al. 2020). In addition to partisan polarization and foreign policy preferences of the public, the paper also offers some interesting insights into intraparty preference variation within the Republican party during the Trump administration.

First, some areas of foreign policy agreement

The mob that broke into the Capitol seeking to overturn the election outcome was not a representative group of Americans. And while the outcome of the 2020 vote does not tell us whether voters themselves are polarized (Fiorina and Abrams 2008), the fact that 74 million Americans voted for Trump in 2020 compared to Biden’s 81 million votes, signals a large degree of division within the American electorate.

Comprehensive analyses by the Pew Research Center (2017) have shown that partisan differences on domestic issues such as the role of government and racial discrimination have risen over the course of the past two decades. But on foreign policy, the differences are often less clear (Kertzer et al. 2020), likely reflecting a broad consensus on general foreign policy goals among the two parties’ leaders for the past 70 years or so. As noted by Zaller (1992), liberal internationalism has been the ‘mainstream’ policy norm embraced by both parties (with some differences in degree, to be sure) since the 1950s. Even in 1968, with great attention being paid to the Vietnam War, Page and Brody (1927) found that most voters did not choose a candidate based on their position on the war, because the differences between Richard Nixon and Hubert Humphrey were minimal. By the same token, Bryan and Tama (2021, in this edition of International Politics) reveal that bipartisanship is much more common in congressional votes on foreign policy than on domestic issues.

Surveys conducted by the Chicago Council on Global Affairs over the past four decades reveal that the American public seems to have internalized many of these mainstream principles. Majorities of Americans across political affiliations express support for active US engagement in world affair and US security alliances. Bipartisan majorities also support military deterrence by maintaining superior military capabilities and US bases abroad. Since 1998, majorities of Democrats and Republicans have said that globalization is mostly good for the United States, and since 2004, majorities of both party supporters agree that international trade is good for the US economy and US consumers. In this same journal issue, Marshall and Haney (2021) highlight additional areas of the public’s significant support for international engagement.

Differing views on how to engage globally

At the same time, Chicago Council Surveys show that Republicans and Democrats express diverging preferences about the way the United States should engage with other countries. A chief difference is how best to project US influence in the world. Democrats prefer to work in solidarity with the international community and elevate international institutions. Republicans prefer that the United States seek self-reliance in world affairs and maintain the military strength that they believe is needed to deter hard security threats (Smeltz et al. 2020a).

While not necessarily a recent public divide, statements by both candidates in the 2020 presidential election highlight this public opinion difference. In 2019, President Donald Trump articulated a clear message of his America First platform at the 74th United Nations General Assembly, favoring nationalism over multilateralism. He noted that the future belongs not to the ‘globalists’ but to the ‘patriots,’ going on to elaborate: ‘The future belongs to sovereign and independent nations who protect their citizens, respect their neighbors, and honor the differences that make each country special and unique.’

For his part, candidate and now President Biden (2020) stated that his foreign policy would embrace the networks of partnerships and alliances the United States has built over the decades to enhance national security and freedom. ‘Working cooperatively with other nations,’ Biden has argued, will amplify our own strength, extend our presence around the globe, and magnify our impact while sharing global responsibilities with willing partners.’

While the United States has groused about paying its UN dues for several decades, criticism of the UN reached new heights during President Trump’s tenure. Trump and company withdrew US participation from the Human Rights Council, refused to fund Palestinian refugees and got even further behind in its financial contributions. Republican party supporters among the public are not too keen on the United Nations, either. Chicago Council polling shows that since first asked in 2006, a majority Republicans have consistently disagreed with the statement “the United States should be more willing to make decisions within the United Nations even if this means that the United States will sometimes have to go along with a policy that is not its first choice.” Conversely, over the same time period, a majority of Democrats have agreed with the statement; in the 2020 survey, the highest percentage yet of Democrats endorsing this view was recorded (84%). While this partisan difference is longstanding, the divide on this question has increased during the Trump years, and 2020 marks the first time that the partisan gap exceeded 40 percentage points (84% of Democrats agree versus 37% of Republicans). The gap has increased because of roughly similar increases in Democratic support (+ 4) between 2018 and 2019 and decreases among Republicans (-7) in 2020.

Despite favoring US international engagement in general, there is no majority support among Republicans for greater involvement of international institutions. The 2020 Chicago Council Survey shows that only minorities of Republicans say the United Nations (39%), the World Trade Organization (30%), the World Health Organization (32%) or the United States (42%) itself should be more involved in addressing the world’s problems. By contrast, majorities of Democrats think each of these organizations should be more involved (68% UN, 53% WTO, 71% WHO) as well as the United States (69%). The same survey shows that majorities of Democrats say that the United States should more frequently participate in international organizations, sign international agreements, and provide humanitarian aid, while Republicans tend to think the level at which the Trump administration uses these foreign policy tools is sufficient.

More agreement, but some shifts, on allies and NATO

Former President Trump targeted the NATO alliance from the start of his campaign for the presidency, criticizing the alliance as ‘obsolete’ and other NATO countries for ‘not paying their fair share.’ Addressing a crowd in Racine, Wisconsin in 2016, he said that other NATO countries are ‘ripping off the United States,’ that they need to pay their fair share, and ‘if it breaks up NATO, it breaks up NATO.’

While most Republicans among the public still favor the US commitment to NATO, these messages do seem to have had some influence on Republican public opinion. Majorities of both Democrats (85%) and Republicans (60%) say the United States should maintain or increase its commitment to the NATO alliance. But the difference between them is the largest it has been in Chicago Council polling since 1974. The recent drops in Republican commitment to NATO – from 71% in 2019 to 60% in 2020 – could be related to cues from President Trump’s criticisms of NATO allies. At the same time, support for the alliance among the Democratic public has never been higher, also likely a reaction against the Trump messaging, an example of Zaller’s (1992) ‘two message model.’Footnote 2

Republicans may support NATO more than other international organizations because they favor working with allies. A majority (57%) of Republicans are willing to make decisions with US allies even if this means the United States might have to sacrifice its first choice, though Democrats are much more convinced (82%). In addition, GOP supporters might also see NATO as an extension of US military power. Republicans are generally more supportive than Democrats of increases in defense spending, and they consistently endorse the US military keeping an edge internationally.

When first asked in 1998 how important it is for the United States to maintain US military superiority as a foreign policy goal, roughly six in ten Democrats (57%) and Republicans (63%) said maintaining military superiority was very important goal. After 2002, however, partisan divisions grew as Democrats placed less emphasis than Republicans on superior military power. When last asked in 2018, 70% of Republicans compared to 41% of Democrats said it is very important for the United States to maintain US military superiority.Footnote 3 The opinion gap between partisans in 2018 was the widest ever recorded, 29 percentage points.

The results presented thus far demonstrate new increases in the opinion gaps between Republicans and Democrats on working within the United Nations, willingness to maintain the US commitment to NATO, and the importance of military superiority. But these are not new points of disagreement, they just became sharper during the Trump administration. Some of the most striking results in the 2020 data are the partisan divergences on the fundamental question of what potential threats affecting the United States are most critical.

Differing emphases on hard vs. soft security threats

In his book about public opinion and war, Berinsky (2009) notes that public attitudes can be directly influenced by dramatic events such as the September 11 attacks and Pearl Harbor, but it is ‘primarily structured by the ebb and flow of partisan and group-based political conflict.’ He goes on to say that the feelings of threat and fear influence public decisions on international issues, just as they do on domestic policies. Thus, it is critical to identify the top threats and fears among Americans today to determine whether there are differences among partisan groups.

Indeed, the 2020 Chicago Council Survey reveals that Republicans are most concerned about traditional or ‘hard’ security threats affecting the United States, More Republicans say that the development of China as a world power (67%) is a critical threat than any other, followed by international terrorism (62%), domestic violent extremism (60%), and Iran’s nuclear program (54%). A solid majority of Republicans also view large numbers of immigrants and refugees coming into the country as a critical threat (61%).

Public concern over hard security threats have typically overshadowed other types of threats in past Chicago Council Surveys. Certainly, the Trump administration kept these conventional threats – and immigration – at the fore of their strategies. While the GOP did not issue an official presidential campaign platform for 2020, President Trump’s re-election campaign focused on his America First policies: ending US industry reliance on China and protecting US manufacturing, reasserting US sovereignty in world affairs and curbing immigration into the United States. For the most part, these campaign priorities seem pretty aligned with those of the Republican constituency.

In contrast to Republican views on threats, the Democratic public is more focused on global and societal issues. For Democrats, COVID-19 is the top-rated threat facing the country with 87% citing it as a critical threat, compared to about half of Republicans who do the same (48%). Republicans’ lesser concern about the pandemic dovetails with messages from President Trump, who repeatedly downplayed the severity of the virus, often contradicting public health experts’ warnings of a grave threat. Many Republican governors also resisted new measures to stem the spread of the virus compared to their Democratic counterparts.Public opinion reflects this politicization of the pandemic, in the Chicago Council Survey as well as other polls.

Besides focusing on the need to get the pandemic under control, the Biden campaign platform also focused on climate change and green jobs, raising the minimum wage and criminal justice reform. These are also top issues for the Democrats among the public. After the coronavirus, the threats deemed most critical to Democrats are climate change (75%), racial inequality in the United States (73%), economic inequality in the United States (67%), and foreign interference in the US elections (69%). Taken together, this disagreement between partisans on the top threats facing the country makes it seem like Republicans and Democrats are experiencing the world in very different ways.

Partisan gaps on immigration, climate change widen

Several items presented in the 2020 Chicago Council threat battery were asked for the first time (COVID-19, racial inequality, and foreign interference in US elections) and therefore preclude longitudinal comparisons. But it bears pointing out that the partisan gap on the longitudinal results on immigration and climate change, which both have a domestic as well as foreign policy component, have only widened with time.

In 1998, the difference between Republicans and Democrats on whether immigration was a critical threat was a mere 2 percentage points in Chicago Council polls. Polarization on the issue has been steadily rising mostly due to incrementally decreasing alarm expressed by Democrats. Generally speaking, Republican views have stayed the same. But partisan gaps expanded notably during the Trump years. Indeed, the percentage point gap between the two parties’ supporters did not exceed 40% until 2017. In 2020, the Republican-Democrat difference widened to 48 percentage points (it was 59 percentage points in 2019). Other results have shown that the Republican-Democrat gap has grown on whether immigration strengthens the United States, even as both partisans have become more pro-immigrant.

When announcing the US exit from the Paris climate agreement, President Trump stated that he ‘was elected to represent the citizens of Pittsburgh, not Paris.’ It was a good line for some audiences, except in the 2016 election year nearly six in ten Republicans (and 71% of Americans overall) said that the US should participate in the agreement. But more recently the idea of rejoining the Paris agreement had Republicans and Democrats running to opposite corners. A 2019 NPR/PBS News Hour/Marist poll found that eight in ten Democrats (81%) but only two in ten Republicans (18%) said that rejoining the climate accord is a good idea.

Democrats have become more alarmed about climate change since Trump was elected, widening the partisan gap to a whopping 54 percentage points, the largest partisan gap of all the issues in the 2020 survey. While Democrats and Republicans have disagreed on the nature of the threat from climate change since Chicago Council Surveys started asking about it in 2008, it was not until 2017 that the partisan difference exceeded 50 percentage points (in 2019 the difference was 58 percentage points).

New partisan differences on China, Russia and Israel

During his tenure, President Trump reframed the foreign policy debate about China, pursuing a more competitive relationship with Beijing on both economic and security matters. While leaders of the Democratic party criticized Trump’s handling of the US-China relationship, they largely agreed that the US should pursue a harder line on China, although in different ways.

These nuanced divisions at the level of elite discourse are reflected in the public as well. While overall views of China have soured among both Republicans and Democrats, Republicans (67%) are far more likely than Democrats (47%) to name China as a critical threat to the United States (+ 26 Republican increase compared to a + 10 Democratic increase in a January Chicago Council survey). In addition, majorities across party lines believe China is more of a rival than partner to the United States (68% Democrats, 76% Republicans) and an unfair trading partner (67% Democrats, 82% Republicans) (Smeltz and Kafura 2020).

But Republicans and Democrats are at odds when it comes to the best way to deal with China. From 2006 through 2019, majorities of both party supporters felt that it was best to undertake friendly cooperation and engagement with China. But in 2020, Republicans changed their mind. Two in three Republicans now think it is best for the United States to actively work to limit the growth of China’s power (64%, up from 40% in 2019), while Democrats still believe that it is best to cooperate with Beijing (60%, down from 74%).

Russia has become another issue with a domestic component given Russian interference in the 2016 US elections. Even before he was elected president, Donald Trump made ingratiating motions toward Russia President Putin on the campaign trail, including an appeal to Russia to locate Hillary Clinton’s deleted emails. Even after US intelligence agencies concluded that Russia was the culprit behind the 2016 cyberhack and social media disinformation campaign against Hillary Clinton, Trump publicly contradicted the agencies’ findings after a meeting with Putin in Helsinki.

Public opinion surveys in the United States following the reports of Moscow’s election interference in 2016 revealed a new partisan divide on attitudes toward Russia. One Economist/YouGov survey showed supporters of the Republican Party – the party of Reagan and his warnings of an “evil empire” – expressed more favorable ratings of Vladimir Putin than of Barack Obama. Despite the conclusions of US intelligence agencies, Americans do not even agree on whether the Russian government tried to interfere with the 2016 elections (90% of Democrats but only 36% of Republicans said Moscow interfered a great deal or a fair amount in a February 2019 Council survey). From a Chicago Council survey in January 2020, Democrats (67%) said they were more than three times as likely as Republicans (21%) to worry about Russian influence on American elections.

Finally, Donald Trump has gone where no president has gone before in recognizing Jerusalem as Israel’s capital and moving the US embassy to Jerusalem. While both Republicans and Democrats agree that US-Israel relationship is an important one, Republicans are significantly more likely than Democrats to say that the US relationship with Israel strengthens US national security (75% vs. 53% Democrats in a 2019 Chicago Council survey). Further, Republicans have become more one-sided in the Israel-Palestinian conflict. In 2004, two-thirds of Republicans said the US should not take either side in the conflict. Six years later, in 2010, they were divided between taking Israel’s side or no side; by 2016, 57% said they should take Israel’s side (59% in 2018). A majority of Democrats continued to say the US should take neither side (Kafura et al 2018).

Not all Republicans follow Trump’s line

A former top aide to the House Republican leadership told the Financial Times that Donald Trump had released a civil war within the Republican party when he embarked on his campaign for the GOP presidential nomination back in 2016. While the large majority of Republican voters voted for Trump in 2020, the data show that not all Republican supporters express support for Trump’s America First approach. Some Republicans express foreign policy views that are more traditional or establishment than populist.

The 2020 Chicago Council Survey found those who considered themselves ‘strong’ Republicans were more inclined to favor Trump for the presidency (95%) than those who said they were ‘not strong’ Republicans (69%).Footnote 4 Differences between strong and other Republicans are also evident on a wide range of other foreign policy issues, including working within the UN framework, the US commitment to NATO, how best to deal with China, and on the threats posed by COVID-19, climate change, and especially, immigration.

Those who do not consider themselves strong Republicans are also less nationalistic in their foreign policy preferences. They are more likely than strong Republians to favor making decisions, even if it means the United States has to compromise, within the United Nations (49% vs. 28% among strong Republicans) and with allies (62% vs. 53% strong Republicans). They are also more likely to think the US should maintain or increase its commitment to NATO (67% vs. 54% strong Republicans).

Strong Republicans are more likely than other Republicans to be alarmed by hard power threats, while not strong Republicans are more alarmed by COVID-19 (54% consider it a critical threat vs. 43% strong Republicans) and climate change (28% consider it a critical threat vs. 16% strong Republicans). But the largest difference of all is on immigration. While 72% of strong Republicans view immigration as a critical threat, only 47 percent of other Republicans agree.

Finally, strong Republicans are much more insistent on taking a harder line and limiting China’s influence (72% vs. 54% among other Republicans). Those who describe themselves as strong Republicans have more of a stake in taking Israel’s side (64% in 2016) than other Republicans (49%) in the conflict with the Palestinians, though this gap has narrowed significantly since 2010.

Taken together, these differences suggest that while Donald Trump seems to have influenced Republican opinion on foreign policy, there is still a segment within the Republican party that are less inclined toward populist positions and express more traditional Republican stances.

Is bipartisanship a net negative now?

While polarization is a top concern for foreign policy opinion leaders, it polls as only a second-tier concern for the American public (Smeltz et al. 2018). Moreover, a 2019 Battleground Poll found at least 8 in 10 Americans agree that compromise should be a goal for political leaders, but the same proportion said they are tired of leaders compromising their values and want them to stand up to the other side. While Joe Biden emphasized the importance of unity in his inaugural address, the president may not be seen as a unifying figure. Gallup tracking surveys since the 1950s show that the last 15 presidential years account for 14 of the 15 most polarized years comparing presidential approval ratings.

This report attempts to look at whether polarization on foreign policy issues has increased in the past four years, and the results show that it has. On certain measures, such as immigration and climate, the differences between partisans have been increasing incrementally, reaching a high-water mark in 2020.Footnote 5 In other cases, partisan attitudinal gaps of single digits grew to double digits during the Trump years (the threat from China, for example). In others, the gaps exceeded 50% for the first time (the threats perceived from climate change and immigration). The data suggest that most of the shifts examined here have occurred because of changing views among Democrats. In particular, Democrats have become more concerned about climate change and more supportive of the UN in recent years and ever less concerned about maintaining US military power and the threat from immigration. Some of this change may be due to the shifting demographics of the Democratic electorate, and future analyses should drill down on the effects of these variations on polarization. While the demographics of Republican party supporters have undergone less dramatic swings than among Democrats, the shifts in education levels, especially among white voters in both parties, deserve a close examination.

Another area that warrants investigation is the role of the media and information flows on partisan divides, including a survey experiment that tests presidential cues on foreign policy attitudes. This analysis infers that messaging from the Trump White House has had an impact on Republican, especially strong Republican, attitudes toward international issues and a countervailing impact on Democratic attitudes. Some standout examples are the decrease in Republican support for the US commitment to NATO, increase in Republican criticism of China, an increase in Democratic support for working within the UN, and Republicans’ weaker opposition than Democrats to Russian interference in US elections. The Republican public’s disagreement with the US intelligence agencies’ findings on Russian interference is particularly concerning, and on this and other issues, might be linked to the information sources they trust and don’t trust. The same goes for Democratic voters’ information sources. As Shapiro and Bloch-Elkon (2008) state, the media in this newly partisan era can convey ‘different interpretations of which facts are true and important.’

The new partisan cracks on foreign policy issues that had previously elicited bipartisan agreement are particularly concerning. Trump’s all-guns-blazing confrontation with China and denigrating critiques of special counsel Robert Mueller’s Russia investigation likely helped to shape partisan disagreements that are based largely on domestic political concerns. The problem with politicizing these issues is that it shatters a shared consensus on the imminent threats facing the country and the most important priorities for our national security. It has also proven to creates a ripe environment for conspiracy theories and ‘alternative’ facts. In the broader sense, as Schultz (2017) has pointed out, polarization at the leadership level can lead to the failure to learn from foreign policy mistakes, dramatic policy swings that hurt our credibility with allies, and making the political system vulnerable to foreign intervention.

Just as polarization has become the norm on many domestic policies, recent surveys reveal that public opinion on foreign policy is also susceptible to the same path. The increase in division is disconcerting. But these trends should be balanced with the knowledge that Americans across the political spectrum consistently support US engagement in the world and the key pillars of the post-World War II US foreign policy, including alliances, military deterrence and trade. Republicans and Democrats differ in views on the best approaches to deal with the world, but they both agree that they don’t want to retreat from it.

Notes

As James Bryan and Jordan Tama point out in their articles in this volume, these measures may be imprecise because they exclude voice votes and consent votes on foreign and other policies. But they are used here as empirical examples that show consistent patterns across time.

The two-message model in Zaller (1992) would lead to the expectation that a Republican would be pushed in a pro-Trump (or at other times, a conservative) direction by messaging from the White House, while a Democrat would react in the opposite (or a liberal) direction.

In this same issue, Sarah Maxey (2021) references a generally greater inclination among Republicans to support the use of force.

Among those who describe themselves as Republican party supporters, 56 percent said they were strong Republicans and 44 percent said they were not strong Republicans.

At the same time, other Chicago Council and other polls show that despite partisan disagreement on how critical the threat, Americans are able to agree on specific options to address climate change and immigration policy. But getting political leaders to agree on the sequencing of actions (for example immigration enforcement and a pathway to citizenship) or to take action is another matter.

References

Baker, P. 2021. A Preordained Coda to a Presidency, The New York Times, 13 January, https://www.nytimes.com/2021/01/13/us/politics/donald-j-trump-impeachment-second-time.html. Accessed 29 January 2021.

Battleground Poll. 2019. Cited on Georgetown University Institute of Politics and Public Service website, October, https://politics.georgetown.edu/battleground-poll/october-2019/. Accessed 28 January 2021.

Berinsky, A. 2009. In Time of War: Understanding American Public Opinion from World War II to Iraq. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Biden, J. 2020. Why America Must Lead Again: Rescuing U.S. Foreign Policy After Trump. Foreign Affairs, March/April, https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/united-states/2020-01-23/why-america-must-lead-again. Accessed 28 January 2021.

Bryan, J., and J. Tama 2021. The Prevalence of Bipartisanship in US Foreign Policy: An Analysis of Important Congressional Votes. Paper presented at workshop on Domestic Polarization and U.S. Foreing Policy, Heidelberg University, 2020.

Bullock, J. 2011. Elite Influence on Public Opinion in an Informed Electorate. American Political Science Review 105 (3): 496–515.

Druckman, J., E. Peterson, and R. Slothuus. 2013. How Elite Partisan Polarization Affects Public Opinion Formation. American Journal of Political Science 107 (1): 57–59.

Fiorina, M.P., and S.J. Abrams. 2008. Political Polarization in the American Public. Annual Review of Political Science 11 (1): 563–588. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.polisci.11.053106.153836.

Gollwitzer, A., C. Martel, W. Brady, P. Pärnamets, I. Freedman, E. Knowles, and J. Van Bavel. 2020. Partisan differences in physical distancing are linked to health outcomes during the COVID-19 pandemic. Nature Human Behavior. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-020-00977-7.

Guisinger, A., and E. Saunders. 2017. Mapping the Boundaries of Elite Cues: How Elites Shape Mass Opinion across International Issues. International Studies Quarterly 61 (2): 424–441.

Hurwitz, J., and M. Peffley. 1987. How are Foreign Policy Attitudes Structured? A Hierarchical Model. American Political Science Review 81: 1099–1120.

Jaffe, G., and J. Johnson. 2019. In America, talk turns to something not spoken of for 150 years: Civil War. The Washington Post, 2 March, https://www.washingtonpost.com/politics/in-america-talk-turns-to-something-unspoken-for-150-years-civil-war/2019/02/28/b3733af8-3ae4-11e9-a2cd-307b06d0257b_story.html. Accessed 16 November 2020.

Kafura, C., D. Smeltz, and A. Von Borstel. 2018. US Public Divides along Party Lines on Israeli, Palestinian Conflict. The Chicago Council on Global Affairs, 20 November, https://www.thechicagocouncil.org/research/public-opinion-survey/us-public-divides-along-party-lines-israeli-palestinian-conflict. Accessed 29 January 2021.

Kertzer, J., D. Brooks, and S. Brooks. 2020. Do Partisan Types Stop at The Water’s Edge? The Journal of Politics. https://doi.org/10.1086/711408.

Klein, E. 2020. Why We’re Polarized. New York: Simon & Schuster.

Lasala Blanco, M. N., R. Y. Shapiro, and J. Wilke. 2020. The Nature of Partisan Conflict in Public Opinion: Asymmetric or Symmetric? American Politics Research, 1532673X2096102.

Marshall, B., and P. Haney. 2021. The Impact of Party Conflict o Executive Ascendancy and Congressional Abdication in US Foreign Policy. Paper presented at workshop on Domestic Polarization and U.S. Foreign Policy, Heidelberg University, 2020.

Maxey, S. 2021. Finding the Water’s Edge: When Negative Partisanship Influences Foreign Policy Attitudes. International Politics. Paper presented at workshop on Domestic Polarization and U.S. Foreign Policy, Heidelberg University, 2020.

Miller, J. 2019. Party unity on congressional votes takes a dive: CQ Vote Studies. Roll Call, 28 February, https://www.rollcall.com/2019/02/28/party-unity-on-congressional-votes-takes-a-dive-cq-vote-studies/. Accessed 29 January 2021.

Page, B., and R. Brody. 1927. Policy Voting and the Electoral Process: The Vietnam War Issue. The American Political Science Review 66(3): 979–995, cited in Saunders, E. (2016) Will foreign policy be a major issue in the 2016 election? Here’s what we know, The Washington Post, 26 January https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/monkey-cage/wp/2016/01/26/will-foreign-policy-be-a-major-issue-in-the-2016-election-heres-what-we-know/. Accessed February 1, 2021.

Page, B., and R. Shapiro. 1992. The Rational Public: Fifty Years of Trends in Americans’ Policy Preferences. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Partisan Conflict Index. The Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia, https://www.philadelphiafed.org/surveys-and-data/real-time-data-research/partisan-conflict-index. Accessed 29 January 2021.

Pew Research Center. 2017. The Partisan Divide on Political Values Grows Even Wider. October 5, https://www.pewresearch.org/politics/2017/10/05/the-partisan-divide-on-political-values-grows-even-wider/. Accessed 29 January 2021.

Schultz, Kenneth A. 2017. Perils of Polarization for U.S. Foreign Policy. Washington Quarterly 40 (4): 7–28.

Shapiro, R.Y., and Y. Bloch-Elkon. 2008. Do the Facts Speak for Themselves? Partisan Disagreement as A Challenge to Democratic Competence. Critical Review 20 (1–2): 115–139.

Smeltz, D., J. Busby, and J. Tama. 2018. Political polarization the critical threat to US, foreign policy experts say. The Hill, 9 November, https://thehill.com/opinion/national-security/415881-political-polarization-is-the-critical-threat-to-us-foreign-policy. Accessed 28 January 2021.

Smeltz, D., I. Daalder, K. Friedhoff, C. Kafura, and B. Helm. 2020a. Divided We Stand: Democrats and Republicans Diverge on US Foreign Policy. Chicago Council on Global Affairs (Chicago).

Smeltz, D., and C. Kafura. 2020. Do Republicans and Democrats Want a Cold War with China? The Chicago Council on Global Affairs, 13 October, https://www.thechicagocouncil.org/research/public-opinion-survey/do-republicans-and-democrats-want-cold-war-china. Accessed 29 January 2021.

Trump, D. 2019. President Trump United Nations General Assembly Address. https://www.c-span.org/video/?463700-1/president-trump-calls-global-trade-reform-un-speech. Accessed 15 November 2020.

Zaller, J. 1992. The Nature and Origins of Mass Opinion. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

On behalf of all authors, the corresponding author states that there is no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Smeltz, D. Are we drowning at the water’s edge? Foreign policy polarization among the US Public. Int Polit 59, 786–801 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41311-022-00376-x

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41311-022-00376-x